You might easily think of stars as single objects, each one beaming its solitary light from the depths of space. Most stars, though, even those we see as single, reside in multiple star systems. Many systems have two, three or more stars. Some are even known to have as many as six stars. Imagine viewing that from a nearby planet! But recently astronomers announced something unique in their experience. In late January 2021, they said they’d found a six-star system – three pairs of double stars – all producing eclipses as seen from our earthly vantage point.

The system is labeled as TYC 7037-89-1 (or TIC 168789840), and it’s located about 1,900 light-years away in the direction of the constellation Eridanus the River. A new paper about the discovery has been accepted for publication in The Astronomical Journal and a pre-print version is now available on arXiv.

A two-star system is called a binary by astronomers. Binaries consist of two stars orbiting each other, or more specifically, orbiting a common center of gravity. Some of these systems are known to be eclipsing binaries; the two stars eclipse each other, as seen from Earth. This six-star system is what astronomers call a sextuplet. There are other known sextuple star systems, but this is the first one discovered with three eclipsing binaries. In other words, it’s three pairs of double stars whose orbits happen to tip into our line of sight, so that we can observe the stars passing in front of one another.

An international team of scientists – led by data scientist Brian Powell and astrophysicist Veselin Kostov at Goddard – discovered this fascinating system, TYC 7037-89-1. They used data from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS).

The three sets of eclipsing binaries are engaged with each other, in kind of a stellar dance.

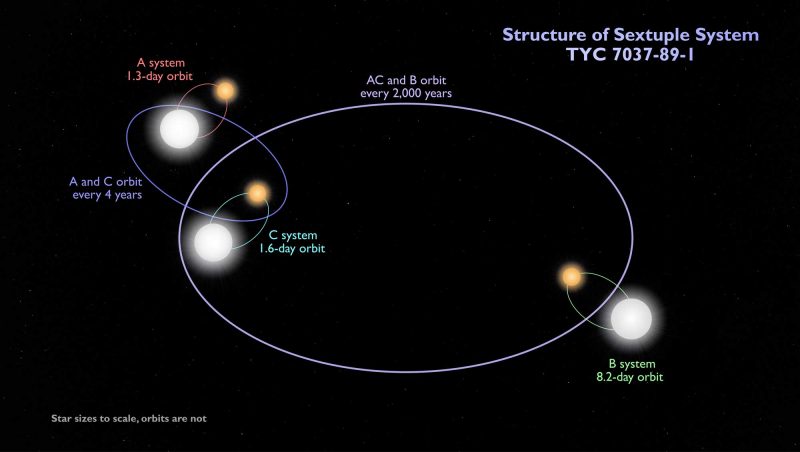

The three sets of binaries in the TYC 7037-89-1 system are referred to as A, B and C. In both the A and C systems, the stars orbit each other about every 1 1/2 days, while in the B system, the stars circle each other every eight days. The A and C systems, in turn, orbit each other every four years. The B system is much farther out though, and orbits both the A and C systems every 2,000 years. With me so far?

The largest, main stars in each binary are slightly larger and more massive than our sun. They are also close to the same temperature as the sun. The secondary stars, however, are only half the size of the sun and half as hot.

So how did the astronomers find this intriguing star system? They were searching for dips in the brightness of stars specifically due to eclipsing binaries. Using the NASA Center for Climate Simulation’s Discover supercomputer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, they monitored the changing brightness of about 80 million stars that had been observed by TESS. Most of the candidates they were looking for would be regular binaries, that is two stars orbiting around their common center of gravity as a pair.

They found 450,000 candidates, and of those, at least 100 had three or more stars. TYC 7037-89-1 was one of them, with an incredible six stars locked together by gravity.

It is fortunate that we can see the eclipses of the stars in this system, since they can provide detailed measurements of the stars’ sizes, masses, temperatures, separation and distance to the system. That data will lead to even better scientific models of star formation and evolution. From the paper:

As a consequence of its rare composition, structure, and orientation, this object can provide important new insight into the formation, dynamics, and evolution of multiple star systems. Future observations could reveal if the intermediate and outer orbital planes are all aligned with the planes of the three inner eclipsing binaries.

There are a lot of questions about TYC 7037-89-1 that scientists wish they could answer. Why is it that the primary and secondary stars in each of the three binaries have such similar properties? How did those three pairs of binaries become gravitationally bound together in the first place?

Astronomers now think that virtually every sunlike star has a stellar companion when it first forms. They think that, a few billion years ago, our own sun had a binary companion, which has been dubbed Nemesis. This erstwhile companion is calculated to have been about 17 times farther from the sun than the orbit of Neptune.

In the sun’s case, however, our former companion star broke free of its gravitational bond. Since no sign of it has been found in the modern-day solar system, astronomers can only suppose Nemesis now moves, as our sun does, in its own grand orbit around the center of our Milky Way, but elsewhere in our galaxy.

Bottom line: An international team of astronomers has discovered a unique sextuplet star system where eclipses of all six stars can be seen from Earth.

Source: TIC 168789840: A Sextuply-Eclipsing Sextuple Star System