One of the “coolest” science papers to be published in 2014 was this summer’s announcement in the journal Nature that diverse microbes are thriving in a subglacial lake deep beneath the Antarctic ice sheet. Nearly 4,000 species of microorganisms were found in the cold, dark waters of Lake Whillans, which sits about half a mile below the surface of the ice. The presence of microbes in one of Earth’s harshest environments could have implications for discovering life elsewhere in the solar system.

On January 27, 2013, a research team led by John Priscu of Montana State University drilled successfully through 800 meters of ice (0.5 miles) to reach the waters of Lake Whillans, where they retrieved pristine samples of water and sediment. They used a hot water drilling system that was equipped with disinfectants, ultraviolet radiation, and filtration technologies to ensure that the samples were free of contamination. Samples of water and sediment were brought back to the laboratory and analyzed for the presence of microorganisms.

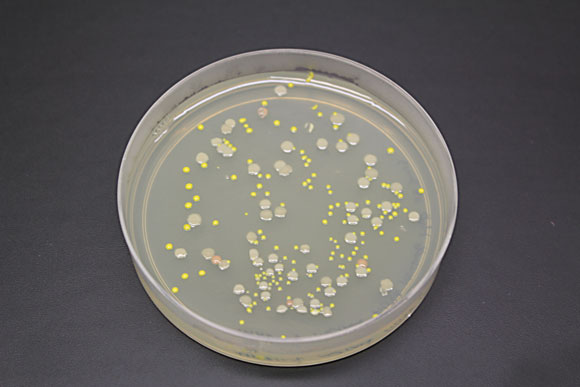

Back in the laboratory, scientists isolated the genetic material (ribosomal RNA gene sequences) and detected nearly 4,000 species of bacteria in the water and almost 2,500 species of bacteria in the sediment. Not only was the number of species high, but the total number of bacterial cells in the water was high too—the density amounted to 130,000 cells per milliliter of water. Other tests confirmed that these microorganisms were metabolically active.

The findings were published in the journal Nature on August 21, 2014. Brent Christner, lead author of the new study, is a microbiologist at Louisiana State University. He commented on the high cell counts in a news article:

I think we were all surprised by that number. We’ve got lakes here on campus that we can take samples of and the numbers are about in that range.

Unlike microbial communities in sunlit lakes, which are fueled by photosynthesis, microbial communities in deep, dark waters are fueled by chemosynthetic processes. Indeed, many of the bacterial species detected in Lake Whillan appear to be similar to known chemoautotrophs that use iron, nitrogen, or sulfur compounds as energy sources.

Subglacial lakes in Antarctica consist of water that has melted from the underside of the ice sheet. Despite the frigid temperatures, melt water is produced at depth by heat supplied through geothermal energy and friction from ice flows. Since the 1990s, scientists have discovered about 400 subglacial lakes in Antarctica with the use of ice-penetrating radar technologies. Studies on other Antarctic subglacial lakes are being planned for the future.

The new findings also hint at where to look for life elsewhere in our solar system. Both Saturn’s moon Enceladus and Jupiter’s moon Europa are believed to have thick crusts of ice that sit on top of liquid oceans.

John Priscu, co-author of the new study, said:

Europa has an icy shelf and liquid water beneath it, just like we find in the Antarctic system, which allows us to draw some conclusions about what we might find there. I’d love to be around when we finally penetrate that environment to look for life.

Other authors of the new study published in Nature include Amanda Achberger, Carlo Barbante, Sasha Carter, Knut Christianson, Alexander Michaud, Jill Mikucki, Andrew Mitchell, Mark Skidmore, Trista Vick-Majors, and the WISSARD Science Team.

Funding for the project was provided by the National Science Foundation, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration, Montana’s Space Grant Consortium, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the Italian National Antarctic Program.

Bottom line: A diverse and metabolically active microbial ecosystem was found thriving in Lake Whillan, a subglacial lake in Antarctica that is located half a mile beneath the ice sheet. The new findings were published in the journal Nature on August 21, 2014.

Microbes on or within Saturn’s moon Enceladus?

Unique microbes discovered in one of Earth’s harshest landscapes