On November 14, 2016, the moon will be closer to Earth than it’s been since January 26, 1948. It’ll be a full moon and a supermoon. The moon won’t come this close again until November 25, 2034. That makes upcoming full moon the closest and largest supermoon in a period of 86 years! Here are five things you need to know.

Moon equally awesome on November 13 and 14. Here’s the first and most important thing you need to know. Many articles we’ve seen about the coming supermoon say to look for it on November 14. But – for many of us, especially those of us in the Americas – the moon will be just as big and bright (if not bigger and brighter) on November 13.

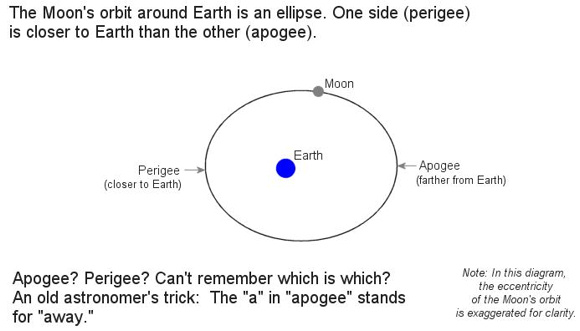

That’s because the moon will reach both the crest of its full phase – and its closest point for the month (perigee) – very early in the day on November 14 according to clocks in the Americas.

Perigee comes at 11:23 UTC (6:23 a.m. ET) on November 14.

Full moon crests two-and-a-half hours later at 13:52 UTC (8:52 a.m. ET) on November 14.

So – for all of us in the Americas – the moon is closest to being full and closest to Earth on the morning of November 14, not the evening. That means that – for all U.S. time zones, including Alaska and Hawaii – the supermoon falls closer to the night of November 13 than November 14. That’s especially true if you are a morning person and plan to observe the supermoon before dawn.

Don’t stress too much about this. The moon will be big and bright both nights! And both nights will be an awesome time to moon-gaze or take photographs.

Are supermoons hype? No. Here’s what to look for The term supermoon is relatively new (read their history here). Before we called them supermoons, we in astronomy called them perigean full moons. Catchy, eh? Well … not so much. Most people ignored these moons until the term supermoon came along.

What’s special about a supermoon? Finely tuned instruments – or composite images – show that a supermoon is indeed closer to Earth and thus bigger than an ordinary full moon.

But most of us can’t detect that difference, using just our eyes. Experienced observers, meanwhile, do sometimes say they can detect a size difference between ordinary full moons and a supermoon.

So, if the rest of us can’t see that a supermoon actually appears larger in our sky, why do we get so excited about supermoons? Here are two things to notice about the November 13-14 supermoon.

First, for all of us, the brightness of the moon will increase noticeably around supermoon-time. All full moons are bright, but supermoons are substantially and noticeably brighter than ordinary full moons. So … notice the brightness, not the bigness, of the moon on November 13 and 14!

Second, the moon’s gravity affects earthly tides, and a supermoon – full moon closest to Earth – pulls harder on Earth’s oceans than an ordinary full moon. That’s why supermoons create higher-than usual tides. Read on …

Supermoons can create super tides. Are supermoons hype? Just ask the oceans! All full moons bring larger-than-usual tides, called spring tides or, in some places, king tides.

Supermoons bring the highest, and lowest, tides of all.

If you live along a coastline, watch for high tides caused by the November 14 supermoon for a period of several days after November 14. These tides tend to follow the date of full moon by a day or two.

Will the high tides cause flooding? Probably not, unless a strong weather system moves into the coastline where you are. That was the case with the high supermoon tides of September, 2015. That supermoon – combined with an 18.6-year lunar cycle, and a tropical storm – caused high tides and some flooding on both sides of the Atlantic.

So keep an eye on the weather around November 14, if you live along the coast. Storms do have a large potential to accentuate high spring tides, especially those caused by supermoons.

Closest moon nearly always a full moon. We wondered … is it the closest moon (in general) since 1948, or the closest full moon? Turns out those two tend to be one and the same.

Because of gravity, and the intriguing interplay of the sun, Earth and moon (and, to a lesser extent, the planets), the closest perigee of any given year is often the one that aligns most closely with full moon.

For the moon to appear full, the sun, Earth and moon need to be aligned, with Earth in the middle. During that particular alignment, the tidal pull of the sun and moon combine to create wide-ranging spring tides. And full moons at perigee create even wider-ranging perigean spring tides.

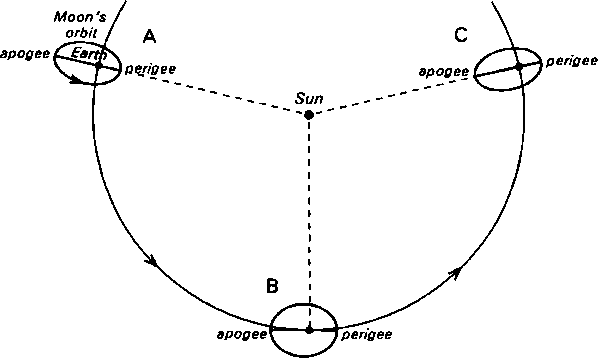

The diagram below helps to explain why the perigee full moon comes especially close to Earth. Take a careful look. Explanation below.

Ready to get technical? Read on!

On the diagram above, the line connecting lunar perigee with lunar apogee defines the moon’s major axis (the longest axis of an ellipse).

When the moon’s major axis (apogee-perigee line) points sunward (A & C on the diagram), the eccentricity (flatness) of the moon’s orbit is increased to a maximum. A greater eccentricity lessens the perigee distance, while increasing the apogee distance.

At A in the diagram, it’s a perigee new moon (supermoon) and an apogee full moon (micro-moon).

Then 3.5 lunar months (some 103 days) later, at B in the diagram, the major axis is at a right angle to the sun-Earth line, so the eccentricity is minimal. At such times, the moon’s orbit is closest to circular. It’s a more distant perigee and closer apogee, with the first quarter and last quarter moons more or less aligning with apogee and perigee.

Then 7 lunar months (206 days) later, the major axis again points sunward. Once again, the eccentricity of the moon’s orbit is increased to a maximum, lessening the perigee distance yet increasing the apogee distance. This time around, it’s a full moon perigee and new moon apogee. See C in the diagram.

Dates for closest/farthest new/full moons in 2016:

April 7: closest new moon

April 22: farthest full moonSeven lunar months later:

October 30: farthest new moon

November 14: closest full moon

Supermoons happen in cycles. Okay, so by now – if you’re a regular EarthSky reader – you’ve figured out that everything in the sky happens in cycles. The supermoon is no exception.

Closest full moons tend to recur in cycles of 14 lunar (synodic) months, because 14 lunar months almost exactly equal 15 returns to perigee (moon’s closest point to Earth).

A lunar month refers to the time period between successive full moons, a mean period of 29.53059 days. An anomalistic month refers to successive returns to perigee, a period of 27.55455 days. Hence:

14 lunar months x 29.53059 days = 413.428 days

15 anomalistic months x 27.55455 days = 413.318 days

This 413-day time period is equal to about 1 year, 1 month, and 18 days.

The full moon and perigee will realign again on January 2, 2018, because the 14th full moon after the November 14, 2016 full moon will fall on that date.

Moon closest to Earth

| Year | Date | Distance | 2011 | March 19 | 356,575 km | 2012 | May 6 | 356,955 km | 2013 | June 23 | 356,991 km | 2014 | August 10 | 356,896 km | 2015 | September 28 | 356,877 km | 2016 | November 14 | 356,509 km | 2018 | January 2 | 356,565 km |

Looking further into the future, the perigee full moon will come closer than 356,500 kilometers for the first time in the 21st century (2001-2100) on November 25, 2034 (356,446 km). The closest full moon of the 21st century will fall on December 6, 2052 (356,425 km).

For the moon to come closer than 356,400 kilometers (221,457 miles) is quite a feat. In fact, this won’t happen at all in the 21st century (2001-2100) or the 22nd century (2101-2200). The last time the full moon perigee swung this close to Earth was on January 14, 1930 (356,397 km), and the next time won’t be till January 1, 2257 (356,371 km).

Bottom line: Enjoy the November 14, 2016 supermoon. Don’t forget to watch for it on November 13 as well, especially if you live in the Americas. Two things to watch for: the moon’s brightness, and especially high tides in the days following the full moon.