Binoculars for stargazing

Have you been gazing at the night sky for a while now? And are you ready for a view you can’t get with your eyes alone? Before you jump into buying a telescope, try using binoculars. You’ve probably already got a pair lying around your house somewhere. If not, they’re less expensive than a telescope, easier to use and transport to a dark site or use from your yard, and they give you incredible views! Here are our top six tips for binocular stargazers.

1. Binoculars first, telescope later

The fact is that most people who think they want to buy a telescope would be better off using binoculars for a year or so instead. That’s because first-time telescope users often find themselves completely confused – and ultimately put off – by the dual tasks of learning to use a complicated piece of equipment while at the same time learning to navigate the night sky.

Beginning stargazers often find that an ordinary pair of binoculars – available from any discount store – can give them the experience they’re looking for. After all, in astronomy, magnification and light-gathering power let you see more of what’s up there. Even a moderate form of power, like those provided by a pair of 7×50 binoculars, reveals seven times as much information as the unaided eye can see.

You also need to know where to look. Many people start with a planisphere as they begin their journey making friends with the stars.

You can purchase a planisphere at the EarthSky store. Also consider our Astronomy Kit, which has a booklet on what you can see with your binoculars.

2. Start with a small, easy-to-use pair of binoculars

Don’t buy a huge pair of binoculars to start. Unless you mount them on a tripod, they’ll shake and make your view of the heavens wobbly. A pair of 7×50 binoculars are optimum for budding astronomers. You can see a lot, and you can hold them steadily enough that jitters don’t spoil your view of the sky. Plus, they’re very useful for daylight pursuits, like birdwatching. If 7x50s are too big for you – or if you want binoculars for a child – try 7x35s.

Read Sky & Telescope’s article on how to buy your first pair of binoculars.

3. First, view the moon

When you start to stargaze, you’ll want to watch the phase of the moon carefully. But the moon itself is a perfect target for beginning astronomers armed with binoculars. Hint: the best time to observe the moon is in twilight. Then the glare of the moon is not so great, and you’ll see more detail.

Note: The moon is very bright in binoculars. If you want to see deep-sky objects inside our Milky Way galaxy – or outside the galaxy – you’ll want to save your night vision and point your binoculars at the moon last.

Start moon-gazing when the moon is just past new. When it’s a waxing crescent in the western sky after sunset, and you’ll have a beautiful view of earthshine. This eerie glow on the moon’s darkened portion is light reflected from Earth onto the moon’s surface.

Each month, as the moon goes through its regular phases, you can see the line of sunrise and sunset on the moon progress across the moon’s face. That’s the line between the light and dark side of the moon. This line between the day and night sides of the moon is the terminator line. This is the best place to see lunar features casting long shadows in sharp relief.

Check out the gray blotches on the moon – named maria – that early astronomers thought were seas. They’re not seas, of course. They formed 3.5 billion years ago when asteroid-sized rocks hit the moon so hard that lava seeped up through cracks and flooded the impact basins. These lava plains cooled and eventually formed the gray “seas” we see today.

The white highlands are older terrain pockmarked by thousands of craters that formed over the eons. You can see some of the larger craters in binoculars. One of them, Tycho, emanates long white rays for hundreds of miles over the adjacent highlands. This is material kicked out during the Tycho impact about 2.5 million years ago.

4. Then, try a planet

Planets are wanderers. They move around, apart from the fixed stars. You can use our EarthSky visible planets and night sky guide to locate planets visible around the current date. Binoculars will enhance your view of a planet near the moon, or two planets near each other in the twilight sky, for example.

Mercury and Venus. These inner planets orbit the sun inside Earth’s orbit. Therefore, both Mercury and Venus show phases as seen from Earth. Through binoculars, you should be able to see them in a crescent phase before and after conjunction with the sun. Tip: Venus is so bright that its glare will overwhelm the view. Try looking in twilight instead of true darkness.

Mars. The red planet really does look red, and binoculars will intensify the color. Mars also moves rapidly in front of the stars, and it’s fun to aim your binoculars in its direction when it’s passing near another bright star or planet.

Jupiter. Now on to the real action! Jupiter is a great binocular target, even for beginners. Hold those binoculars steady, and you should see four points of light nearby. These are the Galilean satellites: the four moons Italian astronomer Galileo spotted through one of the first telescopes ever made. If you can’t see all four, that’s because they pass in front of and behind the gas giant. Watch how their relative positions change from night to night.

Saturn. Although you need a small telescope to see Saturn’s rings, your binoculars will show Saturn’s beautiful golden color. You may even glimpse Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. Also, good-quality high-powered binoculars – mounted on a tripod – will show you that Saturn is not round. The rings give it an elliptical shape.

Uranus and Neptune. With a finder chart and binoculars, you can spot the two most distant planets. Uranus might look greenish, thanks to methane in the planet’s atmosphere. Once a year, Uranus is borderline bright enough to glimpse with the unaided eye … use binoculars to find it first. Distant Neptune will always look like a star, even though it has an atmosphere practically identical to that of Uranus.

Other solar system objects you might spot with binoculars: the occasional comet (which appears as a fuzzy blob of light) and 12 of the asteroids when they’re at their brightest. Sketch the starfield over subsequent nights to track the star-like asteroid as it moves.

5. Explore inside our Milky Way

Binoculars can introduce you to many members of our home galaxy. Start with star clusters close to Earth. They cover a larger area of the sky than other, more distant clusters that require a telescope.

Beginning each autumn and into the spring, look for a tiny dipper-like cluster of stars named the Pleiades or Seven Sisters. Or look for them in the morning sky starting in July. The cluster is small yet distinctively dipper-like. While most people can only see six stars here with the unaided eye, binoculars reveal many more, plus a dainty chain of stars extending off to one side. The Pleiades star cluster looks big and distinctive because it’s relatively close, about 400 light-years from Earth. These stars were born around the same time and are still bound by gravity. They’re very young, around 20 million years old, compared to our sun’s roughly five billion years.

Stars in a cluster all formed from the same gas cloud. You can see what the Pleiades might have looked like in a primordial state by shifting your gaze to the prominent constellation Orion the Hunter. Look for Orion’s sword stars, just below his prominent belt stars. If the night is crisp and clear, and you’re away from urban streetlight glare, unaided eyes will show that the sword isn’t entirely composed of stars. Binoculars show a steady patch of glowing gas where, right at this moment, a star cluster is being born. This is the Orion Nebula. A summertime counterpart is the Lagoon Nebula, in Sagittarius the Archer.

With star factories like the Orion Nebula, we aren’t really seeing the young stars themselves. They’re buried deep within the nebula, bathing the gas cloud with ultraviolet radiation and making it glow. In a few tens of thousands of years, stellar winds from these young, energetic stars will blow away their gaseous cocoons to reveal a newly minted star cluster.

Scan along the Milky Way to see still more sights that hint at our home galaxy’s complexity. First, there’s the Milky Way glow itself; just a casual glance through binoculars will reveal that it is still more stars we can’t resolve with our eyes … hundreds of thousands of them. Periodically, while scanning, you might sweep past what appears to be blob-like, black voids in the stellar sheen. These are dark, non-glowing pockets of gas and dust that we see silhouetted against the stellar backdrop. This is the stuff of future star and solar systems, just waiting around to coalesce into new suns.

6. View beyond the Milky Way

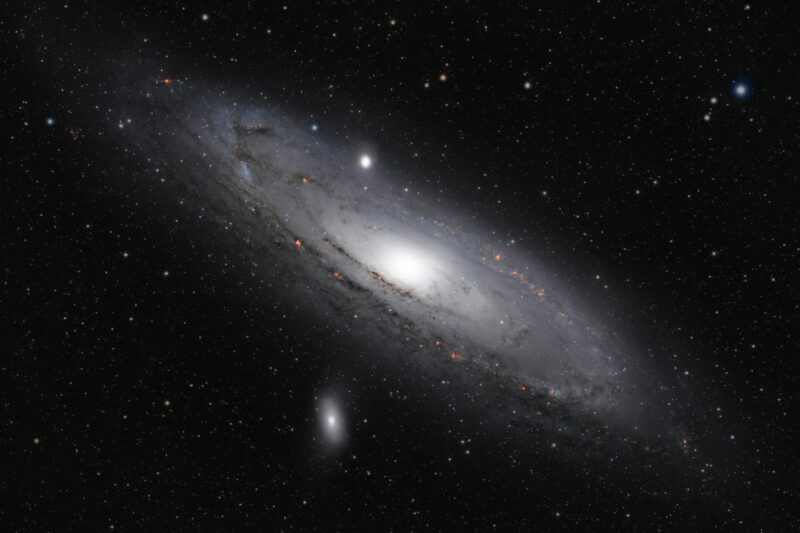

Let’s leap out of our galaxy for the final stop in our binocular tour. Throughout fall and winter, Andromeda the Chained Lady reigns high in the sky during Northern Hemisphere autumns and winters. Centered in the star pattern is an oval patch of light, readily visible to the unaided eye away from urban lights. Binoculars will show it even better.

It’s a whole other galaxy like our own, shining across the vastness of intergalactic space. Light from the Andromeda galaxy has traveled so far that it’s taken more than two million years to reach us. Two smaller companions visible through binoculars on a dark, transparent night are the Andromeda galaxy’s version of our Milky Way’s Magellanic Clouds. These small, orbiting, irregularly shaped galaxies will eventually be torn apart by their parent galaxy’s gravity.

Such sights, from lunar wastelands to the glow of a nearby island universe, are all within reach of a pair of handheld optics, really small telescopes in their own right: your binoculars.

John Shibley wrote the original draft of this article, years ago, and we’ve been expanding it and updating it ever since. Thanks, John!

Bottom line: Want to know how to use binoculars for stargazing? Follow our top six tips to get the most out of viewing the night sky with a little optical aid.