Water worlds? Or thick atmospheres?

Water is common in our solar system. We find it in both liquid and ice form, on Earth and other planets. And water is key to life as we know it. How about in distant solar systems? How many exoplanets – worlds orbiting distant stars – have water? Is water on exoplanets common … or rare? We don’t know yet, in part because it’s been hard to tell the difference between an ocean planet and one with a thick hydrogen atmosphere. Now, in a study being called a potential breakthrough, a team of researchers has figured out a way to test for water on sub-Neptune exoplanets, including some of the larger super-Earths.

The study has been accepted for publication in the peer-reviewed Astrophysical Journal Letters. It can currently be read in preprint form on arXiv. The new research comes from Caltech, MIT, and other institutions. Planetary scientist Renyu Hu at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory is the lead author. Hu told EarthSky in an email:

[Our] paper mostly addresses planets in the 1.7-3.5 Earth-radii range. From the exoplanet survey of Kepler and many follow-up observations, we now know that the 1.7-3.5 Earth radii planets constitute a different planet population from the <1.7-Earth-radii planets.

The news about Hu and team’s new computer model – designed to reveal water worlds on sub-Neptune exoplanets – was also featured in an article in Inverse on September 1, 2021.

The terminology can get confusing here. There’s overlap between the terms super-Earth, sub-Neptune and mini-Neptune. Super-Earths have a lower upper size limit than mini-Neptunes, but they’re still between Earth and Neptune in size and mass. When you hear super-Earth, think big, rocky world. Kind of like Earth on steroids. A big rocky super-Earth could have oceans on its surface.

When you hear sub-Neptune or mini-Neptune, think more about planets with thick or thin gaseous atmospheres, made mostly of hydrogen. And think of possible oceans, even global oceans.

Oceans on sub-Neptunes

Sub-Neptunes are much larger and more massive than Earth. A sub-Neptune might have a smaller radius than Neptune, but a larger mass. Or it might have a smaller mass than Neptune, but a larger radius … in which case it might be called a super-puff. You can see that nature hasn’t made exoplanet classification easy for us. In any case, we don’t have any sub-Neptunes in our own solar system (unless Planet Nine turns out to be one). But sub-Neptunes and mini-Neptunes are among the most common types of planets that have been found in our galaxy. How can we find out if they have water on their surfaces, even oceans, as opposed to just thick atmospheres? That’s an important question if we want to know whether these worlds – which constitute a large fraction of the known exoplanets – might be habitable.

Using their new computer model, Hu and his team found that about 10% to 20% of sub-Neptunes could have oceans and be potentially habitable. Since there are estimated to be billions of these planets in our galaxy alone, that’s potentially a lot of worlds…

Modeling an ocean world

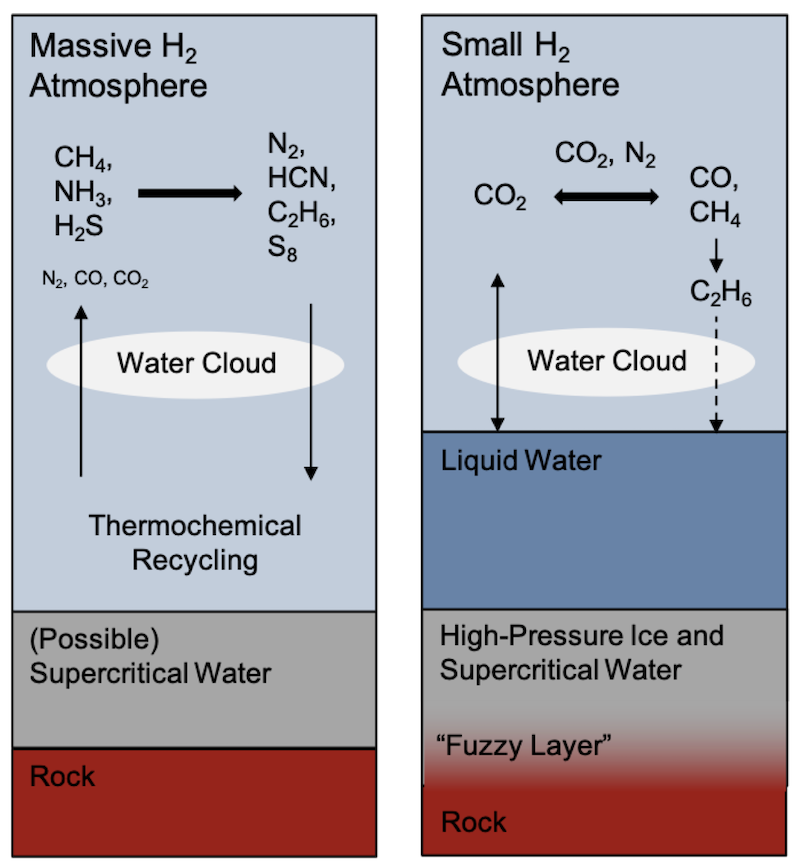

So how did the researchers create a tool for determining which sub-Neptunes might have oceans and even be habitable? They created a computer model of an ocean-covered planet, orbiting a red dwarf star (the most common type of star in our galaxy). They gave it the same amount of radiation from its star that Earth receives from the sun. Then they tweaked the model, giving their world a thick or a thin atmosphere.

The researchers wanted to see details in the atmospheric chemistry between worlds with both thin and thick atmospheres. Thicker, denser atmospheres on such worlds tend to be composed of hydrogen or helium. Thinner atmospheres would likely be made mostly of carbon dioxide or nitrogen.

Atmospheres and oceans are connected

On Earth, our atmosphere and our oceans are linked. Together, they’re responsible for our world’s weather and climate. And, not surprisingly, they’re also linked on sub-Neptune exoplanets. Distant exoplanets – between Earth and Neptune in size and mass, and with thinner carbon dioxide or nitrogen atmospheres – would be the most likely to have oceans, according to Hu and his team. Distant exoplanets with a thicker hydrogen or helium atmosphere would be less likely, as the temperatures would be too hot at the bottom of their atmospheres for oceans to exist. Consider Neptune in our solar system, with its thick atmosphere; no ocean resides beneath Neptune’s clouds. Hu and his team hope that other scientists will use their work as a jumping off point. As outlined in the paper:

The recent discovery and initial characterization of sub-Neptune-sized exoplanets that receive stellar irradiance of approximately Earth’s raised the prospect of finding habitable planets in the coming decade, because some of these temperate planets may support liquid water oceans if they do not have massive [hydrogen/helium] envelopes and are thus not too hot at the bottom of the envelopes.

Hycean water worlds?

By the way, another recent study found that there may be a class of exoplanets of interest to this discussion, now being called Hycean planets. These are mini-Neptunes or super-Earths up to 2.6 times the diameter of Earth, with temperatures up to 200 degrees C (about 400 degrees F) and thick hydrogen atmospheres. In some cases, according to the study, these planets could also host global oceans.

That might sound contrary to this new study. We just said that worlds with thick atmospheres (like Neptune) probably don’t have oceans under their thick blankets of clouds. But it shows nature’s subtlety. Nature is vastly more subtle than any computer model. Good scientists understand that, and know there are uncounted scenarios in which large planets could maintain or not maintain oceans. They know that small changes in mass, temperature and so on can make make differences in how a planet’s ocean-atmosphere system plays out. Plus this is a new field, and so astronomers are still learning and debating some things. All in all, there’s a lot to learn about what these kinds of planets are really like.

There are now 4,000+ known exoplanets. When will we know how many might have oceans? Astronomers are looking to new telescopes, such as Hubble’s successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, currently scheduled for launch on December 18, 2021. They hope the Webb will be able to analyze the atmospheres of some of these distant worlds and determine which ones have atmospheres that could support oceans.

Bottom line: Could there be oceans on sub-Neptunes? A new study from various institutions suggests that up to 20% of these worlds may have liquid water oceans, and could even be potentially habitable.