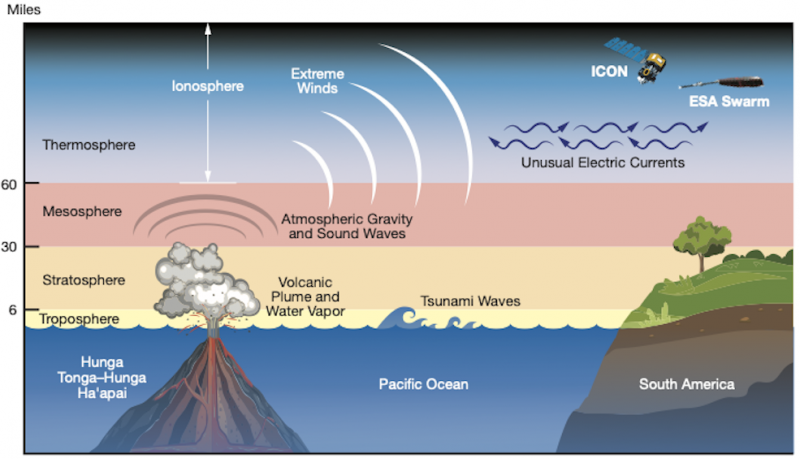

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption on January 15, 2022, sent shock waves rippling through Earth’s oceans and atmosphere. Its massive global effects will go down in history, scientists said. They said Tonga’s eruption dwarfed the biggest nuclear detonations yet conducted. And this month they said that – in the hours after the eruption – the blast from the Tonga volcano caused greater-than-hurricane-speed winds and unusual electric currents to form high in Earth’s atmosphere, in the layer we call the ionosphere.

The Karman line – at an altitude of 62 miles or 100 km – is a way of defining a boundary between Earth’s atmosphere and outer space. Tonga’s effects caused winds that were measured by satellites at nearly twice the height of the Karman line above Earth’s surface, at altitudes of up to 120 miles (190 km).

Meanwhile, on Earth, when a storm’s maximum sustained winds reach 74 mph (120 kph), we call it a hurricane. In 2015, Hurricane Patricia attained the strongest 1-minute sustained winds on record at 215 mph (345 kph). The wind speeds created by the Tonga volcano were more than twice as high, measured by satellites at up to 450 mph (720 kph).

Tonga volcano space disturbances

Brian Harding, a physicist at University of California, Berkeley, is lead author on a new paper about the findings, which was published on May 10, in the peer-reviewed journal Geophysical Research Letters. He said in a statement:

The volcano created one of the largest disturbances in space we’ve seen in the modern era. It’s allowing us to test the poorly understood connection between the lower atmosphere and space.

In other words, these scientists are finding out that earthly events – taking place in the lowest layer of our atmosphere, called the troposphere, and extending up to only about 6 miles (10 km) – can affect space. Jim Spann, space weather lead for NASA’s Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., commented in the scientists’ statement:

These results are an exciting look at how events on Earth can affect weather in space, in addition to space weather affecting Earth. Understanding space weather holistically will ultimately help us mitigate its effects on society.

Earth’s lower atmosphere connects to space

NASA’s ICON mission launched in 2019 to identify how Earth’s weather interacts with weather from space. The scientists explained this idea is relatively new and:

… [Supplants] previous assumptions that only forces from the sun and space could create weather at the edge of the ionosphere. In January 2022, as the spacecraft passed over South America, it observed one such earthly disturbance in the ionosphere triggered by the South Pacific volcano.

When the volcano erupted, it pushed a giant plume of gases, water vapor, and dust into the sky. The explosion also created large pressure disturbances in the atmosphere, leading to strong winds. As the winds expanded upwards into thinner atmospheric layers, they began moving faster. Upon reaching the ionosphere and the edge of space, ICON clocked the windspeeds at up to 450 mph (724 kph) – making them the strongest winds below 120 miles (193 km) altitude measured by the mission since its launch.

Electrojet changed its direction

The European Space Agency’s Swarm mission also saw some of Tonga’s effects on the high atmosphere. Swarm is a three-satellite Swarm mission dedicated to unravelling mysteries of Earth’s magnetic field. The scientists’ statement explained:

In the ionosphere, the extreme winds also affected electric currents. Particles in the ionosphere regularly form an east-flowing electric current – called the equatorial electrojet – powered by winds in the lower atmosphere.

After the eruption, the equatorial electrojet surged to five times its normal peak power and dramatically flipped direction, flowing westward for a short period.

Joanne Wu, a physicist at University of California, Berkeley, and co-author on the new study, concluded:

It’s very surprising to see the electrojet be greatly reversed by something that happened on Earth’s surface.

Bottom line: After analyzing satellite data, scientists found that – in the hours after the Tonga volcano erupted – hurricane-speed winds and unusual electric currents formed in Earth’s ionosphere, the electrified upper layer of our atmosphere, at the edge of space.