The Orionid meteor shower will peak around mid-week, with the best morning likely being Wednesday, October 21. Try watching on the mornings of October 20 and 22, too. In 2020, the moon is a waxing crescent at the shower’s peak. It’ll set in the evening hours, before the constellation Orion – the radiant of the Orionid shower – rises in the east in late evening. The Orionids start producing meteors in late evening, but the number of meteors increases after midnight. Typically, the greatest number of Orionid meteors streak the sky during the few hours before dawn. In a moonless sky, you might see as many as 10 to 15 meteors per hour at the Orionids’ peak.

These meteors – vaporizing bits of comet debris from Halley’s Comet – look like streaks of light in the night sky. Many people call them shooting stars.

The 2021 lunar calendars are here! Order yours before they’re gone. Makes a great gift!

Remember, you don’t need any special equipment to enjoy the show. Find an open sky away from pesky artificial lights, enjoy the comfort of a reclining lawn chair and look upward. Find dark locations at EarthSky’s stargazing page.

Just be sure to give yourself at least 20 minutes for your eyes to adapt to the darkness. And you’ll want at least an hour of viewing time. That’s because meteors often come in spurts, followed by lulls.

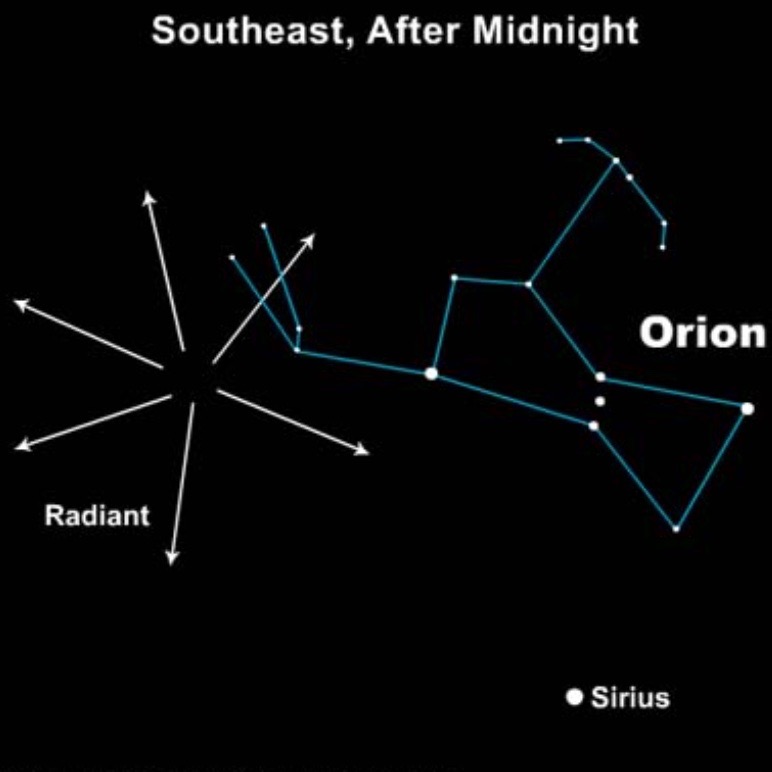

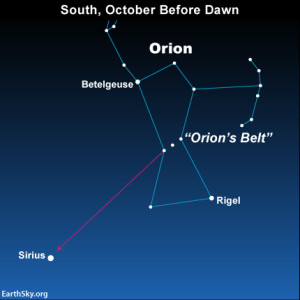

Where is the radiant point for the Orionid meteor shower? The radiant point for the Orionids is in the northern part of Orion, near Orion’s Club. Many see the Hunter as a large rectangle. You’ll surely notice its distinctive row of three medium-bright stars in the middle: those stars represent Orion’s Belt. The brightest star in the sky, Sirius, is to the southeast of Orion on the sky’s dome, and the Belt stars always point to Sirius. This constellation is up in the southeast in the hours after midnight and it’s high in the south before dawn. We will have much more to say about Orion in the months to come, because it’s one of winter’s most prominent constellations.

Do you need to know Orion to see the meteors? Nah. The meteors appear in all parts of the sky. But if you trace the paths of the meteors backward, you’ll see they all seem to come from this constellation.

How many meteors can you expect to see? The number of meteors you’ll see in any meteor shower always varies greatly depending on when and where you watch. Meteor showers are not entirely predictable. That’s the fun of them! In a dark sky, you might see about 15 meteors per hour, or one meteor every few minutes, during the Orionid peak.

When should you watch for Orionid meteors? Meteor showers aren’t just one-night events. The Orionid shower lasts from early October to early November, as Earth passes through a stream of debris left behind by a comet, in this case, the famous Comet Halley. According to the International Meteor Organization (IMO), the Orionids often exhibit several lesser maxima, so meteor activity may remain more or less constant for several nights in a row, centered on a peak night.

So, before dawn on October 20 or 22, the Orionids might match – or nearly match – the numbers before dawn on October 21. The Orionid meteors generally start at late night, or around midnight, and display maximum numbers in the predawn hours. That’s true no matter where you live on Earth, or what time zone you’re in. If you peer in a dark sky between midnight and dawn on October 20, 21 or 22, you’ll likely see some meteors flying.

Want to know when morning dawn (astronomical twilight) first begins? Visit Sunrise Sunset Calendars and remember to check the astronomical twilight box.

What should you watch for during the Orionid shower? If you’d like to make a new friend, or revisit an old one, enjoy the company of the constellation Orion – the radiant of the Orionid meteor shower – on this dark night. Orion rises in the east at late evening, fairly close to midnight. Surrounding Orion are the bright stars typically associated with winter evenings in the Northern Hemisphere. There are many bright stars in this part of the sky, and they are beautiful and colorful. Want to try to identify some? Your best bet is a planisphere.

An hour or two before dawn’s first light, watch for the planet Venus to rise into your eastern predawn sky. Click here for a recommended sky almanac; an almanac can help you determine rising time for Venus in your sky.

The predawn and dawn sky also offers a great view of Sirius, the sky’s brightest star. Watch for it in the south (or overhead if you’re in the Southern Hemisphere) before dawn.

Remember … even one meteor can be a thrill. Just be sure you have a dark sky.

Bring along a blanket or lawn chair – after midnight or before dawn – and lie back comfortably while gazing upward. Although a somewhat modest shower, these swift-moving meteors are sometimes bright, occasionally leaving a persistent train – a glowing streak that lingers momentarily after the meteor has gone!

Where do Orionid meteors originate?

The Orionids stem from debris from the most famous of all comets, Comet Halley, pictured above. The picture shows Comet Halley itself at its 1910 visit. The comet last visited Earth in 1986 and will return next in 2061.

As Comet Halley moves through space, it leaves debris in its wake that strikes Earth’s atmosphere most fully around October 20-22, every year. The comet is nowhere near, but, around this time every year, Earth is intersecting the comet’s orbit.

If the meteors originate from Comet Halley, why are they called the Orionids? The answer is that meteors in annual showers are named for the point in our sky from which they appear to radiate. The radiant point for the Orionids is in the direction of the constellation Orion the Hunter. Hence the name.

Want more about 2020’s Orionid meteor shower? Click here

Bottom line: The waxing crescent moon sets in the evening, providing dark skies for the 2020 Orionid meteor shower. Watch in the dark hours before dawn. Try watching on the mornings of October 20, 21 and 22. A dark sky is always best. Have fun!