By Vishnu Reddy, University of Arizona

Space debris all the way out to the moon

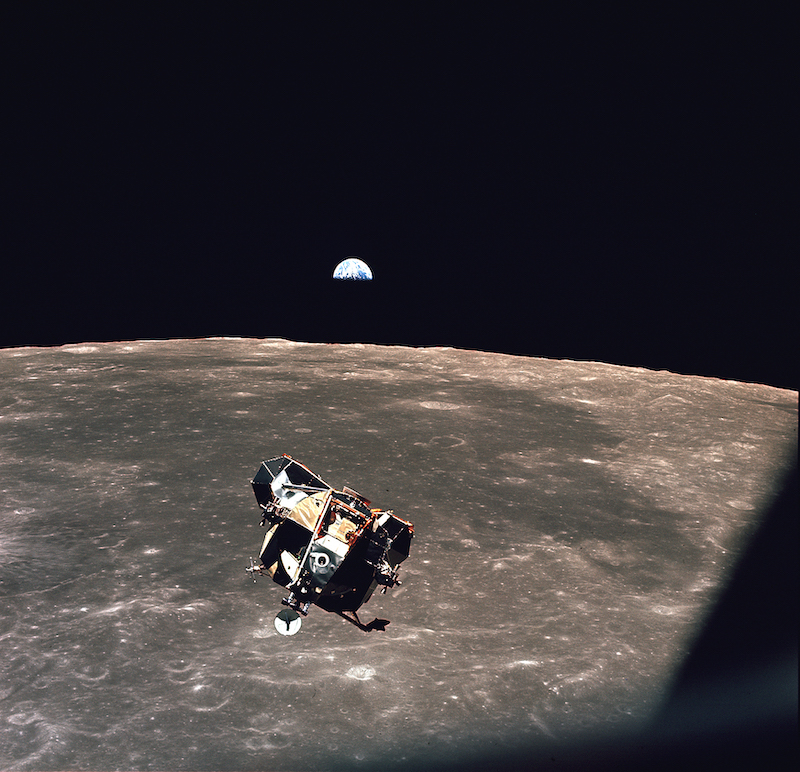

Scientists and government agencies have been worried about the human-made space junk surrounding Earth for decades. But humanity’s starry ambitions are farther reaching than just the space around Earth. Ever since the 1960s, with the launch of the Apollo program and the emergence of the space race between the U.S. and Soviet Union, people have been leaving trash around the moon, too.

Today, experts estimate that there are a few dozen pieces of human-made space junk between Earth and the moon and in the moon’s orbit. These items include rocket bodies, defunct satellites and mission-related debris orbiting in cislunar space. [Cislunar space is the space between the Earth and moon]. This isn’t yet a large amount of junk. But astronomers have very little information about where these pieces of space debris are, let alone what they are and how they got there.

Planning a space junk catalog for the moon

I (Vishnu Reddy) am a planetary scientist. I also run the Space Safety, Security and Sustainability Center (Space4) at The University of Arizona. As the focus of space activities turns to the moon, each future mission will leave more junk in cislunar space. This junk is an emerging problem that could create hazardous conditions for astronauts and spacecraft in the future.

My colleague Roberto Furfaro and I are hoping to help prevent this problem from getting out of hand. Together, we are using telescopes and existing databases on lunar missions to find, describe and track lunar space debris. We will build the world’s first catalog of cislunar space objects.

Abandoned and potentially dangerous

Historically, NASA and the U.S. military have not closely tracked space debris from the many dozens of crewed and robotic missions to the moon. There is no international agency that has monitored lunar objects, either. This lack of oversight is why scientists don’t know the location or orbit of the vast majority of lunar space debris. And these objects won’t simply go away. In the near total vacuum of space, anything left in orbit around the moon or in cislunar space will likely remain there for at least decades.

Risks to lunar missions

This lack of information about human-made objects orbiting the moon poses many risks for lunar missions.

First is the risk of collision. Humanity is at the beginning of a new wave of lunar exploration. Over the next 10 years, six countries and several commercial companies have plans for more than 100 missions. With every mission, the risk of a collision with existing debris increases. So, too, does the total amount of debris as missions leave junk behind.

Crash landings onto the surface of the moon are also a real risk. That’s because the moon does not have a thick atmosphere that can burn up falling space junk. We saw this with the impact of a spent Chinese rocket booster into the far side of the moon in March 2022. My team and I were the ones to finally identify that object as being of Chinese origin. We did that by using telescopes we built to track objects in cislunar space. With both the U.S. and China planning to build lunar bases in the coming years, falling debris could become a real threat to human life and infrastructure on the moon.

Hard to track

If you want to prevent the moon from becoming a cosmic landfill, you need to be able to track cislunar space junk. But doing so is challenging even on a good day for two main reasons: distance and light.

Cislunar space extends about 2.66 million miles (42.8 million km) from Earth. That’s far past the distance within which the U.S. government currently tracks objects in space. But space is not just two-dimensional. The three-dimensional volume of cislunar space is massive. Any objects within it are tiny by comparison.

Light presents another challenge. Just like the moon itself, the brightness of an object in cislunar space depends on how much sunlight the object reflects. During a crescent moon, lunar debris appears dim and low in the evening sky, making it hard to find. During a full moon, the same objects are high in the sky. They are brighter due to more sunlight hitting them, but they blend in with the bright glare that surrounds a full moon. Spotting objects during a full moon is like trying to find a firefly’s faint glow next to a bright search light. Within the lunar glare is the Cone of Shame, named for the difficulty in tracking objects within it.

Curating the space junk catalog

Because of the difficulty and lack of adequate resources to track objects near the moon, there is no group or organization consistently doing so today. So, in 2020, Furfaro and I took on the challenge to discover, track and catalog human-made debris in cislunar space.

First, we linked historical observations from various telescopes and databases to each other to identify and confirm already known cislunar objects. Then, realizing there were no dedicated telescopes scanning the night sky for cislunar objects, my students at The University of Arizona and I built one. In late 2020, we finished building a 24-inch-diameter (0.6-meter-diameter) telescope, which is at the Biosphere 2 Observatory near Tucson.

The first object we tracked was Chang’e 5, China’s first lunar sample return mission. The large rocket launched on November 23, 2020, headed toward the moon. Despite the powerful lunar glare, my students and I were able to track Chang’e 5 to a distance of 12,354 miles (19,881 km) from the moon. That’s deep into the Cone of Shame. With this success, we started tracking newly launched cislunar payloads, adding them to our nascent catalog so we can calculate and predict their orbits to prevent them from getting lost.

To characterize both old and new space debris, once we figure out where an object is, we use optical and near-infrared telescopes on Earth to capture the object’s spectral signature. That’s the specific wavelengths of light that bounce off an object’s surface. By doing this, we can figure out what an object’s made of and identify it. This is how we identified the mystery rocket booster that crashed into the moon in 2022. We can also measure changes in the light bouncing off the object over time to determine how fast that object is spinning. This can also help with identification.

Adding to the cislunar space junk catalog

Over the last two years, we have become better and better at finding and identifying objects in cislunar space. At first we were happy to identify the school bus-sized Chang’e 5 spacecraft. Now, we are able to track CubeSats no bigger than a cereal box, such as NASA’s Lunar Flashlight.

To date, my team has been able to identify a few dozen pieces of debris in cislunar space. And we’re continuing to add to our ever-expanding catalog. The vast majority of the work ahead comprises continued observations and matching objects to known missions to confirm what objects are out there and where they came from.

While there is still a long way to go, these efforts will ultimately form the basis for a catalog that will help lead to safer, more sustainable use of cislunar orbital space as humanity begins its expansion off Earth.![]()

Vishnu Reddy, Professor of Planetary Science, The University of Arizona

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bottom line: With more moon missions in the works, scientists are creating a space junk catalog to track debris between Earth and the moon.