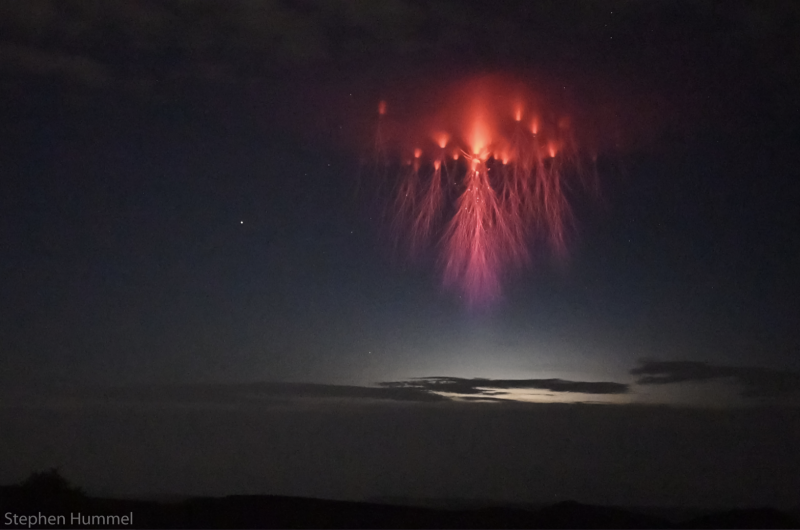

What are lightning sprites?

Did you know that lightning sprites exist above some thunderstorms? Sprites aren’t terribly well known, except to meteorologists, nature photographers and others who study the skies. They aren’t especially rare, but they’re fleeting and hard to capture with a camera. Lightning sprites are electrical discharges high in Earth’s atmosphere. They’re associated with thunderstorms, but they’re not born in the same clouds that send us rain. Thunderstorms – in fact all earthly weather – happen in the layer of Earth’s atmosphere called the troposphere, which extends from Earth’s surface to about 4 to 12 miles (about 6 to 19 km) up. Lightning sprites – also known as red sprites – happen in Earth’s mesosphere, up to 50 miles (80 km) high in the sky.

From a distance they look small, but they’re not

So when you’re standing on Earth’s surface and you spot one, it appears relatively small, even though, in fact, sprites can be some 30 miles (50 km) across. As Matthew Cappucci of the Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang said in an article about lightning sprites a few years ago:

Imagine one electrical discharge spanning the distance from Baltimore to Washington, D.C.

Cappucci also commented:

Although sprites are poorly understood, atmospheric electrodynamicists have figured out the basics behind their formation. Sprites are often triggered by a strong, positive bolt of ordinary lightning near the ground. They’re thought to be a balancing mechanism that the atmosphere uses to dispense charges vertically. It’s a quick process that takes less than a tenth of a second.

That’s what makes hunting for sprites so tough. Blink and you’ll miss them.

A fleeting phenomenon

The fleeting aspect of lightning sprites probably explains why – when people first see photos of them – they’re surprised that such a strange-looking weather phenomenon even exists.

Also, it hasn’t been that many years since lightning sprites were confirmed. In the 20th century, pilots spoke of “flashes above thunderstorms.” It wasn’t until 1989 that someone captured lightning sprites as we know them today on film. Experimental physicist John R. Winckler (1916-2001) happened to capture one while testing a low-light television camera.

Today, people around the world routinely capture photos of lightning sprites. You’ll find many photos of them in this gallery from SpaceWeather.com.

How to photograph lightning sprites

To photograph a sprite, you need a dark sky and a clear view toward a distant thunderstorm. The sky needs to be dark, because you’ll be taking long exposures; too much stray light in your sky will wash out your photo and make capturing sprites impossible. One of the most successful sprite photographers in the U.S., and likely in the world, is Paul M. Smith. He captured the sprite below in June 2020.

Paul spoke to EarthSky about his top tips for photographing lightning sprites. He recommends that you be under dark skies, let your eyes adjust to the darkness, and be persistent! Paul hosts workshops multiple times a year for those who want to learn how to photograph lightning sprites. He said the same tips apply to those who just want to see one with their eyes alone as for those who want to photograph them. He also said:

Some storms may produce one sprite all night, whereas others may have a sprite a minute, so activity obviously plays a big role.

You can follow Paul on Twitter: @PaulMSmithPhoto. Or find him on YouTube.

Massive Jellyfish sprite up close from Kansas storms last night . 06/21/20 0415UTC. Every year for last 3 years I have managed good sprites on Fathers day. Good tradition :) #okwx #kswx @stormhour @ASIM_Payload @NASA pic.twitter.com/4xFaqsaHld

— Paul M Smith (@PaulMSmithPhoto) June 21, 2020

More lightning sprite photos

Want more photos of lightning sprites? Try these:

Lightning sprites over the Andes in early 2020, from Yuri Beletsky

Lightning sprites over Oklahoma in 2018, from Paul Smith

Captures of elusive red sprites from the International Space Station

Bottom line: Lightning sprites, or red sprites, often occurring in tandem with lightning, are short-lived electrical discharges that flash high above thunderstorms in the mesosphere layer of the atmosphere.