The Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra, Australia announced evidence today (April 6, 2016) that a series of massive supernova explosions near our solar system showered Earth with radioactive debris. How near? The scientists believe the supernovae in this case were less than 300 light-years away, close enough to be visible during the day and comparable to the brightness of the moon. What evidence? It comes in the form of radioactive iron-60, which these scientists found in sediment and crust samples taken from Earth’s Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

Anton Wallner, a nuclear physicist at ANU’s Research School of Physics and Engineering, led the research. He said in a statement that the iron-60 was concentrated in a period between 3.2 and 1.7 million years ago, which is relatively recent in astronomical terms. He said:

We were very surprised that there was debris clearly spread across 1.5 million years. It suggests there were a series of supernovae, one after another.

It’s an interesting coincidence that they correspond with when the Earth cooled and moved from the Pliocene into the Pleistocene period.

These scientists say that – although Earth would have been exposed to an increased cosmic ray bombardment – the radiation would have been too weak to cause direct biological damage or trigger mass extinctions.

On the other hand, theories suggest cosmic rays from the supernovae could have increased cloud cover.

It’s known that supernova explosions create many heavy elements and radioactive isotopes and hurl them into space. One of these isotopes is iron-60, which decays with a half-life of 2.6 million years (unlike its stable cousin iron-56, which makes up more than 90% of the iron around us on Earth today).

Because it decays so relatively rapidly, any iron-60 dating from the Earth’s formation more than four billion years ago has long since disappeared.

Finding radioactive iron-60 in sediment and crust samples from Earth’s oceans must mean something. These scientists believe it means that supernovae exploded near Earth.

Anton Wallner said he was intrigued by first hints of iron-60 in samples from the Pacific Ocean floor, found a decade ago by a group at TU Munich.

He assembled an international team to search for interstellar dust. The team came from institutions around the globe, including from Australia, the University of Vienna in Austria, Hebrew University in Israel, Shimizu Corporation and University of Tokyo, Nihon University and University of Tsukuba in Japan, Senckenberg Collections of Natural History Dresden and Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR) in Germany.

They searched 120 ocean-floor samples spanning the past 11 million years.

The first step was to extract all the iron from the ocean cores.

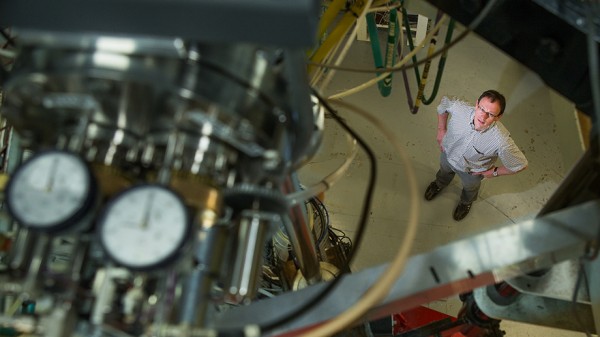

The team then separated the tiny traces of interstellar iron-60 from the other terrestrial isotopes using the Heavy-Ion Accelerator at ANU and found it occurred all over the globe.

The age of the cores was determined from the decay of other radioactive isotopes, beryllium-10 and aluminium-26, using accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) facilities at Dresden AMS (DREAMS) of HZDR, Micro Analysis Laboratory (MALT) at the University of Tokyo and the Vienna Environmental Research Accelerator (VERA) at the University of Vienna.

The dating showed the fallout had only occurred in two time periods, 3.2 to 1.7 million years ago and eight million years ago. The scientists’ statement concludes:

A possible source of the supernovae is an aging star cluster, which has since moved away from Earth…

The cluster has no large stars left, suggesting they have already exploded as supernovae, throwing out waves of debris.

Bottom line: A series of massive supernova explosions near our solar system showered Earth with radioactive debris, according to a comprehensive study of radioactive iron-60, found in sediment and crust samples from Earth’s oceans.