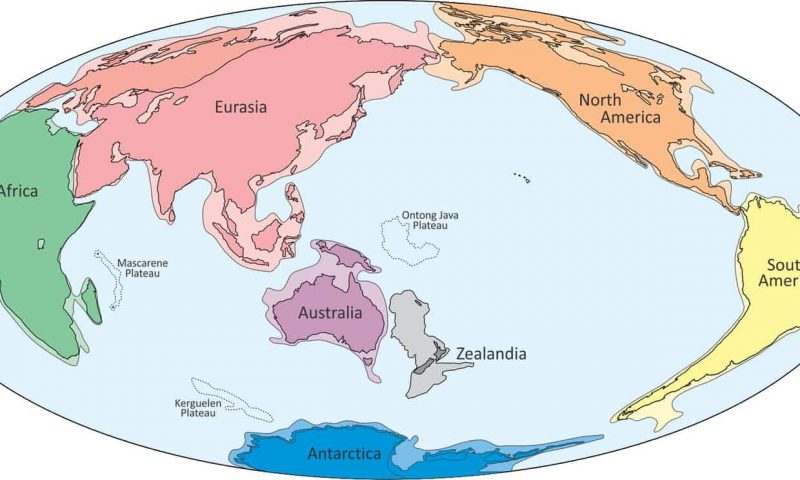

A team of 32 scientists from 12 countries returned last week from a nine-week voyage to study the once-lost continent of Zealandia in the South Pacific. This mostly submerged or hidden continent is an elevated part of the ocean floor, about two-thirds the size of Australia, located between New Zealand and New Caledonia. Scientists said earlier this year they thought Zealandia should be recognized as a full-fledged Earth continent. This was one of the first extensive surveys of the region, and the scientists who carried it out – affiliated with the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) at Texas A&M University – have just arrived back in Hobart, Tasmania, aboard the research vessel JOIDES Resolution. They said their work has already revealed that Zealandia might once have been much closer to land level than previously thought, providing pathways for animals and plants to cross between continents.

Little is known about Zealandia because it’s submerged about two-thirds of a miles (more than a kilometer) under the sea. Until now, the region has been sparsely surveyed and sampled.

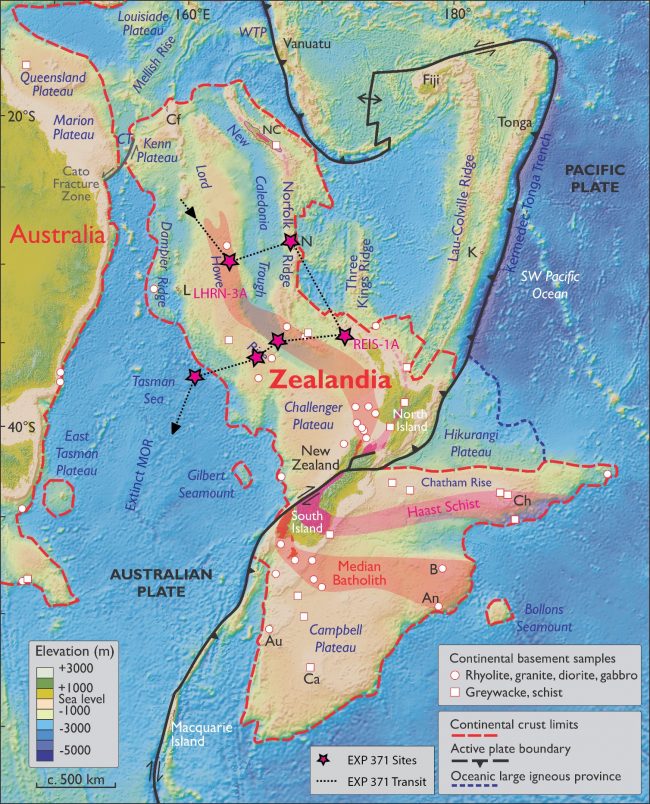

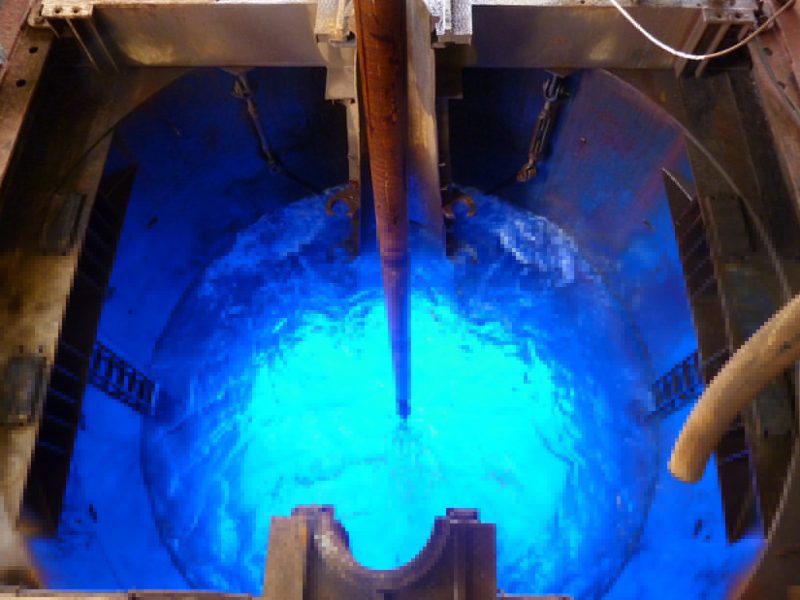

Scientists taking part in the 2017 expedition drilled deep into Zealandia’s seabed at six sites in water depths of more than 4,000 feet (1,250 meters). They collected 8,000 feet (2,500 meters) of sediment cores from layers that record how the geography, volcanism and climate of the region have changed over millions of years.

According to expedition co-chief scientist Gerald Dickens of Rice University in Houston, Texas, Zealandia expedition scientists made significant new fossil discoveries, proving that Zealandia was not always as deep beneath the waves as it is today. He said:

More than 8,000 specimens were studied, and several hundred fossil species were identified.

The discovery of microscopic shells of organisms that lived in warm shallow seas, and of spores and pollen from land plants, reveal that the geography and climate of Zealandia were dramatically different in the past.

He also said that the new discoveries show that the Pacific Ocean’s encircling Ring of Fire – where there are frequent earthquakes and powerful volcanic eruptions – had a role in causing Zealandia’s submersion beneath the ocean waves. That is, he said, the formation of the Ring of Fire caused dramatic changes in ocean depth and volcanic activity, which buckled the seabed of Zealandia.

Expedition co-chief scientist Rupert Sutherland of Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand said researchers had believed that Zealandia was submerged when it separated from Australia and Antarctica about 80 million years ago:

That is still probably accurate, but it is now clear that dramatic later events shaped the continent we explored on this voyage.

Big geographic changes across northern Zealandia, which is about the same size as India, have implications for understanding questions such as how plants and animals dispersed and evolved in the South Pacific.

The discovery of past land and shallow seas now provides an explanation. There were pathways for animals and plants to move along.

The sediment cores obtained during the expedition will be studied by scientists long after the expedition’s end. The scientists said they expect the cores to help them understand how Earth’s tectonic plates move and how the global climate system works.

These scientists also said that records of Zealandia’s history will provide a sensitive test for computer models used to predict future changes in climate.

Bottom line: An international team of scientists has just returned from the first major expedition to Zealandia, which some believed should be recognized as a full-fledged Earth continent, now submerged beneath the ocean in the South Pacific.