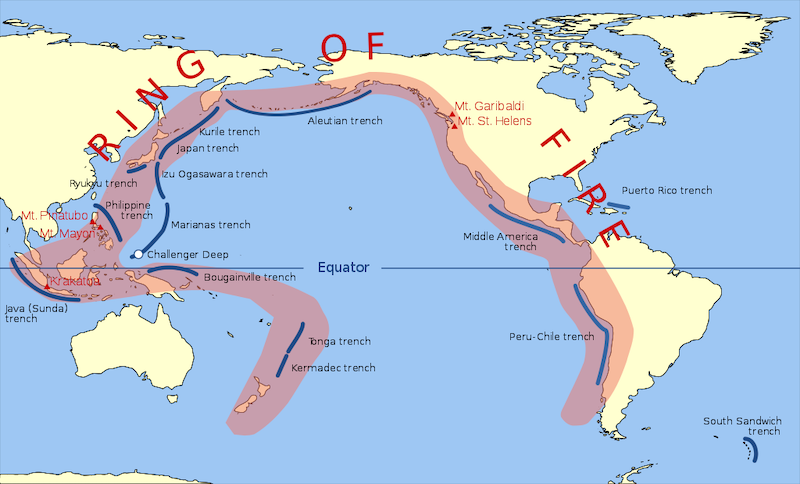

Most of Earth’s volcanoes and earthquakes occur in regions that skirt the Pacific Ocean, known as the Ring of Fire. It’s not really a ring, though, but more of a horseshoe-shaped swath – 24,900 miles (40,000 km) long – dotted with seismically active locations.

If you could view it from space, the Ring of Fire would appear as a strip that runs up the western coasts of South America and North America, continuing across the Alaskan Aleutian Islands to Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula. Then, it heads south, off the coast of Eastern Asia, passing through Japan. At Southeast Asia, it jogs eastward through the Indonesian islands of Sumatra and Java, past Papua New Guinea, then southward again to New Zealand.

Volcanoes

Geologists have found evidence of nearly 1,000 prehistoric volcanoes active along the Ring of Fire in the past 12,000 years. The January 15, 2002, Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai eruption occurred on the Ring of Fire. It was the largest explosion recorded in the atmosphere by modern instrumentation. It blasted winds to the edge of space and may weaken the ozone layer.

Some other memorable volcanic eruptions along the Ring of Fire include the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines. Pinatubo’s eruption caused global cooling for about a year. And in the United States, the 1980 Mount St. Helen eruption resulted in the collapse of half the mountainside. It was the most significant volcanic eruption in U.S. history, causing the death of 57 people. The explosion obliterated the surrounding 230 square miles in minutes.

In 2022, Netflix came out with a documentary called The Volcano: Rescue from Whakaari. The documentary heartbreakingly recounts the 2019 eruption of Whakaari (White Island) in New Zealand. There were 47 tourists and tour guides on the island when the volcano suddenly erupted, ultimately killing 22.

But volcanic activity along the Ring of Fire also births new land. For example, a young volcano is making itself known off the coast of Japan. The Nishinoshima volcano has been growing since 2013 and underwent a growth spurt in June 2020.

Earthquakes

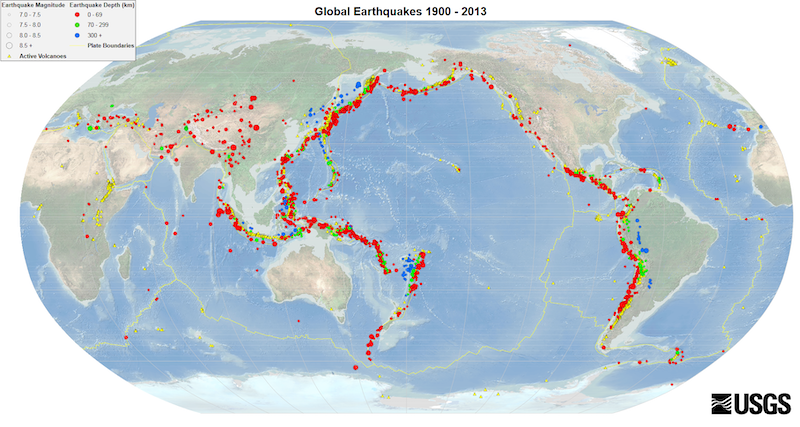

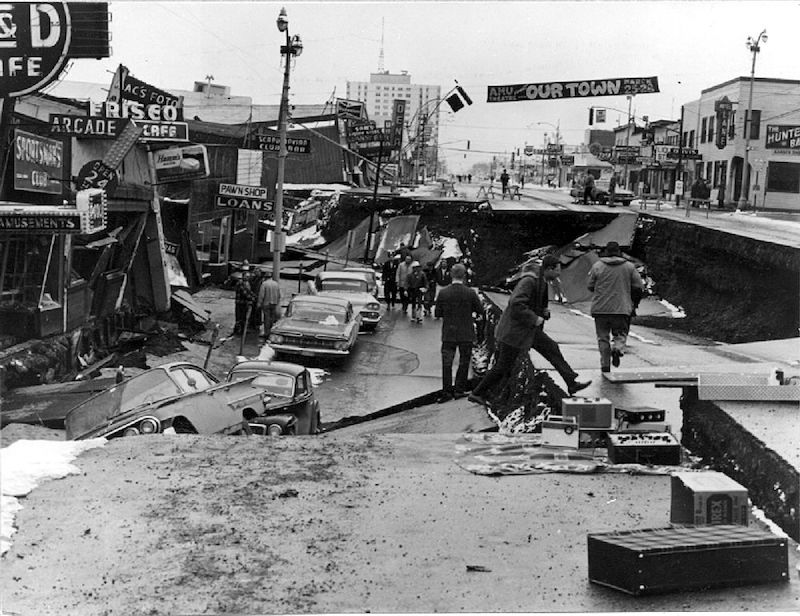

About 90% of all earthquakes, and 80% of the largest ones, occur in the Ring of Fire. Since the invention of equipment to measure earthquake intensity in the 1930s, four of the most powerful earthquakes have occurred in the Ring of Fire. In 1952, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck the Kamchatka Peninsula of Russia. Chile’s Valdivia earthquake in 1960 was a stunning 9.4 to 9.6 on the Richter scale. Four years later, a magnitude 9.2 earthquake hit Alaska.

And, more recently, the 2011 9.1-magnitude earthquake Tohoku Earthquake in Japan has become seared in our memories. The world watched, horrified, as large stretches of coastal land and communities near Sendai, Japan, became engulfed in a tsunami triggered by an offshore earthquake. It caused widespread death and destruction and lead to the serious breach of a nuclear reactor. More than 18,000 people died.

Why is the Ring of Fire so seismically active?

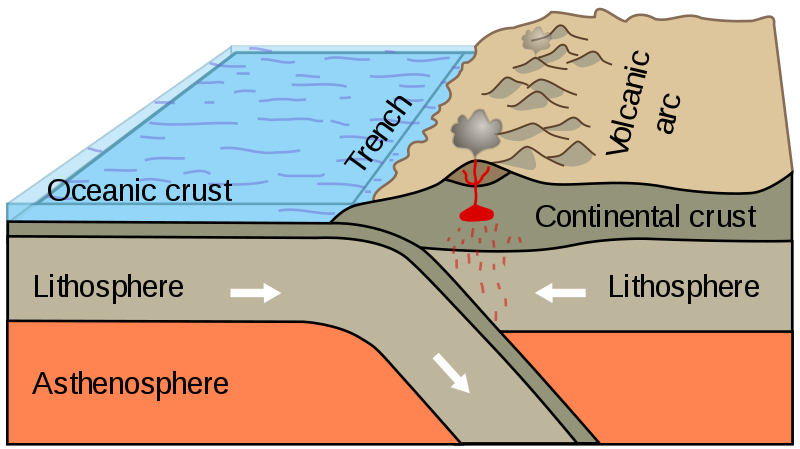

Volcanoes and earthquakes most often occur along the borders of tectonic plates. These plates are layers of the Earth’s crust that float – moving very slowly – on molten rock in Earth’s mantle.

The Ring of Fire is not a single geological feature. In actuality, it’s separate adjoining features caused by interactions of several different tectonic plates. Where the two plates meet – in a subduction zone – the heavier plate sinks below the lighter plate and melts in the Earth’s molten mantle.

There are several plates causing seismic activity along the Ring of Fire. In most locations, the plates are colliding, causing subduction zones. (An exception: in a section of western North America, the plates are rubbing against each other laterally. This builds up tension that occasionally releases as earthquakes.)

Some of these subduction zones are also in the deepest parts of the ocean. The Marianas Trench, 36,037 feet (10,984 m) – that’s 6.8 miles (11 km) – below sea level at its deepest known point, is in a subduction zone.

When tension from a bending plate releases, earthquakes happen. At some locations, molten rock is able to infiltrate through the crust to create volcanoes. Most of these seismic activities happen undersea.

Bottom line: The Ring of Fire is home to the majority of Earth’s volcanoes and earthquakes. This region rings the Pacific Ocean where tectonic plates interact.