Comet Halley visited last in 1986

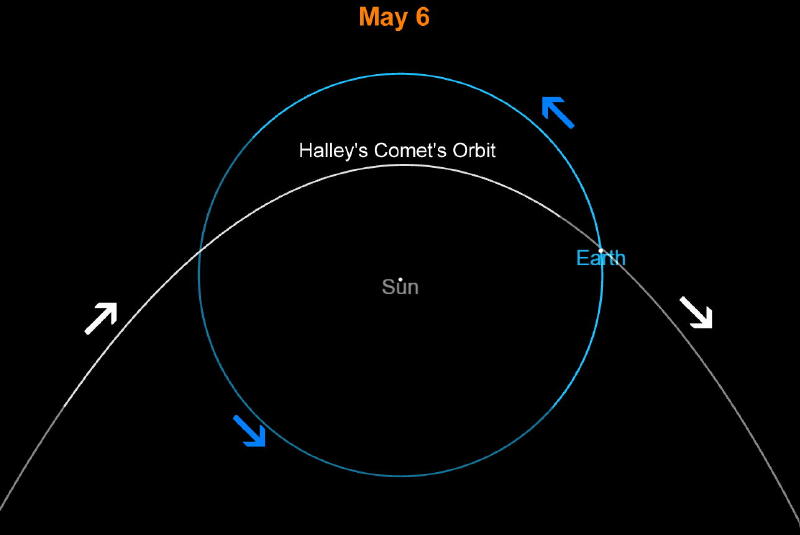

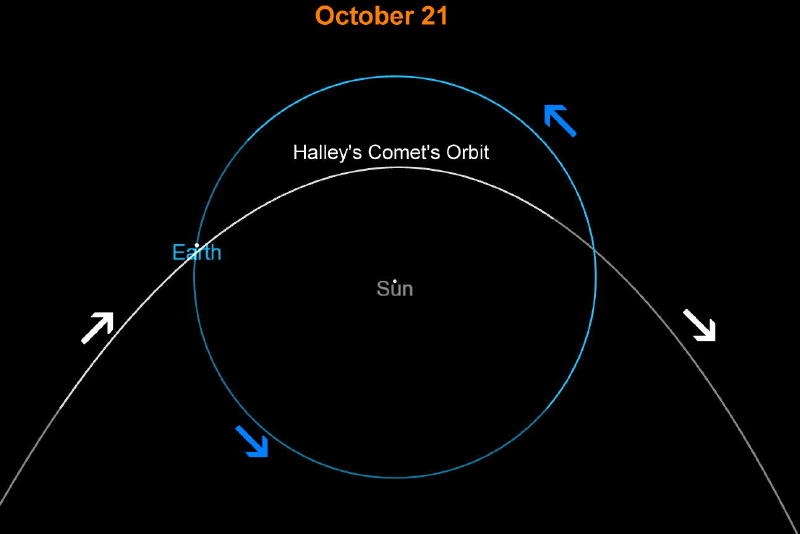

The famous comet 1P/Halley – aka Halley’s Comet – swings into the inner solar system about every 76 years. At such times, the sun’s heat causes the comet to loose its icy grip over its mountain-sized conglomeration of ice, dust, and gas. And so, at each pass, the crumbly comet sheds a fresh trail of debris into its orbital stream. It lost about 1/1,000th of its mass during its last flyby, in 1986. And it so happens we intersect Comet Halley’s orbit not once, but twice each year. That’s why – although the comet itself is nowhere near – Halley’s Comet is the parent of not just one, but two well-known annual meteor showers, one in May and one in October.

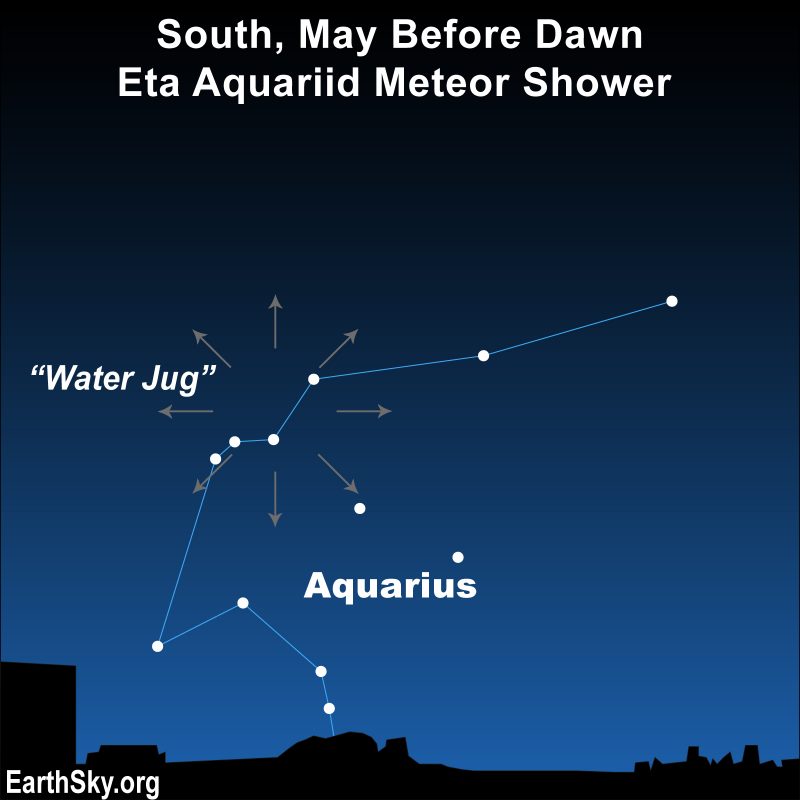

In early May, we see bits of this comet as the annual Eta Aquariid meteor shower.

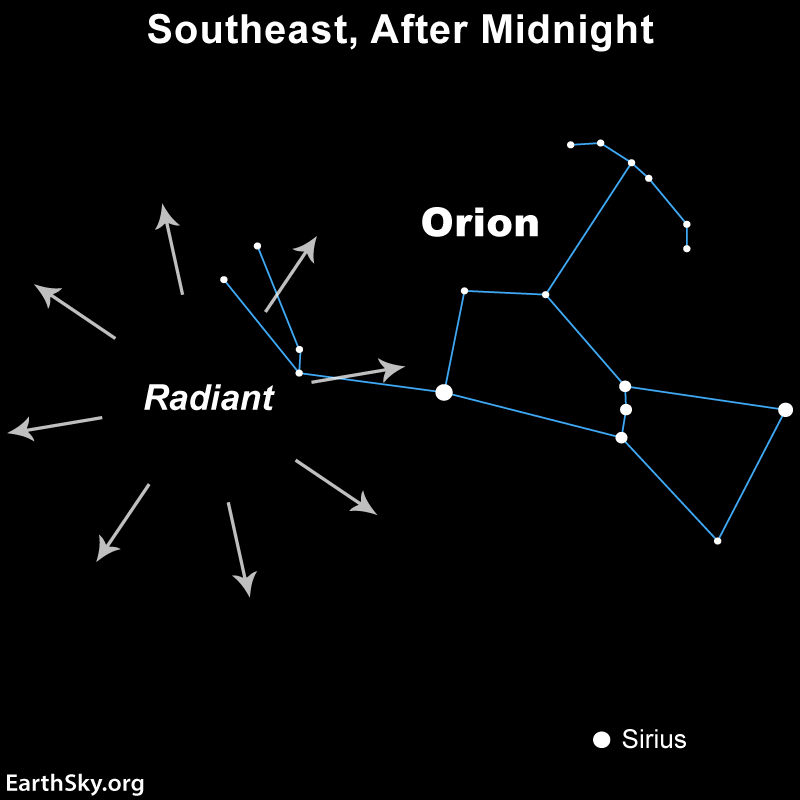

Then some six months later, in October, Earth in its orbit again intersects the orbital path of Comet Halley. This time around, these broken-up chunks from the comet burn up in Earth’s atmosphere as the annual Orionid meteor shower.

And, by the way, Halley is pronounced like valley. According to Ian Ridpath:

Many people nowadays say “Hailey”, a legacy of the 1950s rock group Bill Haley and the Comets.

Comet debris litters Comet Halley’s orbit

Because Halley’s Comet has circled the sun innumerable times over countless millennia, cometary fragments litter its orbit. That’s why the comet doesn’t need to be anywhere near the Earth or the sun in order to produce a meteor shower. Instead, whenever our Earth in its orbit intersects Comet Halley’s orbit, cometary bits and pieces – often no larger than grains of sand or granules of gravel – smash into Earth’s upper atmosphere, to vaporize as fiery streaks across our sky: meteors.

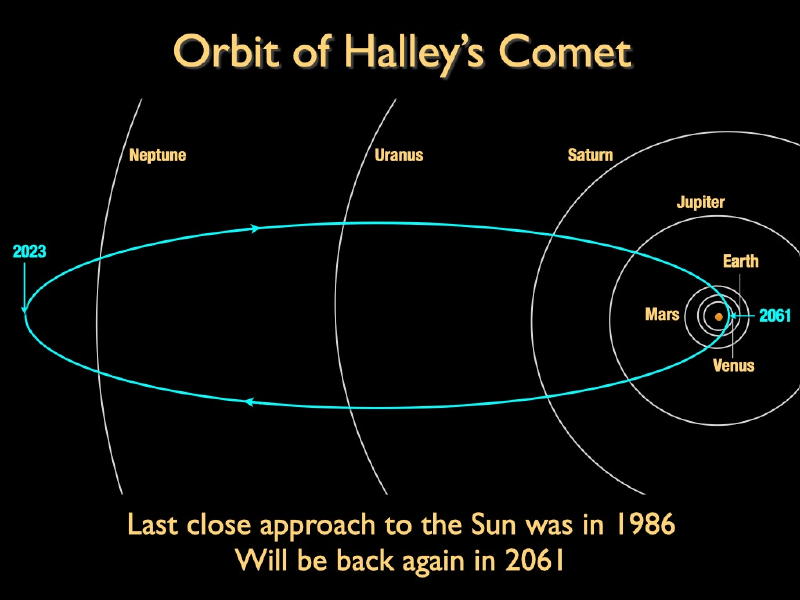

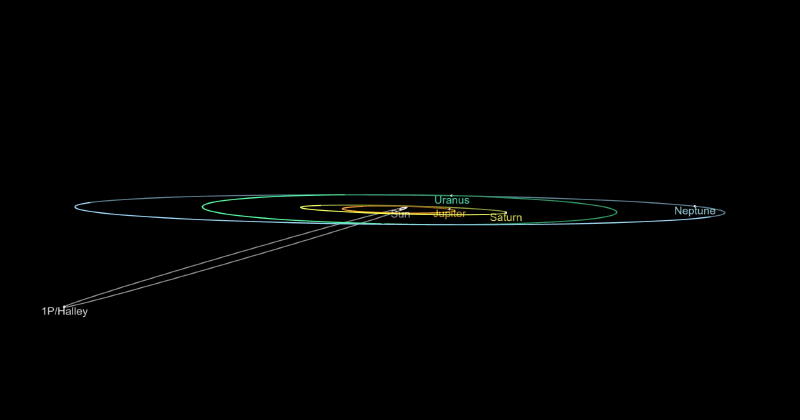

The diagrams below can help you visualize Earth’s orbit with respect to the path of Halley’s Comet.

Where is Comet Halley now?

Often, astronomers like to give distances of solar system objects in terms of astronomical units (AU), which is the sun-Earth distance. Halley’s Comet lodges 0.587 AU from the sun at its closest point to the sun (perihelion) and 35.3 AU at its farthest point (aphelion).

In other words, at its farthest, Halley’s Comet resides about 60 times farther from the sun than it does at its closest.

It was last at perihelion in 1986, and will again return to perihelion in 2061.

In December of 2023, the comet reached its farthest point from the sun that binds it in orbit. Then – pulled inexorably by the sun’s gravity – it curved around and is heading back toward the inner solar system again. Comet Halley will be back in 2061.

So the comet is far away. Even so, meteoroids – bits of debris left behind in the comet’s orbit – swim throughout Halley’s Comet’s orbital stream. So each time Earth crosses the orbit of the comet, in May and October, these meteoroids turn into incandescent meteors once they plunge into the Earth’s upper atmosphere.

Meteor showers and comets

Of course, Halley’s Comet isn’t the only comet that produces a major meteor shower …

Three of the comets in the table below are each responsible for two meteor showers. We’ve already discussed Halley’s Comet. The asteroid 2004 TG10, responsible for the Northern Taurids, is part of the Taurid Complex, which includes Comet Encke, itself producing the Southern Taurids. And, asteroid 2003 EH1, responsible for the Quadrantids appears to be part of the Machholz Complex, which also includes Comet 96P/Machholz, itself producing the Delta Aquariids.

| Meteor Shower | Parent Comet | Peak Date | Orbital Period | Perihelion | Aphelion |

| Quadrantids | 2003 EH1 (asteroid | Jan 4 | 5.52 yrs | 1.19 AU | 5.06 AU |

| Lyrids | Comet Thatcher (1861 G1) | Apr 23 | 413 yrs | 0.92 AU | 110 AU |

| Eta Aquariids | Comet 1P/Halley | May 6 | 75.3 yrs | 0.59 AU | 35.3 AU |

| Delta Aquariids | Comet 96P/Machholz | July 30 | 5.28 yrs | 0.12 AU | 5.94 AU |

| Perseids | Comete 109P/Swift-Tuttle | Aug 13 | 133 yrs | 0.96 AU | 51.2 AU |

| Draconids | Comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner | Oct 8 | 6.62 yrs | 1.04 AU | 6.01 AU |

| Orionids | Comet 1P/Halley | Oct 21 | 75.3 yrs | 0.59 AU | 35.3 AU |

| S Taurids | Comet 2P/Encke | Nov 6 | 3.30 yrs | 0.33 AU | 4.11 AU |

| N Taurids | 2004 TG10 (asteroid) | Nov 13 | 3.34 AU | 0.31 AU | 4.16 AU |

| Leonids | Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle | Nov 17 | 33.2 yrs | 0.98 AU | 19.69 AU |

| Geminids | 3200 Phaethon (asteroid) | Dec 14 | 1.43 yrs | 0.14 AU | 2.40 AU |

| Ursids | Comet 8P/Tuttle | Dec 22 | 13.6 yrs | 1.03 AU | 10.38 AU |

What are those asteroids doing here?

Until recently a comet was a comet, and an asteroid was an asteroid. But the more we have learned about abut them the more the lines between them became blurred. The long-held belief that meteor showers can come only from active comets has been challenged by the discovery of asteroids being the parent objects of meteor showers. Most notably are the asteroids 2003 EH1 generating the Quadrantids and 3200 Phaethon behind the Geminids.

One of three things is going on here, or a combination of them. Perhaps the asteroid was once a comet and at that time expelled material that causes the meteor shower. The comet then became exhausted and all we have left is a small rocky nucleus.

Another possibility is that the asteroid was once part of a comet that at one time expelled material to cause the meteor shower, then the asteroid broke off and the comet was perturbed into a different orbit.

Or maybe the asteroid is still emitting material. A recent example of this is the asteroid Bennu, seen here ejecting material from its surface.

Bottom line: The famous Halley’s Comet spawns the Eta Aquariids in early May and the Orionids in October. It’ll return to the inner solar system in 2061. Other comets, and even some asteroids, produce meteor showers.

Read more about Halley’s Comet and find more about the pronunciation of the name