Do you think of the Milky Way as a starry band across a dark night sky? Or do you think of it as a great spiral galaxy in space? Both are correct. Both refer to our home galaxy, our local island in the vast ocean of the universe, composed of hundreds of billions of stars, one of which is our sun.

Long ago, it was possible for everybody in the world to see a dark, star-strewn sky when they looked heavenward at night. In those ancient times, humans looked to the starry sky and saw a ghostly band of light arcing from horizon to horizon. This graceful arc of light moved across the sky with the seasons. The most casual sky-watchers could notice that darkness obscured parts of the band, which we now know to be vast clouds of dust.

Myths of the Milky Way

Myths and legends grew up in different cultures around this mysterious apparition in the heavens. Each culture explained this band of light in the sky according to its own beliefs. To the ancient Armenians, it was straw strewn across the sky by the god Vahagn. In eastern Asia, it was the Silvery River of Heaven. The Finns and Estonians saw it as the Pathway of the Birds.

Meanwhile, because ancient Greek and Roman legends and myths came to dominate western culture, it was their interpretations that were passed down to a majority of languages. Both the Greeks and the Romans saw the starry band as a river of milk. The Greek myth said it was milk from the breast of the goddess Hera, divine wife of Zeus. The Romans saw the river of light as milk from their goddess Ops.

Thus it was bequeathed the name by which, today, we know that ghostly arc stretching across the sky: the Milky Way.

Observing the river of stars

When you are standing under a completely dark, starry sky, away from light pollution, the Milky Way appears like a cloud across the cosmos. But that cloud betrays no clue as to what it actually is. Until the invention of the telescope, no human could have known the nature of the Milky Way.

Just point even a small telescope anywhere along its length and you will be rewarded with a beautiful sight. What appears as a cloud to the unaided eye resolves into countless stars. Their distance and close relative proximity to each other do not permit us to pick them out individually with just our eyes.

It’s the same way a raincloud looks solid in the sky but actually consists of countless water droplets. The stars of the Milky Way merge together into a single band of light. But through a telescope, we see the Milky Way for what it truly is: a spiral arm of our galaxy.

What is the Milky Way?

Thus we arrive at the second answer to the question of what the Milky Way is. To astronomers, it is the name given to the entire galaxy we live in, not just the part of it we see in the sky. If this seems confusing, we must acknowledge the need for our galaxy to have a name.

Many other galaxies are designated by catalog numbers rather than names, for example the New General Catalogue. First published in 1888, it merely assigns a sequential number to each. More recent catalog numbers contain information of far more use to astronomers, for example, the galaxy’s location on the sky and during which survey it was discovered. Moreover, a galaxy may appear in more than one catalog and thus possess more than one designation. For example, the galaxy NGC 2470 is also known as 2MFGC 6271.

Other galaxies, particularly those brighter and closer, received names from astronomers of the 17th and 18th centuries. The names reflected their appearance: the Pinwheel, the Sombrero, the Sunflower, the Cartwheel, the cigar and so forth. These names came long before any systematic sky surveys with numerical labeling systems.

In time, the galaxies with descriptive labels received catalog numbers as well. Yet, our own galaxy does not appear in any index of galaxies. So, it needed a name for astronomers to refer to it by. Thus we call it the Milky Way instead of the galaxy or our galaxy. That name refers to both that river of light across the sky, which is part of our galaxy, and the galaxy as a whole. When not using the name, astronomers refer to it with a capital G (the Galaxy), and all other galaxies with a lowercase g.

Where is the sun in our galaxy?

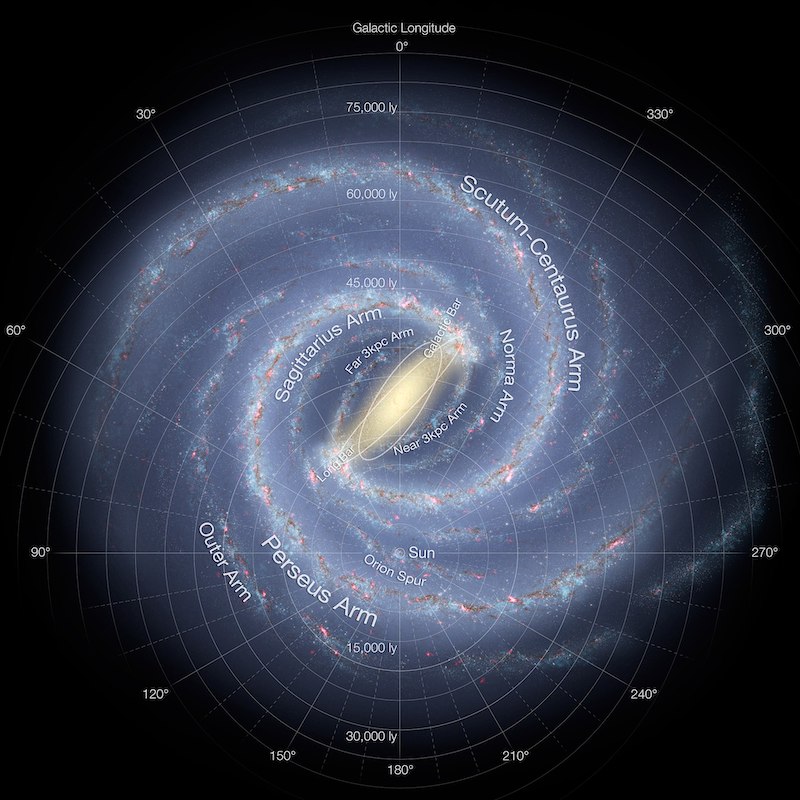

Our solar system lies about 2/3 of the way out from the galactic center. We’re 26,000 light-years from the center, or 153,000 trillion miles (246,000 trillion km).

When we look toward the edge of the galaxy, we see the Orion-Cygnus Arm (or the Orion spur). The solar system is just on the inner edge of this spiral arm.

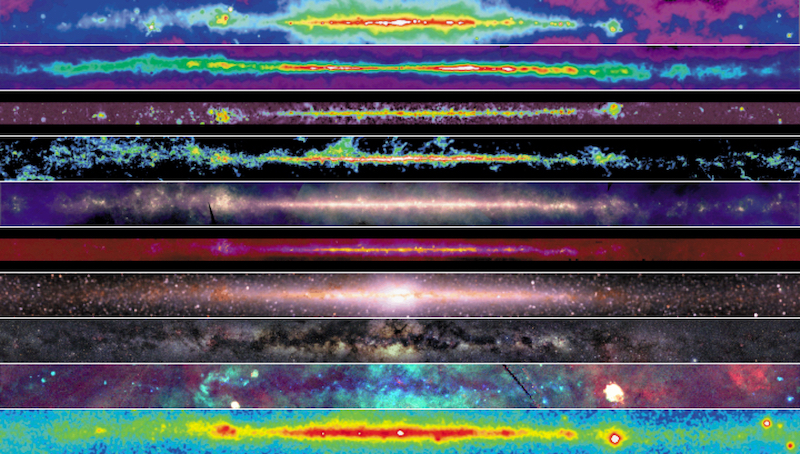

Or we can look toward the center of the galaxy, in the direction of Sagittarius. Vast clouds of dark gas hide the galactic center from us. Only in recent decades have astronomers pierced that dusty fog with infrared telescopes. A study of around 100 stars at the galactic center revealed that those giant clouds of dark dust were hiding a monster: a black hole. This black hole – known as Sagittarius A* – has a mass four million times that of our sun.

The stats on our galaxy

Our Milky Way galaxy is one of billions in the universe. We do not know exactly how many galaxies exist: a modern estimate vastly increases previous counts to as many as 2 trillion.

The Milky Way is approximately 100,000 light-years across, or 600,000 trillion miles (950,000 trillion km). We do not know its exact age, but we assume it came into being in the very early universe along with most other galaxies: within perhaps a billion years after the Big Bang. Estimates of how many stars live within the Milky Way vary quite considerably, but it seems to be somewhere between 100 billion and double that figure.

Why is there so much variance? Simply because it is so difficult to count the number of stars in the galaxy from our vantage point here on Earth. Imagine being in a banquet room full of people and trying to count everyone without being able to move around the room. From where you are standing, all you can do is make an estimate because people close to you block the view of those farther away. Neither can you see what size and shape the room is. The mass of people hides the edges of the room. It’s exactly the same from our position in the galaxy.

Seeing the city of stars

It is this inability to see the structure of the Milky Way from our location inside it that meant for most of human history we did not even recognize that we live inside a galaxy in the first place. Indeed, we did not even realize what a galaxy is: a vast city of stars, separated from others by even vaster distances.

Without telescopes, we couldn’t see most of the other galaxies in the sky. The unaided eye can only see three of them: from the Northern Hemisphere we can see the Andromeda galaxy. Also known as M31, the Andromeda galaxy lies some two million light-years from us. In fact, it’s the farthest object we can see with our eyes alone, under dark skies. The skies in the Southern Hemisphere also have the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds, two amorphous dwarf galaxies orbiting our own. They are far larger and brighter in the sky than M31 simply because they are much closer to us.

Other galaxies in the universe

Until the 1910s, astronomers had not observationally confirmed the existence of other galaxies. Astronomers long believed that those fuzzy patches of light they saw through their telescopes were nebulae, vast clouds of gas and dust in our own galaxy.

But the concept of other galaxies was born earlier, in the early and mid-18th century. Swedish philosopher and scientist Emanuel Swedenborg and English astronomer Thomas Wright apparently conceived the idea independently of each other. Building upon the work of Wright, German philosopher Immanuel Kant referred to galaxies as island universes. The first observational evidence came in 1912 by American astronomer Vesto Slipher, who found that the spectra of the “nebulae” he measured were redshifted and thus much further away than astronomers previously thought.

Edwin Hubble and distant galaxies

And then came Edwin Hubble. Through years of painstaking work at the Mount Wilson Observatory in California, he confirmed in the 1920s that we do not live in a unique location. Our galaxy is just one of perhaps trillions.

Hubble came to this realization by studying a type of star known as a Cepheid variable, which pulsates with a regular periodicity. The intrinsic brightness of a Cepheid variable is directly related to its pulsation period: by measuring how long it takes for the star to brighten, fade and brighten again you can calculate how bright it is, that is to say, how much light it emits. Consequently, by observing how bright it appears from the Earth, you can calculate its distance.

It’s like seeing distant car headlights at night and estimating how far away the car is from how bright its lights appear. You can judge the distance of the car because you know all car headlights have about the same brightness.

Cepheid variables in Andromeda

One of Edwin Hubble’s great achievements was the discovery of Cepheid variables in M31, the Andromeda galaxy. Hubble repeatedly photographed Andromeda with the Hooker Telescope. Eventually, he found stars that changed in brightness over a regular period. Performing the calculations, Hubble realized that M31 is not astronomically close to us at all. It’s 2 million light-years away, and it’s a galaxy like our own.

Hubble, for whom this discovery must have been a monumental shock, surmised that our galaxy was no different from M31 and the others he observed. Thus, he relegated us to a position of lesser importance in the universe. This was as big a revelation and diminution of our position in the universe. It was like when we learned that Earth is not the center of the universe.

We do not live in a special or privileged location. The universe does not have any vantage points which are superior to others. Wherever you are in the universe and you look up at the stars, you will see the same thing. Your constellations may be different, but no matter in which direction you look, you see galaxies rushing away from you in all directions as the universe expands, carrying the galaxies along with it.

Until the work by Slipher and Hubble (and others), we did not know the universe was expanding. It took a surprisingly long time for the astronomical community to accept this fact. Even Albert Einstein did not believe it, introducing an arbitrary correction into his calculations on relativity to achieve a static, non-expanding universe. However, Einstein later called this correction his greatest error.

The Milky Way from a distance

So, what does the Milky Way would look like from the outside? How many spiral arms there are? How big is the galaxy and how many stars does it hold? These were questions still unanswered in the 1920s. It took most of the 20th century after Hubble’s discoveries to piece together those answers through a combination of painstaking work with both Earth- and space-based telescopes.

So, if you could travel outside our galaxy, what would it look like? A standard analogy compares it to two fried eggs stuck together back-to-back. The yolk of the egg is known as the Galactic Bulge, a huge globe of stars at the center extending above and below the plane of the galaxy.

Astronomers now think the Milky Way has four spiral arms winding out from its center like the arms of a Catherine wheel. But these arms do not actually meet at the center. A few years ago astronomers discovered that the Milky Way is a barred spiral galaxy. This means a “bar” of stars runs across its center, and the spiral arms extend from either end. Barred spiral galaxies are not uncommon in the universe. But we do not yet understand how that central bar forms.

New discoveries in the Milky Way

Only a few years ago, astronomers made another major discovery. The Milky Way is not a flat disk of stars but has a kink running across it like an extended S. Something has warped the disk. At the moment, the finger points at the gravitational influence of the astronomically close Sagittarius dwarf galaxy. It’s one of perhaps twenty small galaxies that orbit the Milky Way, like moths around a flame. As the Sagittarius galaxy slowly orbits around us, its gravity has pulled on our galaxy’s stars, eventually creating the warp.

Other objects are also bound to the Milky Way. A halo of globular clusters surrounds our galaxy. Globular clusters are concentrations of stars that look like fuzzy golf balls. They contain perhaps a million or so extremely ancient stars.

Discoveries about the Milky Way continue. The study of its nature and origin is accelerating as new astronomical tools become available, such as the European Space Agency’s orbiting Gaia telescope. Gaia is making a three-dimensional map of our galaxy’s stars with exquisite and quite unprecedented accuracy. Read more about Gaia’s 3rd data release.

It’s an extremely exciting time for the study of our galaxy. It is all a far cry from when, thousands of years ago, our ancestors ascribed fantastic beasts and gods to that mysterious band of light they saw as they stood in awe under the starry sky.

Bottom line: Learn about our galaxy, the Milky Way. We discuss the origin of the name, its structure, and the history of how our knowledge has developed over the centuries and continues to develop today.