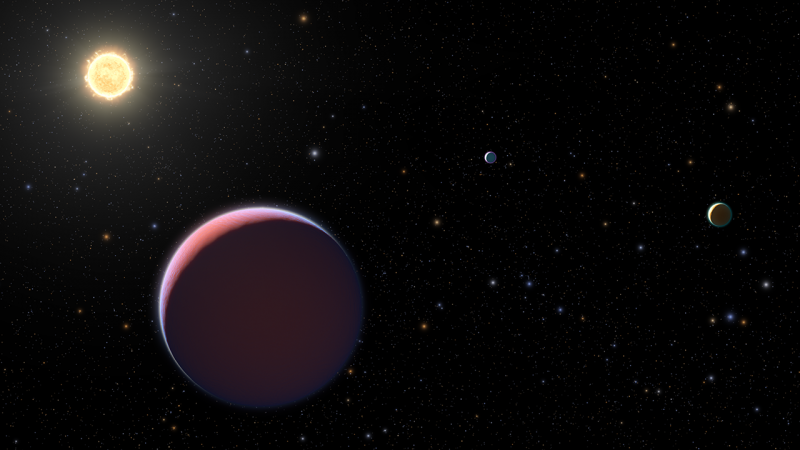

Among the strangest exoplanets discovered so far are the so-called super-puff or cotton candy planets. They appear to have extremely low densities, lower even than our solar system’s planet Saturn, which has long been said to be so “light” it could float on water, if you could find an ocean big enough to hold it. Researchers at Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C., have developed a new line of thought about these exotic worlds. They announced on March 2, 2020, that some super-puff planets aren’t as puffy as first thought. What if there’s another explanation? Lead researcher Anthony Piro at Carnegie explained in a statement:

We started thinking, what if these planets aren’t airy like cotton candy at all? What if the super-puffs seem so large because they are actually surrounded by rings?

The associated peer-reviewed paper was published in The Astronomical Journal on February 28.

Super-puff or cotton candy planets are characterized by their large radii in contrast to their not-so-large masses. Their densities are very low. Their apparent differences from any planets in our solar system made them a surprising discovery when they were first began to be found, a few years ago.

It’s an interesting idea, that the super-puffs – at least some of them – might be more like Saturn and the other giant planets in our solar system than first thought. All four of the gas giant planets in our solar system – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune – are known to have rings. Could many of the super-puffs have rings instead of super low densities?

Exoplanets are difficult to detect; it’s hard to see them in the glare of distant stars. Rings around exoplanets would be even more difficult. The researchers wondered if alien astronomers on distant exoplanets could look back at our solar system and see Saturn’s rings. Or, from a great distance away, would they mistake Saturn for a super-puff? According to Shreyas Vissapragada at Caltech:

We started to wonder, if you were to look back at us from a distant world, would you recognize Saturn as a ringed planet, or would it appear to be a puffy planet to an alien astronomer?

In thinking through this question, the researchers took into consideration how a large ringed planet would appear as it transited in front of its star, and the kind of ring material that might exist around super-puffs. Their conclusion is that rings might explain some of the super-puffs discovered, but probably not all of them. According to Piro:

These planets tend to orbit in close proximity to their host stars, meaning that the rings would have to be rocky, rather than icy. But rocky ring radii can only be so big, unless the rock is very porous, so not every super-puff would fit these constraints.

The researchers found three good candidate super-puffs for having rings: Kepler-87c, Kepler-177c and HIP 41378f.

Three of these planets were studied recently by the Hubble Space Telescope, orbiting the sunlike star Kepler-51, about 2,600 light-years away. They are almost the size of Jupiter, but only 1/100th as massive. They have atmospheres composed of the lightweight gases hydrogen and helium, covered by a thick layer of methane haze.

Those planets also appear to be rapidly shrinking, losing billions of tons of material into space every second, suggesting that the cotton candy characteristics may just be a transitory phase in their evolution. They may end up looking more like mini-Neptunes.

Determining whether any of these planets actually do have rings will require follow-up observations by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled to launch in 2021. If they do, that would help scientists learn more about how such worlds form and how they compare to actual super-puffs and other giant exoplanets, as well as the giant planets in our own solar system.

Bottom line: A new study suggests that some cotton candy exoplanets may not be as puffy as first thought, but instead have rings, like Saturn.

Source: Exploring Whether Super-puffs can be Explained as Ringed Exoplanets