Proposed step to help society prepare for a solar storm disaster

Solar scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder are pointing to a 2012 solar storm and its CME as an example, they say, of why society needs to prepare. Daniel Baker, director of CU-Boulder’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, gave a presentation on this subject to other scientists this week the annual American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco. Dr. Baker told EarthSky:

We would like space weather users, operators of systems, and policy makers adopt this event immediately and do war game scenarios with it.

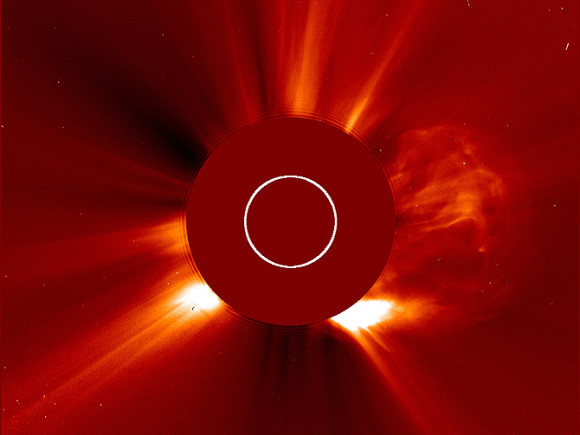

The event took place on July 23, 2012. It started with a giant storm that erupted on the sun, blasting material into space. Researchers clocked this coronal mass ejection, or CME – a giant bubble of gas and magnetic fields, containing some billion tons of charged solar particles – as traveling between 1,800 and 2,200 miles per second (about 3,000 km per second). It was one of the fastest CMEs on record, and the traveling cloud of solar particles narrowly missed Earth.

CMEs are common on the sun, especially when, as now, the sun is in an active phase of its 11-year cycle. When they occur, CMEs get blown off the sun in all directions. Most don’t come in Earth’s direction. But every so often, an eruption is aimed right at us. When that happens, a geomagnetic storm occurs. That’s when observers on Earth are likely see the beautiful aurora or northern lights. No matter how powerful the solar storm may have been, the event isn’t harmful to our human bodies on Earth, because our atmosphere protects us. But very powerful events have the potential to create a technological disaster by short-circuiting satellites, power grids, ground communication equipment and by threatening the health of astronauts and aircraft crews.

The most talked-about historical CME is probably the famous Carrington event of 1859. It was strong enough to have wreaked havoc on earthly technologies, if today’s technologies had existed at that time. During that event, the sun blasted Earth’s atmosphere hard enough that New Englanders could read their newspapers at night by aurora light.

The July 23, 2012 event on the sun was likely more powerful than the Carrington event of 1859, Baker said. It just wasn’t aimed our way.

But it might have been.

Baker said in a press release issued December 9:

My space weather colleagues believe that until we have an event that slams Earth and causes complete mayhem, policymakers are not going to pay attention. The message we are trying to convey is that we made direct measurements of the 2012 event and saw the full consequences without going through a direct hit on our planet.

We have proposed that the 2012 event be adopted as the best estimate of the worst case space weather scenario. We argue that this extreme event should be immediately employed by the space weather community to model severe space weather effects on technological systems such as the electrical power grid.

I liken it to war games – since we have the information about the event, let’s play it through our various models and see what happens. If we do this, we would be a significant step closer to providing policymakers with real-world, concrete kinds of information that can be used to explore what would happen to various technologies on Earth and in orbit rather than waiting to be clobbered by a direct hit.

Bottom line: Scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder would like policy makers to use the July 23, 2012 solar storm and its CME – which was measured by our spacecraft – in modeling responses to a similar CME that might be aimed our way.

Read more about C-U scientists’ thoughts on the need to prepare for powerful solar storms

More results from this week’s AGU meeting: