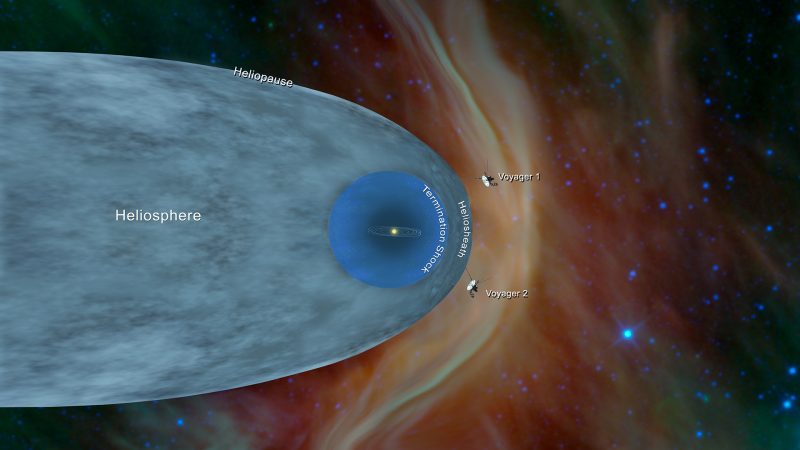

Voyager 1 left Earth in 1977 and crossed the boundary of our sun’s magnetic influence (the heliopause) in 2012. It’s now traveling in the vastness of interstellar space – the space between the stars – and is, at present, the most distant human-made object from us. Interstellar space isn’t quite as empty as a vacuum, and a team of scientists announced on May 10, 2021, that Voyager 1 has now sent back a message, saying it’s detected a faint, monotonous hum of interstellar gas (plasma). Astronomer Stella Koch Ocker of Cornell University led the study and, in a statement, described Voyager 1’s discovery:

It’s very faint and monotone, because it is in a narrow-frequency bandwidth. We’re detecting the faint, persistent hum of interstellar gas.

The study was published May 10, 2021, in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Astronomy.

Although Voyager 1 is traveling in interstellar space, it still feels some influence from the solar wind, a stream of charged particles from our sun. This stream from our sun is no longer the dominant force affecting Voyager 1, however; similar “winds” from other stars mix in. As Voyager 1 reads its environment, it allows scientists to understand how the interstellar medium and solar wind interact and how the the bubble of the solar system’s heliosphere is shaped by external forces.

Voyager 1 has an instrument called a Plasma Wave System, which has been detecting larger eruptions from the sun that affect the plasma, or ionized gas, in interstellar space. It’s when the eruptions are quiet that there’s a background hum. Team member James Cordes of Cornell University described the hum not as an annoying drone, but as something much more pleasant:

The interstellar medium is like a quiet or gentle rain. In the case of a solar outburst, it’s like detecting a lightning burst in a thunderstorm and then it’s back to a gentle rain.

The low-level hum let scientists track how interstellar plasma is distributed in the space through which Voyager 1 is passing. That’s huge! We’ve never had a spacecraft so far from Earth before and so never before could obtain this sort of direct measurement. Team member Shami Chatterjee of Cornell University explained how the hum helps scientists learn more about the interstellar plasma:

We’ve never had a chance to evaluate it. Now we know we don’t need a fortuitous event related to the sun to measure interstellar plasma. Regardless of what the sun is doing, Voyager is sending back detail. The craft is saying, ‘Here’s the density I’m swimming through right now. And here it is now. And here it is now. And here it is now.’ Voyager is quite distant and will be doing this continuously.

Voyager 1 is 14 billion miles (22.5 billion km) from Earth. The signals it sends back to us require nearly an entire earthly day to travel back to Earth. In other words, Voyager 1 is nearly 1 light-day away. For this spacecraft launched in 1977 to still be working outside our solar system and transmitting data is a truly stupendous achievement. Ocker said:

Scientifically, this research is quite a feat. It’s a testament to the amazing Voyager spacecraft. It’s the engineering gift to science that keeps on giving.

Bottom line: Voyager 1 has detected a faint, monotonous hum from plasma (ionized gas) in interstellar space.

Source: Persistent plasma waves in interstellar space detected by Voyager 1