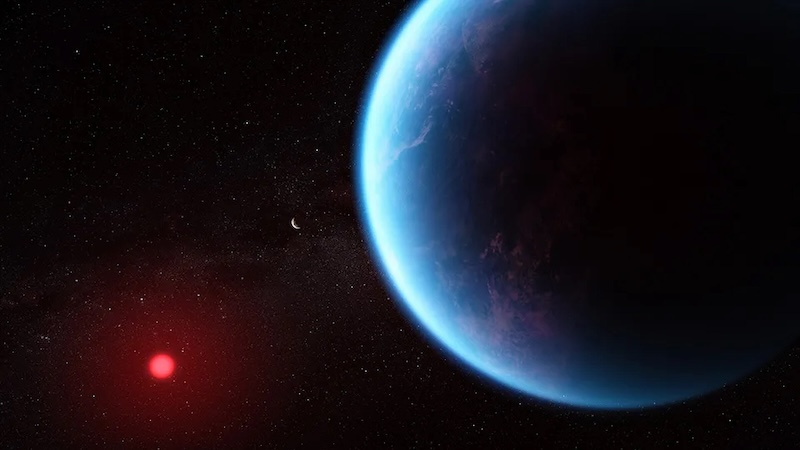

Scientists say that water worlds – planets with deep, global oceans – might be fairly common in our Milky Way galaxy. These worlds would have even more water than Earth. Could anything live there? And could we detect it if it did? On January 3, 2024, an international team of researchers said in a new paper that updated analysis of exoplanet LHS 1140 b – only 50 light-years from Earth – showed it to be a possible water world. Or it’s a mini-Neptune. Scientists aren’t quite sure.

The researchers published their new peer-reviewed findings in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on January 3, 2024.

Meet LHS 1140 b

The planet orbits a small red dwarf star, LHS 1140, about 50 light-years from Earth in the constellation Cetus. It orbits within the habitable zone of its star, the region where temperatures may allow liquid water to exist. Astronomers first detected it in 2017 using the transit method. This method looks for exoplanets crossing in front of their stars as seen from our vantage point here on Earth.

LHS 1140 b is only 1.7 times the radius of Earth and completes an orbit around its star in just 24.7 days.

Water world?

Due to its size compared to Earth, and based on previous studies, astronomers thought LHS 1140 b was probably a rocky planet, a super-Earth. However, as Pultarova wrote at Space.com:

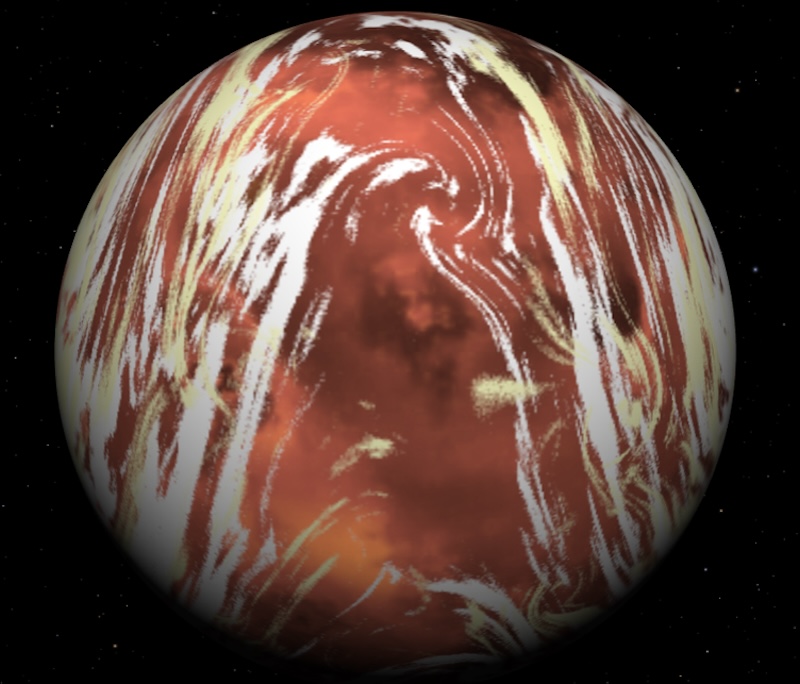

But a new analysis of all available observations has shown that LHS 1140 b is not dense enough to be purely rocky and must either contain much more water than Earth or possess an extensive atmosphere full of light elements such as hydrogen and helium.

This means that the planet, instead of being mostly rocky, could be a water world with more water than Earth. Or it may be a mini-Neptune with an atmosphere of hydrogen and helium. But which is it? Scientists don’t know yet.

The paper stated that if the planet is a water world, then:

A potential outer water layer on this planet is most likely to be in either a frozen or a liquid state, as the planet resides in the water condensation zone. We thus assume the atmospheric layer of LHS 1140 b to be an Earth-like atmosphere with a surface pressure of one bar.

A variant of this model is the Hycean world … a water world surrounded by a thin H/He-rich layer, as was recently proposed for the temperate mini-Neptune K2-18 b.

If it is a water world, then could it be habitable? Tereza Pultarova wrote about the latest findings for Space.com on January 11, 2024. And lead author Charles Cadieux at the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada, told Space.com:

Since the planet is in the habitable zone, it’s really interesting, because if you had water on the surface of a planet inside the habitable zone, you would expect that some of the water is in the liquid state. So that’s a really interesting scenario in terms of habitability.

Or a mini-Neptune?

The other possibility is that LHS 1140 b is a mini-Neptune. It may have a core similar to Earth’s but have a hydrogen-poor atmosphere. Unlike most other mini-Neptunes, it would have only a thin hydrogen and helium atmosphere. As the paper stated:

The planet is either a unique mini-Neptune with a thin ~0.1% hydrogen-helium atmosphere or a water world with a water mass fraction in the 9%-19% range depending on the atmospheric composition and the iron-magnesium ratio of the planetary interior.

Water world with ice shell and geysers?

LHS 1140 b was also one of 17 exoplanets planets featured in a NASA study published last month. The study suggested that these known exoplanets may have oceans covered by an ice shell. This is reminiscent of some moons in our solar system, such as Europa and Enceladus. Further, these worlds could have enough internal heat for geysers to erupt through the ice crust. If so, that sounds a lot like what is happening on Enceladus, with its famous south pole geysers that NASA’s Cassini spacecraft discovered. There is also growing evidence for geysers on Europa, but they seem to be less frequent and on a smaller scale than Enceladus’ geysers.

The estimated thickness of an ice shell on LHS 1140 b is about one mile (1.6 km). The researchers also estimated the geyser activity to be about 639,000 pounds/second (290,000 kg/sec) of water and other material ejected into space. Lead author Lynnae Quick of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said:

Since our models predict that oceans could be found relatively close to the surfaces of Proxima Centauri b and LHS 1140 b, and their rate of geyser activity could exceed Europa’s by hundreds to thousands of times, telescopes are most likely to detect geological activity on these planets.

Webb telescope might give us an answer

Right now, it is difficult to determine which type of planet LHS 1140 b is. We need more detailed analysis. NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope could provide that additional data and determine which scenario is correct. Pulatrova wrote in Space.com:

Cadieux said the researchers have applied to study the LHS 1140 system with JWST to investigate whether the exoplanet has an atmosphere full of hydrogen and helium or whether it appears to have an abundance of water. So far, however, no observations have been planned.

Bottom line: A new study says that an exoplanet 50 light-years away is either a water world or a mini-Neptune. NASA’s Webb telescope might tell us which it is.

Source: Prospects for Cryovolcanic Activity on Cold Ocean Planets

Read more: Did Webb find signs of life on exoplanet K2-18 b?