Carbon = life’s building blocks

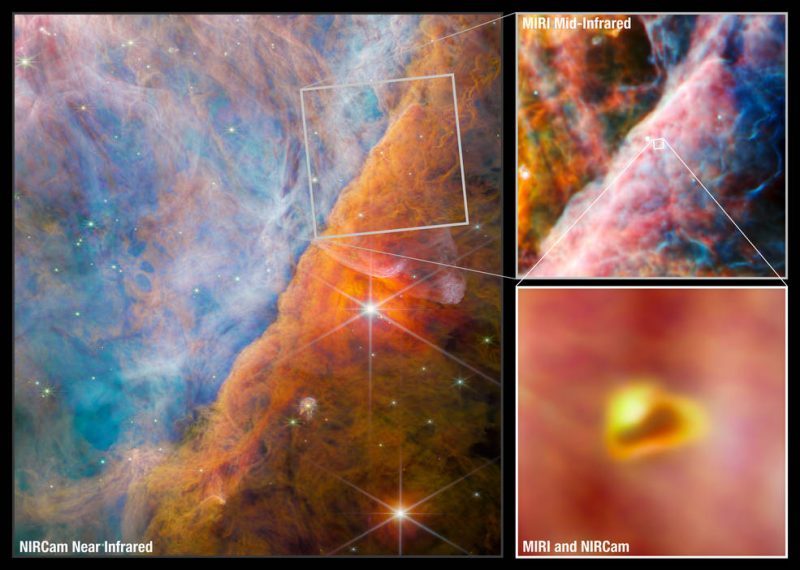

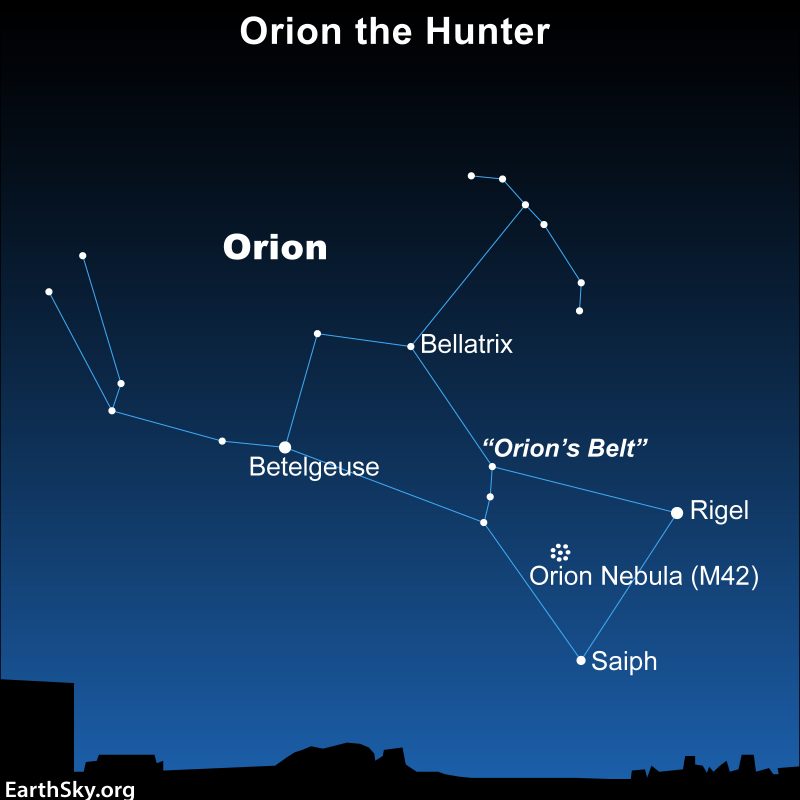

NASA said on June 26, 2023, that scientists have used the Webb space telescope to detect a new carbon compound in space, for the first time. More specifically, they found it in a young star system, called d203-506. It’s located some 1,350 light-years away in the famous Orion Nebula, one of the easiest to spot star-forming regions in the night sky. What’s so great about carbon? Only that, without it, life as we know it couldn’t exist. So consequently, carbon compounds in space are key to the search for life elsewhere.

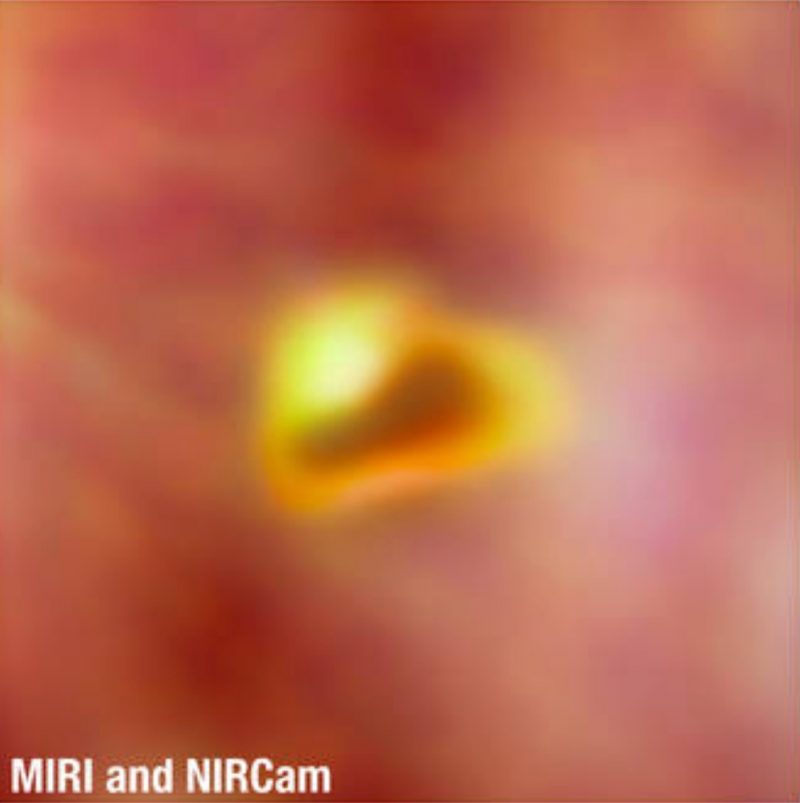

The system d203-506 contains a red dwarf star, a common sort of star. In addition, it also contains one of many planet-forming disks – aka protoplanetary disks – now known to exist in our home galaxy, the Milky Way. At one time, our sun had a disk of gas and dust around it, similar to what we find in this system. And indeed, it was from that sun-centered disk that the planets, including Earth with its wondrous assemblage of life, arose 4 1/2 billion years ago.

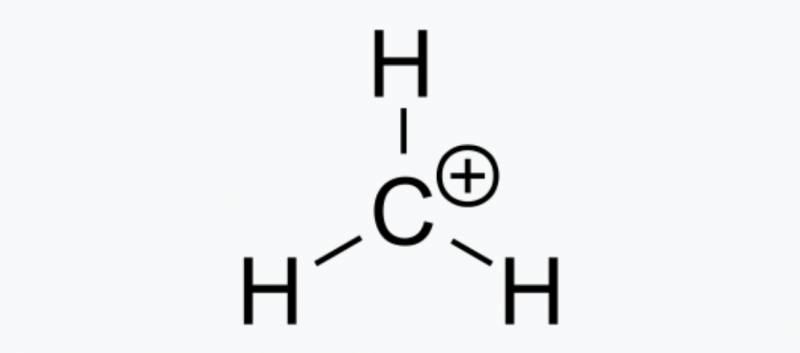

The carbon compound is known as methyl cation (pronounced cat-eye-on) or, to scientists, CH3+. And it’s important, because it aids the formation of more complex carbon-based molecules. They include those that make up our human bodies and the bodies of other living things.

They found the carbon in a young star system

The Orion Nebula has long been known as a stellar nursery. Indeed, it’s a place where new stars are forming. So it’s no surprise that modern astronomical instruments are beginning to find planet-forming disks around some of these stars. Now, probing more deeply, astronomers have now found carbon compounds in one of these disks.

The astronomers’ June 26 statement said they are:

… working to understand both how life developed on Earth, and how it could potentially develop elsewhere in our universe. The study of interstellar organic (carbon-containing) chemistry, which Webb is opening in new ways, is an area of keen fascination to many astronomers.

The unique capabilities of Webb made it an ideal observatory to search for this crucial molecule. Webb’s exquisite spatial and spectral resolution [Ed note: its ability to see clearly], as well as its sensitivity, all contributed to the team’s success.

In particular, Webb’s detection of a series of key emission lines from CH3+ cemented the discovery.

Additionally, a member of the science team, Marie-Aline Martin-Drumel of the University of Paris-Saclay in France, commented:

This detection not only validates the incredible sensitivity of Webb but also confirms the postulated central importance of CH3+ in interstellar chemistry.

UV bombardment of life’s building blocks

Also, it’s worth noting that the star in the d203-506 system and its planet-forming disk are being bombarded by strong ultraviolet (UV) light from nearby hot, young, massive stars.

Moreover, scientists believe that most planet-forming disks go through a period of such intense UV radiation. Generally, this is because stars tend to form in groups that often include massive, UV-producing stars.

Typically, NASA said, UV radiation is expected to destroy complex organic molecules, in which case the discovery of CH3+ might seem to be a surprise.

But, in this case, the team predicts that UV radiation might provide the necessary source of energy for CH3+ to form in the first place.

And, once formed, it then promotes additional chemical reactions to build more complex carbon molecules.

Unique molecules

Additionally, the scientists’ statement also noted that the molecules astronomers see in d203-506 are quite different from those they’ve seen before in planet-forming disk. In particular, they couldn’t detect any signs of water. Olivier Berné of the French National Centre for Scientific Research in Toulouse, lead author of the study, explained:

This clearly shows that ultraviolet radiation can completely change the chemistry of a protoplanetary disk. It might actually play a critical role in the early chemical stages of the origins of life.

Bottom line: Scientists have found carbon compounds – life’s building blocks – in a planet-forming disk, encircling a star in the famous Orion Nebula.

Source: Formation of the Methyl Cation by Photochemistry in a Protoplanetary Disk