Earth farthest from sun

Planet Earth reached aphelion – when Earth was farthest from the sun – at 5 UTC today (12 a.m. CDT on July 5, 2024). At that time, Earth was 94,510,538 miles (152,099,968 km) from the sun. It’s been a hot summer already in parts of the Northern Hemisphere. And Earth’s aphelion always comes in July, in the midst of Northern Hemisphere summer (and Southern Hemisphere winter). So you know our distance from the sun doesn’t cause Earth’s seasons.

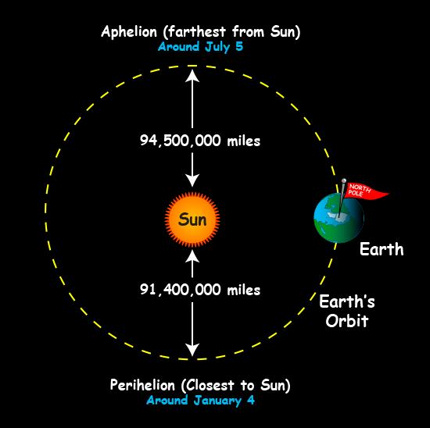

Why does our distance from the sun change? It’s because Earth’s orbit is almost, but not quite, circular. Our distance from the sun doesn’t change much, percentage-wise (a little over 3%). So today (July 5), we’re about three million miles (five million km) farther from the sun than we will be six months from now. That’s in contrast to our average distance from the sun of about 93 million miles (150 million km).

By the way, the word aphelion comes from the Greek words apo meaning away, off, apart and helios, for the Greek god of the sun. Apart from the sun. That’s us, in early July. But we’re not much farther apart than usual. See the diagram below.

What causes the seasons?

The seasons aren’t due to Earth’s changing distance from the sun. In fact, we’re always farthest from the sun in early July during northern summer and closest in January during northern winter.

Instead, the seasons result from Earth’s tilt on its axis. Right now, it’s summer in the Northern Hemisphere because the northern part of Earth is tilted most toward the sun. We’re receiving the sun’s rays most directly

Meanwhile, it’s winter in the Southern Hemisphere because the southern part of Earth is tilted most away from the sun. The more indirect sunlight causes cooler temperatures.

Read more: Why Earth has 4 seasons

Earth’s varying distance from the sun does affect the length of the seasons, though. That’s because, at our farthest from the sun, like now, Earth is traveling most slowly in its orbit. Consequently, that makes summer the longest season in the Northern Hemisphere and winter the longest season on the southern half of the globe.

Conversely, winter is the shortest season in the Northern Hemisphere, and summer is the shortest in the Southern Hemisphere, in each instance by nearly five days.

Earth at perihelion and aphelion 2001 to 2100

Closest and farthest points tied to solstices?

The short answer is no. It’s true that Earth is farthest from the sun every year in early July, about two weeks after the June solstice. And it’s true that Earth is closest to the sun every year in early January, about two weeks after the December solstice. Is it a coincidence? Yes, it is. Over the long course of time, the dates of Earth’s closest and farthest points to the sun shift with respect to the solstices.

According to timeanddate.com:

Due to variations in the eccentricity of the Earth’s orbit, the dates when the Earth reaches its perihelion or aphelion are not fixed. In 1246, the December solstice was on the same day as the Earth reached its perihelion. Since then, the perihelion and aphelion dates have drifted by a day every 58 years. In the short term, the dates can vary up to two days from one year to another.

Mathematicians and astronomers estimate that in 6430, over 4000 years from now, the perihelion will coincide with the March equinox.

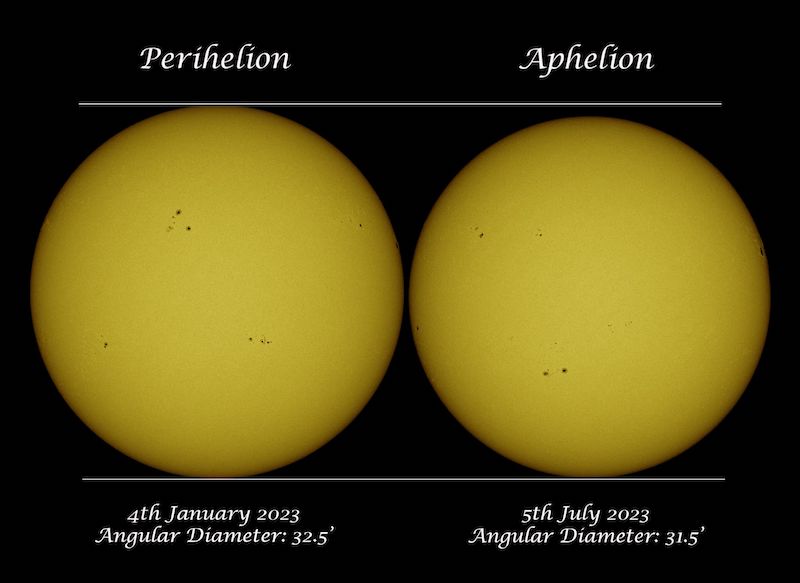

Visual size difference when Earth farthest from sun

Bottom line: Planet Earth reaches its most distant point from the sun for 2024 on July 5. Astronomers call this yearly point in Earth’s orbit our aphelion.

EarthSky astronomy kits are perfect for beginners. Order yours today.