Shortly before 4 a.m. (12:00 UTC) last week (January 7, 2021), Congress confirmed Democrat Joe Biden as the United States presidential election winner. Vice President Mike Pence, presiding over the joint session, announced the tally, 306-232. Whatever your political leanings, if you are a space fan, you watched closely during the Donald Trump administration as it supported NASA’s long-term goal of sending astronauts to Mars. And you saw our nation’s course change during Trump’s tenure to a short-term goal of returning the next man and first woman to the moon by 2024, with the Artemis program. Overall – under Donald Trump – America’s gaze shifted more strongly to human missions to the moon and to Mars. Will that focus continue under President Joe Biden? How can NASA expect to fare under Biden?

Here is some context. In 2017, Trump appointed Jim Bridenstine, a Republican congressman from Oklahoma, to run NASA. The Congress – and the science and space communities – were caught off guard because NASA is typically run by a scientist or a former astronaut or other apolitical space expert. Bridenstine was eventually confirmed by the Senate in April 2018, more than seven months after his appointment. Despite his lack of space or science background, in two years as NASA administrator he appeared to gain the respect of many. Immediately after Biden’s election, however, in early November 2020, Bridenstine announced he would resign.

More context. The wonderful missions out into our solar system that we hear so much about – the much-loved Mars fleet, New Horizons’ dramatic sweep past Pluto, Cassini’s 13 years at Saturn and so on – are robotic missions. The workhorse missions to understand our own Earth and sun are robotic missions. There’s been a decades-long attempt to balance the smaller robotic missions like these, which bear so much fruit, with the bigger, flashier, more expensive missions that could carry human beings into the solar system. The decision to launch a Cassini or a New Horizons has to be made decades in advance; indeed, some of the most visible and stirring robotic missions of this century so far were the lifetime work of scientists begun in the last decades of the 20th century. Why can’t we have both kinds of missions? Why indeed? But it does seem that – in terms of the space program since it began in the late 1950s – the focus has shifted between human missions and robotic missions. That’s just something to bear in mind.

How will the U.S. space program change under a President Joe Biden? Biden is a known quantity in many ways, having served for decades in the Senate and eight years as vice president in the Obama administration. But his plans for NASA and America’s space program are less clear.

The Biden campaign made little mention of its space priorities, apart from a few statements made during the Crew Dragon Demo 2 launch on May 30, 2020, the first launch of NASA astronauts from American soil since 2011. Specifically, Biden wrote on his website:

As president, I look forward to leading a bold space program that will continue to send astronaut heroes to expand our exploration and scientific frontiers through investments in research and technology to help millions of people here on Earth.

The Democratic Party platform – a practical list of Democratic Party objectives for the next four years – was proposed to the 2020 Platform Committee at its meeting on July 27, 2020. While thorough in its claims to upholding national health, economic growth, and racial equity, among other things, its only mention of the space program was condensed to a few lines. However brief, it was considered to be promising in the opinion of John Logsdon, the founder of George Washington University’s Space Policy Institute. The Democratic platform not only endorsed NASA’s current plans, but mentioned its priorities ranging from science and technology development to continued operation of the International Space Station and human space exploration:

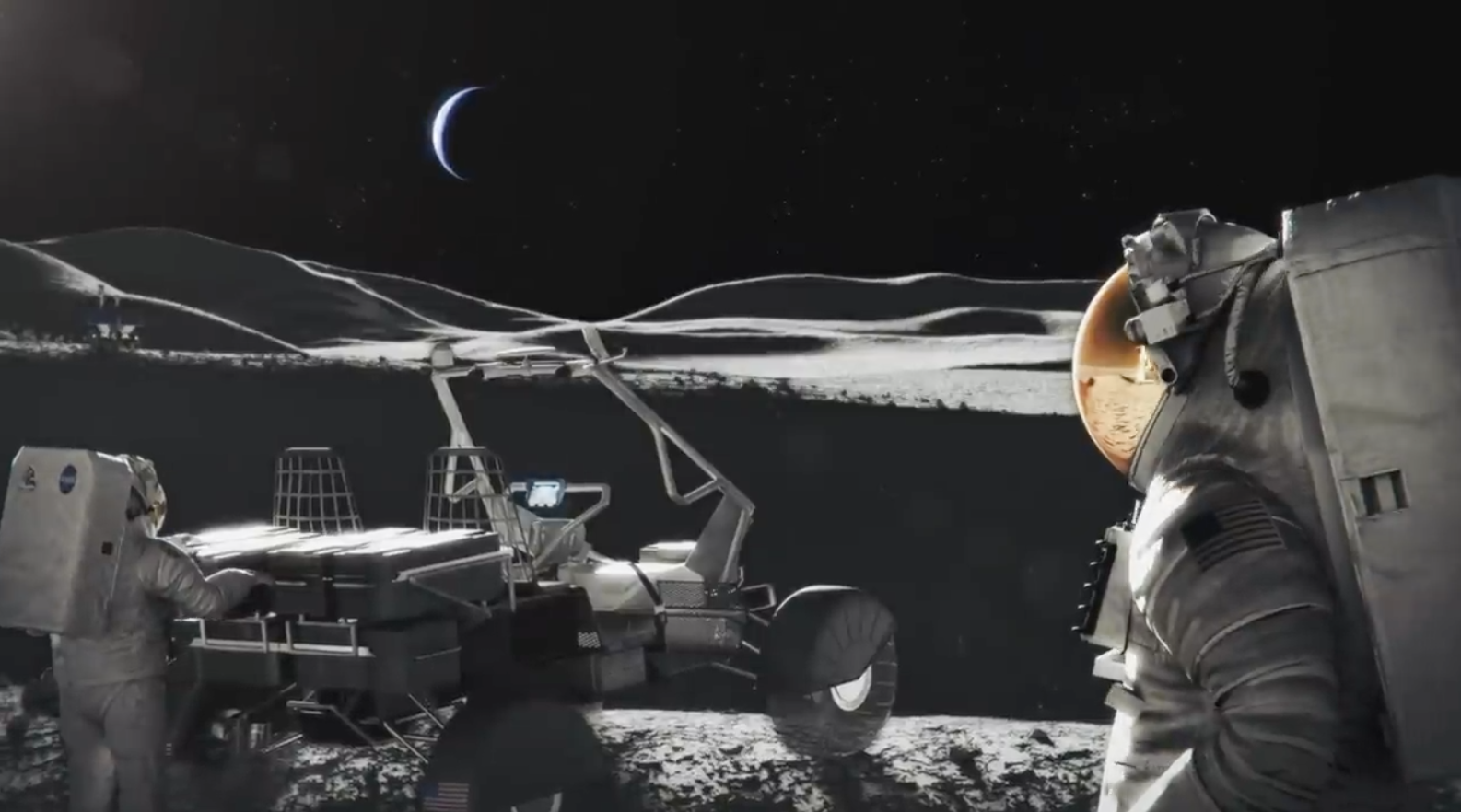

Democrats continue to support NASA and are committed to continuing space exploration and discovery. We believe in continuing the spirit of discovery that has animated NASA’s human space exploration, in addition to its scientific and medical research, technological innovation, and educational mission that allows us to better understand our own planet and place in the universe. We will strengthen support for the United States’ role in space through our continued presence on the International Space Station, working in partnership with the international community to continue scientific and medical innovation. We support NASA’s work to return Americans to the moon and go beyond to Mars, taking the next step in exploring our solar system. Democrats additionally support strengthening NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Earth observation missions to better understand how climate change is impacting our home planet.

From what we can gather, two major impending changes are likely.

First, a Biden administration could strengthen NASA and NOAA’s Earth-observing capabilities, with the goal of better understanding climate change. Lori Garver, the NASA deputy administrator during the Obama administration, was a key speaker at the SpaceVision 2020 convention on November 7 and 8, 2020. She said:

Managing the Earth’s ability to sustain human life and biodiversity will likely, in my view, dominate a civil space agenda for a Biden-Harris administration.

Second, although it supports a human return to the moon, a Biden administration has made no specific mention of launch dates. Launching humans to the moon in 2024 as part of the Artemis mission was the Trump administration’s timeline. There is speculation that the Biden administration will, at the very least, slow down the Artemis program, perhaps freeing up money for Earth science and other priorities elsewhere in the agency. On December 20, 2020, the United States government’s two houses of Congress agreed on NASA’s final budget for fiscal year 2021. In the report accompanying the bill, Senate appropriators noted that the looming uncertainty “makes it difficult to analyze the future impacts that funding the accelerated moon mission will have on NASA’s other important missions.” Wendy Whitman Cobb, associate professor of Strategy and Security Studies, U.S. Air Force School of Advanced Air and Space Studies, said

I don’t think Artemis will get canceled. I also don’t think it will get any more money than what it’s currently getting.

On November 10, the Biden administration announced the rosters of the agency review teams that will fan out across the federal government to gather information and guide the Biden administration’s planning. Garver, who led the Obama administration’s transition, commented:

The transition teams really come in to see how things are doing and make recommendations going forward.

A key priority of Biden’s space focus will be his selection of a new NASA administrator. He has so far been quiet about his choice, but there’s been plenty of speculation concerning potential candidates. That list is dominated by women. For example, Pam Melroy, a former NASA astronaut who flew on three shuttle missions, is a likely choice. Other possibilities include Wanda Austin, former president and chief executive of the Aerospace Corporation, and Gretchen McClain, a former NASA official who later worked in industry and serves on the boards of several companies.

Past transitions suggest that a new administrator for NASA might not come until months after the January 20 inauguration. After being inaugurated in January 2009, President Obama didn’t nominate Charlie Bolden as administrator (and Garver as deputy administrator) until May 2009; the Senate confirmed them in July. Bridenstine, despite emerging as a top candidate for NASA administrator days after Trump won the presidential election in November 2016, was only nominated in September 2017.

Bottom line: Democrat Joe Biden will be the next U.S. president. What are his plans for NASA and America’s space program? We predict a focus on Earth observation, especially that related to climate change. And we join many others in predicting that the goal of launching the next man and first woman to the moon in the Artemis program will be pushed back from 2024.

Read more from EarthSky: NASA announces 18 astronauts on its Artemis Team