In recent decades, astronomers have confirmed a few thousand exoplanets, or planets orbiting distant stars. There are thousands more exoplanet candidates. On December 3, 2018, an international team of astronomers announced a plethora of new worlds to add to the list – not just one or two – but 104!

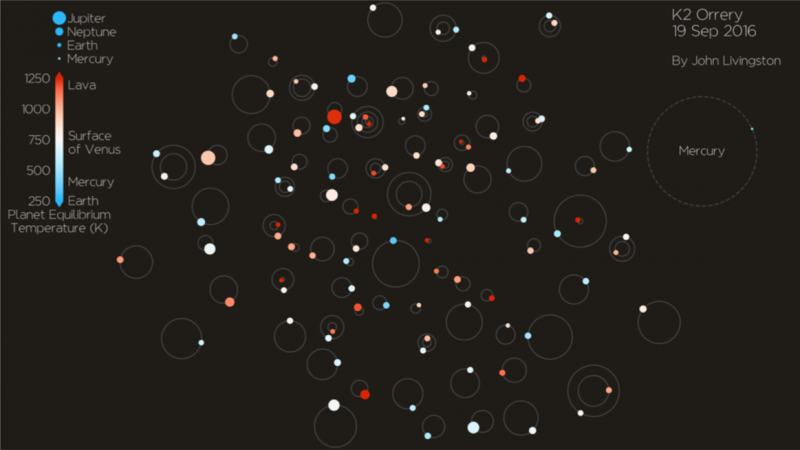

Astronomer John Livingston at the University of Tokyo led the newest of two studies describing the new worlds. He also created the video visualization above, which depicts the newly discovered exoplanet orbits. In the visualization, small exoplanets are Mercury-sized, large ones are Jupiter-sized. The colors indicate those planets’ temperatures; blue indicates roughly Earth’s temperature; white shows temperatures similar to the surface of Venus; and red shows lava-like temperatures. That’s a lot of information, for these distant, newly discovered worlds!

In the meantime, Livingston and colleagues’ results have also been published in a new peer-reviewed paper in Astronomical Journal.

This new planetary haul is particularly exciting when it comes to smaller rocky planets like Earth. As Livingston noted:

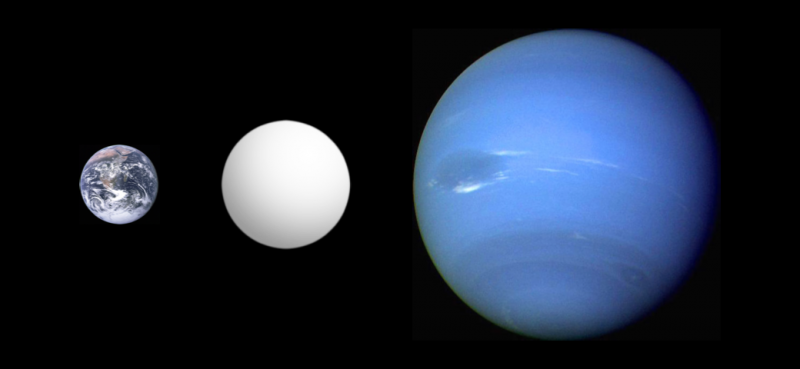

Eighteen of the [newest] 60 planets are less than two times larger than the Earth, and are likely to have rocky compositions with little to no atmosphere.

Little or no atmosphere means those planets don’t have thick, deep atmospheres like the gas or ice giants in our own solar system. Rather, they could be more like Earth and other rocky planets with relatively thinner atmospheres.

Or, in some cases, they might be worlds with little to no atmospheres, like Mercury.

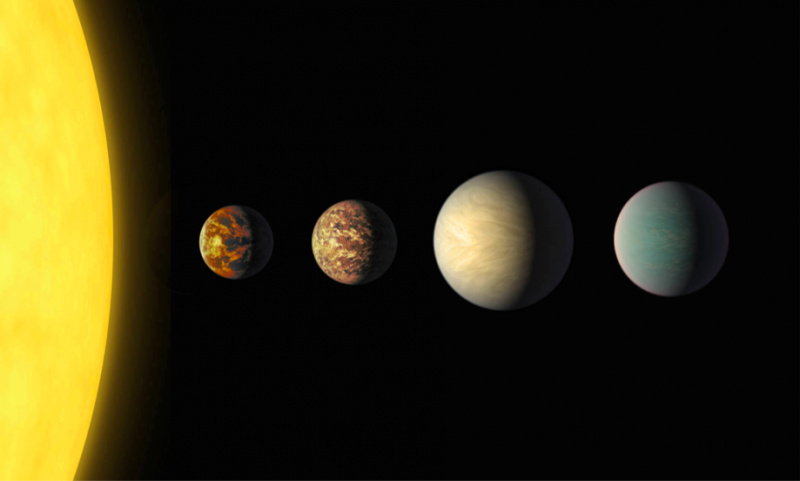

About two dozen of the new planets are in multi-planet systems. Several have orbital periods of less than 24 hours. Astronomers call these worlds ultra-short period (USP) planets. USP planets tend to usually be hot Jupiters, or gas giant planets orbiting very close to their stars.

One of the newly discovered planetary systems, K2-187, has four known planets, including one USP planet. According to Livingston:

This system joins a growing list of USPs in multi-planet systems, which may provide important clues about USP formation pathways.

The announcement of the 104 new exoplanets came in two parts. Researchers from the University of Tokyo and the Astrobiology Center of the National Institutes of Natural Sciences in Japan announced 60 new exoplanets discovered in data from NASA’s Kepler mission and ESA’s Gaia mission.

Those planets are in addition to 44 planets previously found and announced last August.

For Japanese scientists, this is a record number of exoplanets discovered to date, according to John Livingston. He said:

We broke our old record with this new paper, so that makes a total of 104 planets from these two studies.

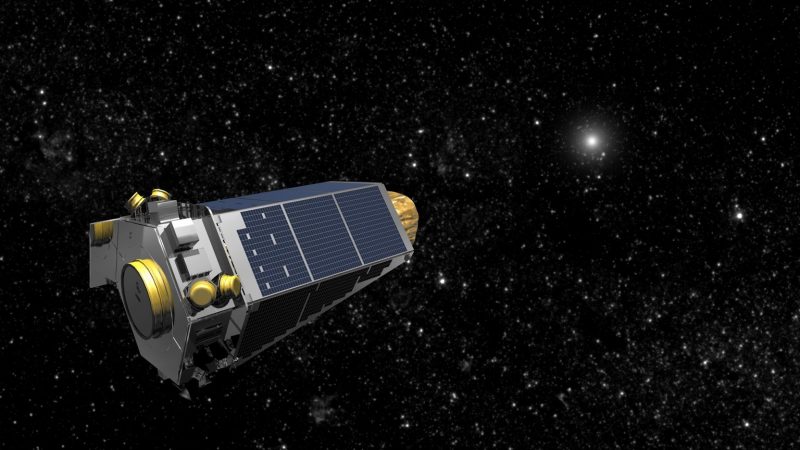

The latest batch of 60 planets is the result of detailed analysis of 155 planet candidates found in data from the second year of K2 mission operations. The precise time series photometry from K2 was combined with precise astrometry from ESA’s Gaia mission, another highly successful mission, whose job is to measure the positions of stars in the sky with unparalleled detail. The astronomers said this work only became possible in 2018, with Gaia’s second data release.

K2 was the modified second phase of the Kepler planet-hunter mission. Kepler’s primary mission ended in 2013, due to a malfunction in one of the telescope’s reaction wheels, which help the telescope remain steady. That was after the spacecraft had already discovered a significant fraction of all known exoplanets. Mission engineers came up with a makeshift remedy for the malfunctioning wheels, but it meant that Kepler’s observing strategy had to change. Even so, during the K2 phase of the mission, Kepler data continued to reveal exoplanets, although at a slower rate than previously.

Now Livingston says he is confident that hundreds more exoplanets from K2 are waiting to be confirmed:

By extrapolating our analysis of these 155 candidates, we estimate that hundreds of planets remain unconfirmed in the K2 data.

The Kepler mission is now over, after the spacecraft finally (as expected) ran out of fuel last month. Now, the torch has been passed to another mission – the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite – aka TESS. Livingston explained:

Although the Kepler Space Telescope has been officially retired by NASA, its successor space telescope, called TESS, has already started collecting data. In just the first month of operations, TESS has already found many new exoplanets, and it will continue to discover many more.

We can look forward to many new exciting discoveries in the coming years.

Bottom line: Several thousand exoplanets – both confirmed and candidates – have been discovered by astronomers so far, and now this new report adds over 100 more to that ever-growing list of strange, new worlds.

Source: Sixty Validated Planets from K2 Campaigns 5–8

Via National Institutes of Natural Sciences of Japan

EarthSky lunar calendars are cool! They make great gifts. Order now. Going fast!