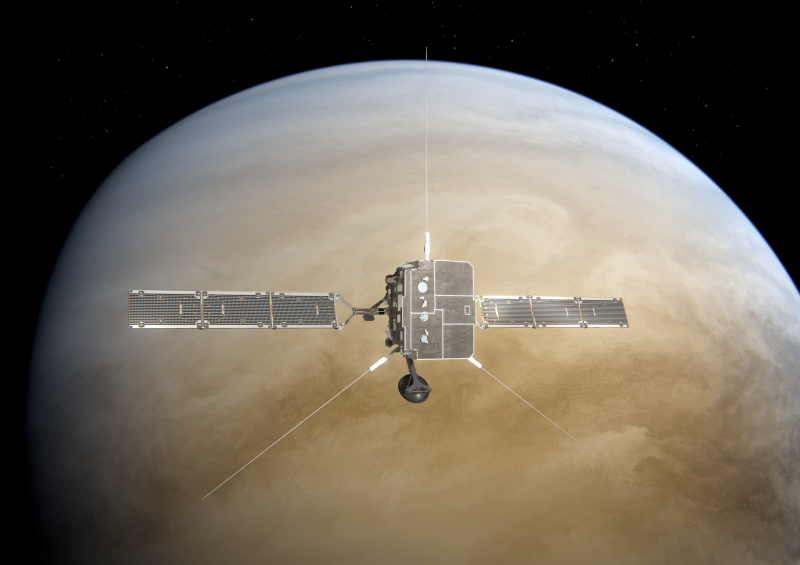

CME strikes Solar Orbiter

Venus is on the far side of the sun from Earth now, about to pass out of our view. And the sun is in an upswing of its 11-year cycle. So it’s blasting out CMEs, aka coronal mass ejections, pretty frequently now, in all directions. Solar Orbiter launched from Earth in February of 2020. And it’s now in an elliptical orbit around the sun. It’s using gravity assists from Venus and Earth to get closer to the sun and to lift itself, gradually, out of the ecliptic plane. Around the middle of this decade, it’ll be high enough above the ecliptic plane to fly over the sun’s poles … something that’s never been done before.

Solar Orbiter had a Venus flyby in the early hours of Sunday, September 4, 2022. But on August 30, a mighty blast from the sun – a coronal mass ejection, or CME – left the sun, headed toward Venus. So this blast headed straight for Solar Orbiter, too. And it struck the spacecraft just two days before the craft’s closest approach to Venus.

The good news is that according to a report from the European Space Agency (ESA), a partner in the Solar Orbiter mission, the spacecraft was unharmed:

Fortunately, there were no negative effects on the spacecraft as the ESA-NASA solar observatory can withstand and in fact measure violent outbursts from our star …

EarthSky’s sun team talked about the August 30 CME in this post

And you can read the sun news from EarthSky every day

Yesterday, @ESASolarOrbiter flew by #Venus for a #GravityAssist that brings it 4.5 mil km closer to the Sun.

As the?? cosied up to the planet, the Sun flung an enormous coronal mass ejection straight at the pair??https://t.co/vuk7RLNItG#SpaceSafety? pic.twitter.com/4ts630F9b4

— ESA Operations (@esaoperations) September 5, 2022

Phew!

CMEs can be dangerous to spacecraft. They are powerful eruptions near the surface of the sun, driven by kinks in the solar magnetic field. If Earth happens to be in the path of a CME, the charged particles can slam into our atmosphere and create beautiful auroral displays. They can’t harm our human bodies here on Earth’s surface, because we’re protected by our planet’s blanket of atmosphere. But CMEs can disrupt satellites in Earth-orbit and even cause them to fail.

But Solar Orbiter is A-okay, ESA said. Because the spacecraft design not only withstands, but also measures, violent outbursts from the sun. In fact, understanding CMEs and tracking their progress through the solar system is part of Solar Orbiter’s mission. ESA said:

Data beamed home since Solar Orbiter encountered the solar storm shows how its local environment changed as the large CME swept by.

While some instruments had to be turned off during its close approach to Venus, to protect them from stray sunlight reflected off of the planet’s surface, Solar Orbiter’s ‘in situ’ instruments remained on, recording among other things an increase in solar energetic particles.

All in all, ESA sounded happy about the CME strike, especially after learning that Solar Orbiter weathered it so well.

Solar Orbiter’s Venus flybys

Sunday’s flyby of Venus took the spacecraft to within roughly 6,000 km (3,700 miles) of the planet. This particular gravity-assist will bring the spacecraft about 4.5 million km (2.8 million miles) closer to the sun than before, at its next perihelion (closest point to the sun).

Solar Orbiter’s orbit is in a resonance orbit with Venus. That means the spacecraft returns near Venus every few orbits, to use the planet’s gravity to alter the spacecraft’s path, or tilt its orbit out of the ecliptic plane.

Sunday’s close approach to Venus – the spacecraft’s third flyby – took place on Sunday at 01:26 UTC, when Solar Orbiter passed 12,500 km (7,800 miles) from the planet’s center, roughly 6,000 km (3,700 miles) from its gassy surface. Jose-Luis Pellon-Bailon, Solar Orbiter Operations Manager, said the flyby went according to plan:

By trading ‘orbital energy’ with Venus, Solar Orbiter has used the planet’s gravity to change its orbit without the need for masses of expensive fuel.

Bottom line: On September 4, 2022, two days before a close flyby of Venus, a CME or blast from the sun struck the sun-observing satellite Solar Orbiter.