The latest tally for all known barrier islands world-wide is 2,149, a significant increase from a 2001 study that counted 1,492 islands. Scientists at Duke University and Meredith College painstakingly studied satellite images, topographic maps, and navigational charts to identify barrier islands across the world.

Their results have also raised new insights into the formation and dynamics of barrier islands, and demonstrated a need for further study to better predict how barrier islands will be impacted by climate and sea level changes during this century. Results of this survey, conducted by Matthew L. Stutz and Orrin H. Pilkey, were published in the March 2011 issue of Journal of Coastal Research.

Barrier islands are long narrow island chains made of sand and sediment. They’re found on all continents except Antarctica, with about 74 per cent of the islands in the northern hemisphere. The US has 405 barrier islands, more than any other country in the world.

The islands are dynamic; they’re built, eroded, and re-built by the actions of waves, tides, currents, and other physical ocean processes.

Following the coastline, these islands create a barrier between the mainland and open ocean, shielding low-lying coastal areas from the direct brunt of ocean storm damage and erosion. Protected waters between barrier islands and coastlines — bays, estuaries, and lagoons — serve as sanctuaries for many kinds of juvenile marine creatures. The barrier islands themselves also serve as important wildlife habitats.

Stutz, an assistant professor of geosciences at Meredith College, in Raleigh, North Carolina, noted in a press release that the 657 new barrier islands had long existed but were either overlooked or misclassified in past surveys.

For instance, it was thought that barrier islands could not form in places where seasonal tides exceeded 4 meters. However, in their new survey (that included the use of high-resolution satellite images), Stutz and Pilkey identified a chain of islands along the equatorial coast of Brazil. These islands had previously gone unnoticed because the lower resolution of past satellite images could not distinguish between mangroves and sand islands. In addition, no one looked for barrier islands there because spring tides reached as high as 7 meters, exceeding the 4 meter criteria established for barrier island formation. What scientists had not realized was that the sand needed to replenish the islands was so abundant that the supply was able to keep up with erosion caused by high spring tides. Those barrier islands turned out to be the longest chain in the world, 54 islands stretching 571 kilometers along the edges of mangrove forests, located south of the Amazon river mouth.

Stutz and Pilkey have suggested that their survey results indicate a need to develop new ways to study and classify barrier islands, taking into account geological and meteorological effects at local, regional, and global levels. This will be vital in understanding how significant climate and sea level changes, expected during this century, could affect barrier islands. Said Pilkey, in the same press release,

[The survey results] underscores the need to improve our understanding of the fundamental roles these factors have played historically in island evolution, in order to help us better predict future impacts. Barrier islands, especially in the temperate zone, are under tremendous development pressure, a rush to the oceanfront that ironically is timed to a period of rising sea levels and shoreline retreat.

A total of 2,149 barrier islands, 657 more than previously known, have been identified across the world, based on a survey of high-resolution satellite images, topographic maps, and navigational charts. Results of this survey by Matthew Stutz and Orrin Pilkey have underscored a need to revisit how barrier islands form and evolve, so that we can better understand how the islands will be impacted by temperature and sea level increases during this century.

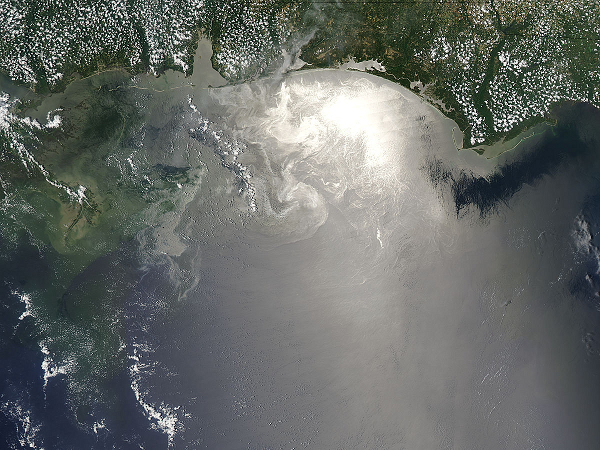

John Goff describes how Hurricane Ike eroded Gulf Coast islands