Twenty years after the Montreal Protocol, Antarctica’s ozone hole isn’t growing substantially larger each year, but it isn’t actually recovering – clearly growing smaller each year – yet, either. Atmospheric scientists reported that conclusion on December 11, 2013 to an audience of Earth scientists at the ” target=”_blank”>2013 American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco. These scientists presented results of two new studies, indicating that variations in temperature and winds drive year-to-year changes the size of the ozone hole. Susan Strahan of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland presented this work, saying:

Ozone holes with smaller areas and a larger total amount of ozone are not necessarily evidence of recovery attributable to the expected chlorine decline.

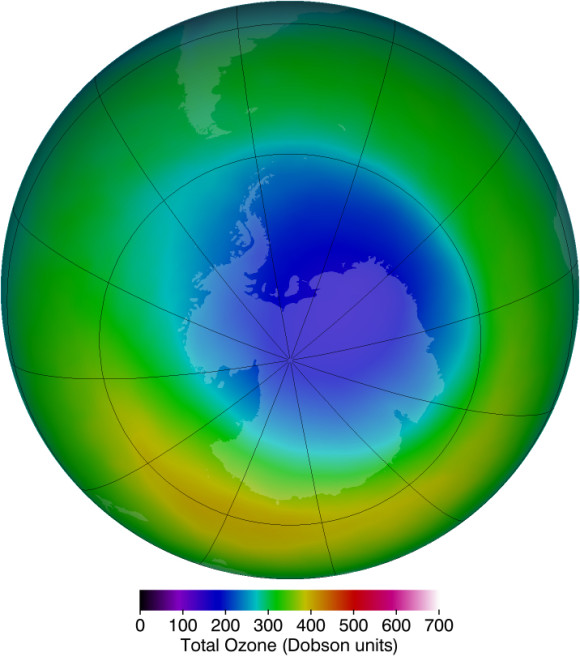

In the first study, Strahan and Natalya Kramarova, also of NASA Goddard, used satellite data to get a better look at the 2012 ozone hole, which was smaller than any ozone hole since 2002. They used satellite date to create a map showing how the amount of ozone differed with altitude throughout the stratosphere in the center of the 2012 ozone hole.

The map revealed more ozone at upper altitudes in early October, carried there by winds, above the ozone destruction in the lower stratosphere. The scientists concluded that:

… meteorology [not chemistry] was responsible for the increased ozone and resulting smaller hole, as ozone-depleting substances that year were still elevated.

This study has been submitted to the journal of Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics.

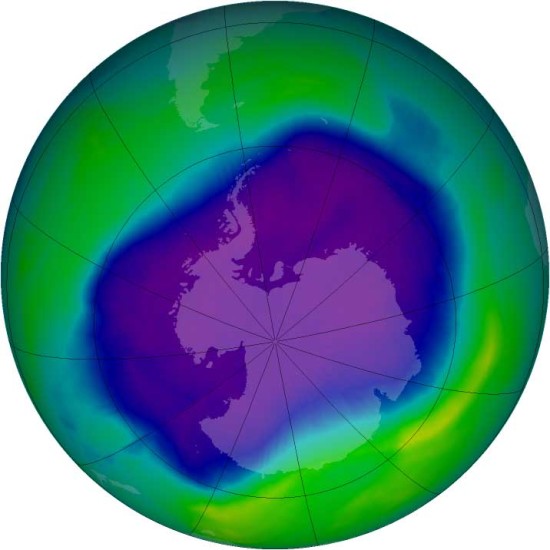

A second study – led by Strahan – looked at the ozone holes of 2006 and 2011 – two of the largest and deepest holes in the past decade. Her work showed that that, in 2011, there was less ozone destruction than in 2006 because the winds transported less ozone to the Antarctic – so there was less ozone to lose. Again, a meteorological – not chemical – effect.

In contrast, wind blew more ozone to the Antarctic in 2006 and thus there was more ozone destruction. This research has been submitted to the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

No one really knows how fast Earth’s ozone layer can be expected to recover, since the Montreal Protocol called for limiting emissions of ozone-depleting chemicals more than 20 years ago.

The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer went into effect on January 1, 1989. The treaty was hailed as an example of how countries can work together successfully toward an important goal. And Earth’s ozone layer is important. It’s what protects us from harmful UV rays from the sun. Still, there are many unknowns in trying to alter such a large-scale, human-made structure on Earth as an ozone hole.

The Antarctic ozone hole opens up each year in Southern Hemisphere winter. The ozone hole is typically most open in October. Since the Montreal Protocol, satellites have been monitoring the size of the annual ozone hole. They’ve watched the size of the hole change from year to year, sometimes smaller, sometimes larger.

The 2013 ozone hole was also slightly smaller than the average for recent decades, according to satellite data. The average size of the hole in September–October 2013 was 21.0 million square kilometers (8.1 million square miles). The average size since the mid 1990s is 22.5 million square kilometers (8.7 million square miles). Click here to read more about the 2013 ozone hole, which peaked in October.

Scientists have been watching for a clear trend in decreasing sizes for the Antarctic ozone hole. According to Susan Strahan and her colleagues, that has not yet begun to happen.

Read about the two new studies on Antarctic ozone, showing it is not yet in recovery.

More results from this week’s AGU meeting:

The weird object near Saturn’s A ring

Proposed step to help society prepare for a solar storm disaster