What to know before buying a telescope

Before you buy, ask yourself this question. Can you identify a few bright planets, and some bright stars and constellations? Buying a telescope is one thing; learning where and how to aim it is another. It’s fun to spend a year coming to know the stars and planets as they shift across Earth’s seasons. Do you need a telescope for that? Would binoculars be better?

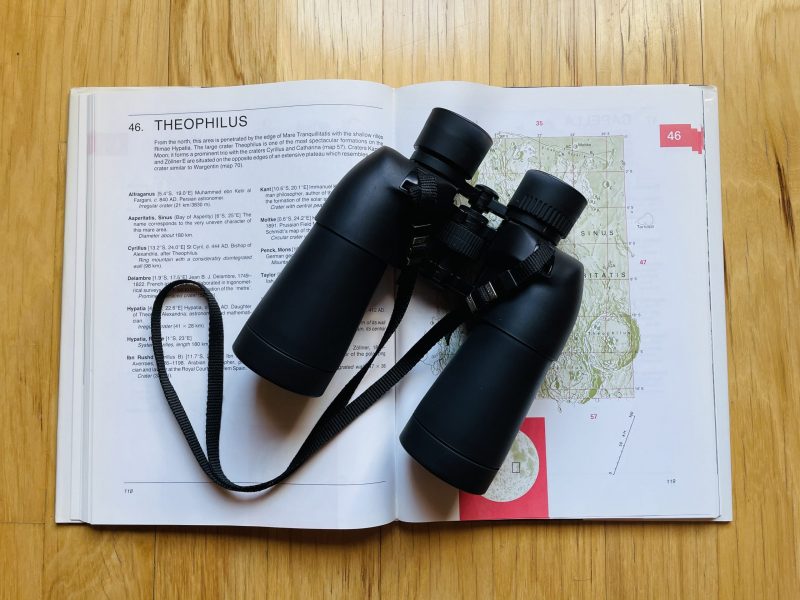

It’s the wise beginner who spends a year with some simple star charts or a planisphere – and maybe a pair of binoculars – before investing in a telescope.

First binoculars for stargazing

The pro for binoculars is their ease of use. Most of us have already held and pointed binoculars at distant objects. For the beginning stargazer, a pair of 7×35, 8×40 or 7×50 binoculars is probably your best choice.

The first number tells you the binoculars’ strength (magnification power) and the second the diameter of the objective lens, in millimeters. Binoculars can be used for stargazing up to a magnification of 10 without the support of a tripod. They won’t show you meaningful detail on the planets, but they’ll bring out some detail on the moon, let you glimpse some of Jupiter’s moons and enhance the colors and brightnesses of sky objects. Binoculars are particularly useful for deep-sky observing of star clusters, nebulae and galaxies.

The con for binoculars is that, because they work so well for beginning deep-sky observing, stargazers enjoy them most when they have regular access to darker skies. What’s more, binoculars use complicated optics based on internal prisms that work to provide an erect image. With time – maybe a few years – the prisms may lose their factory-set alignment. Plus, in humid climates both the prisms and the lenses may start developing mold.

Luckily, binoculars are a smaller financial investment than telescopes. A reasonable budget for beginners can range from about $100 and $200. Of course, you can spend more.

Read more: Top tips for binocular stargazing

Buying a beginner’s telescope

Once you know some bright stars and constellations, you’re ready to consider buying a telescope. Telescopes are either refractors (using lenses) or reflectors (using mirrors). Both are excellent.

If you want a refractor, consider a 3- to 4-inch (75- to 100-millimeter) long-tube achromatic refractor. Don’t confuse an achromatic refractor with an apochromatic. Those two seemingly inconspicuous letters can make a huge difference in cost.

If you want a reflector, consider a 6- to 8-inch (150- to 200-millimeter) with a Dobsonian mounting. This type of mounting was popularized by John Dobson in the 1960s. It’s easy to use and more portable than classical equatorial mounts. It is also cost-effective, giving you the best possible optical quality for the least money. Note, however, that Dobsonian mounts don’t use clock drives. To compensate for Earth’s spin, you have to “nudge” the telescope every few minutes along both axes to keep an object in view.

If your primary goal is astrophotography, you’ll need an equatorial mount and a clock drive. On the other hand, if you want a solid first telescope for learning the sky, a Dobsonian mount is for you. The budget for a beginner’s Dobsonian might range from $300 to $600. As always, you can spend more.

6 tips for 1st-telescope buyers

1. A beginner should be concerned more with aperture (tube diameter) than with magnifying power. The primary purpose of an astronomical telescope is to collect light; its magnifying power is a by-product. For example, a 6-inch (150-mm) telescope has twice the diameter of a 3-inch (75-mm) unit, meaning that its optical surface will be four times larger. In turn, this tells us that the 6-inch instrument will gather four times as much light as the 3-inch, making it four times more powerful. Given equal optical quality, a larger aperture is preferable, if the budget allows.

2. Consider who will use the telescope, and how. Telescopes are big and bulky, requiring setup each time. Purchase a telescope that is manageable for the person who will be using it. Children and older stargazers, in particular, might get more use out of smaller, lighter instruments.

3. Spend a year just observing, and not taking pictures. Learning to see fine detail on planets and the moon, and in the vast array of objects in the deep sky, is an art. With practice, your eyes will learn to see. Budding astronomers will benefit from putting lots of time at the eyepiece. So, a first telescope should be optimized for visual astronomy and not photography.

4. Consider what else you need for an observing session. Many stargazers bring along lawn chairs, perhaps a small table to spread out your charts, a thermos of coffee, sandwiches. And, of course, you will need a red flashlight in order to read your charts without ruining your night vision.

5. Keep your expectations reasonable. A planet will not appear through your eyepiece as it looks on your wall poster! Also, forget about colorful nebulae. Light collected by a telescope is seen differently by cameras versus the human eye. All of that said, if you patiently train your eye to see – and allow yourself some visits to dark-sky locations – you might find yourself falling in love with the silence, the night air, and the wonder of peering upward, through a telescope, at the universe’s marvels.

6. Connect with other amateur astronomers. Get in touch with your local astronomy club. Take a peek through the eyepiece of every telescope you encounter. Speak to the owners and ask them about the pros and cons. They’ll love to tell you about it. In this way, you can become familiar ahead of time with the basic setup and operation of an astronomical instrument. To find a group near you worldwide, visit this list at Skyandtelescope.com. For the U.S., visit this list from NASA.

Good luck and have fun!

Bottom line: Binoculars are excellent for learning the sky, providing good views of the solar system and deep sky objects for beginners. When you finally decide to buy your first-ever telescope, keep it simple! A telescope that is easy to set up, use and repair is key to a solid beginning in amateur astronomy.