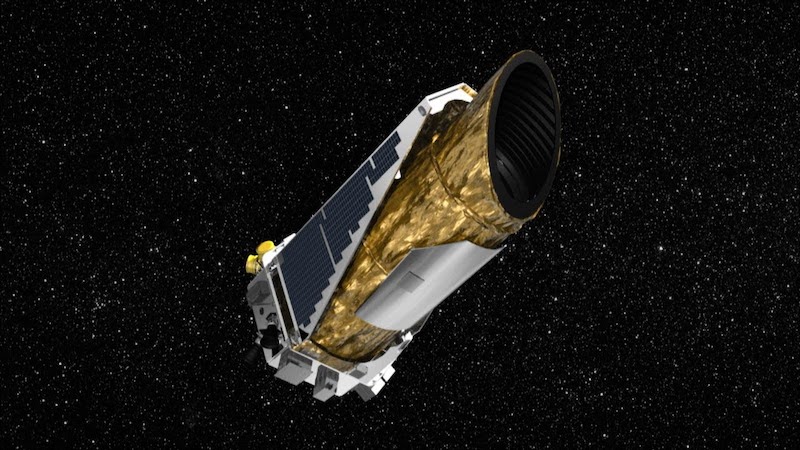

The number of known exoplanets made a big jump up in November 2021, when astronomers announced a whopping 301 newly confirmed planets and an additional 366 new planet candidates. NASA’s Kepler planet-hunter – a space observatory – gathered the data. Kepler launched and began operations in 2009. It ran out of fuel and was retired in late 2018. But astronomers are still mining the mission’s data, making new discoveries of distant worlds.

NASA scientists submitted the first of two peer-reviewed papers to the Astrophysical Journal on November 17, 2021. It is available as a preprint on arXiv. A team of scientists from UCLA submitted the second peer-reviewed paper, which The Astronomical Journal published on November 23, 2021. It is also available as a preprint on arXiv.

EarthSky 2022 lunar calendars now available! They make great gifts. Order now. Going fast!

Kepler data yields hundreds of new exoplanets

Overall, the Kepler mission was immensely successful. As of December 6, 2021, astronomers recognize 4,888 confirmed exoplanets. It’s not an exaggeration to say that Kepler single-handedly discovered most of the exoplanets we know about today.

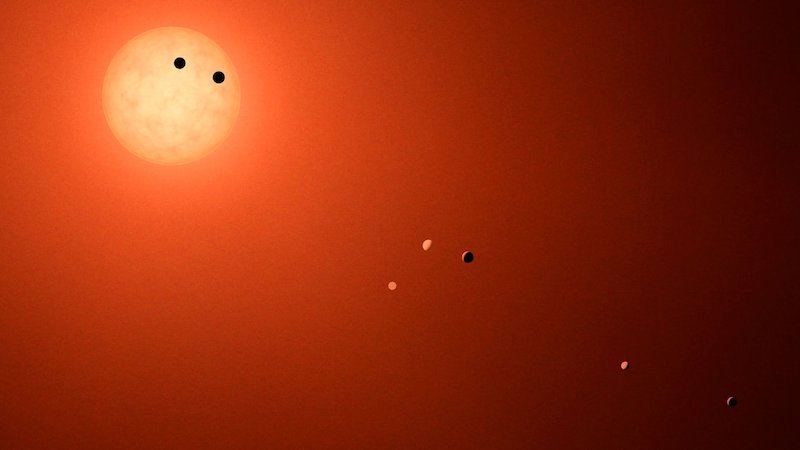

Those exoworlds – orbiting distant stars – range from Earth-sized and super-Earth-sized to ones larger than Jupiter. Some orbit their stars much closer than Mercury does our sun, and others are sub-Neptunes, midway in size between Earth and Neptune. No such planets exist in our own solar system.

The NASA research team used a machine learning process called ExoMiner to find 301 new validated planets. Meanwhile, astronomers at UCLA found 366 new planetary candidates using their own new algorithm.

ExoMiner uncovers new exoplanets

First, ExoMiner. ExoMiner is a deep neural network that leverages NASA’s supercomputer called Pleiades. Scientists designed it to better distinguish between real planets and false positives. That is to say, it uses previous positive and false detections to learn how to better tell the difference between the two.

ExoMiner doesn’t work alone, however. It supplements the human scientists who also go through the data. That task can be very time-consuming, and that’s where ExoMiner comes in. Jon Jenkins, an exoplanet scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center, stated:

Unlike other exoplanet-detecting machine learning programs, ExoMiner isn’t a black box. There is no mystery as to why it decides something is a planet or not. We can easily explain which features in the data lead ExoMiner to reject or confirm a planet.

ExoMiner found the new exoplanets by analyzing the data from the remaining Kepler dataset of possible planets in the Kepler Data Archive. Before this, scientists had already known of them from the Kepler Science Operations Center pipeline, but they were still just candidates. Now, ExoMiner has confirmed them as actual planets.

Hamed Valizadegan, ExoMiner project lead and machine learning manager with the Universities Space Research Association at Ames, said:

When ExoMiner says something is a planet, you can be sure it’s a planet. ExoMiner is highly accurate and in some ways more reliable than both existing machine classifiers and the human experts it’s meant to emulate because of the biases that come with human labeling.

Jenkins added:

These 301 discoveries help us better understand planets and solar systems beyond our own, and what makes ours so unique.

Transiting exoplanet candidates in K2 data

But wait, there’s more! The next day, astronomers at UCLA announced their own finding of 366 new exoplanet candidates in the Kepler data. In contrast to the NASA team, they used their own new algorithm designed in-house. Co-author Erik Petigura at UCLA said:

Discovering hundreds of new exoplanets is a significant accomplishment by itself, but what sets this work apart is how it will illuminate features of the exoplanet population as a whole.

Petigura and lead author Jon Zink are part of an international team of astronomers called the Scaling K2 project. The project uses data from the K2 phase of the Kepler mission. K2 was an extended mission phase designed to compensate for a mechanical malfunction on the telescope during the primary mission. The original mission ended in 2013. Petigura said:

The catalog and planet detection algorithm that Jon and the Scaling K2 team devised is a major breakthrough in understanding the population of planets. I have no doubt they will sharpen our understanding of the physical processes by which planets form and evolve.

Ultimately, the entire data set from K2 was analyzed, which consisted of 500 terabytes and more than 800 million images of stars. The researchers used UCLA’s Hoffman2 Cluster to process the data.

How many planets are there?

As well as the new exoplanets, the research team also identified 381 planets that were already known about. Altogether, the team found 747 unique planet candidates and 57 multiplanet systems in the K2 data.

Scientists want to learn which stars are most likely to have planets and how many star systems have the necessary building blocks for planets. As Zink noted:

We need to look at a wide range of stars, not just ones like our sun, to understand that. The discovery of each new world provides a unique glimpse into the physics that play a role in planet formation.

The Kepler spacecraft ran out of fuel in 2018, and NASA announced the end of the mission on October 30, 2018. Now, NASA’s TESS mission is following in Kepler’s footsteps and finding many more planets of its own. According to Valizadegan:

Now that we’ve trained ExoMiner using Kepler data, with a little fine-tuning, we can transfer that learning to other missions, including TESS, which we’re currently working on. There’s room to grow.

Many more worlds waiting to be found

These new discoveries are exciting, and there are many more worlds waiting to be found. In fact, scientists estimate that there are billions of planets in our galaxy alone. And those are the ones orbiting stars. In addition, there may be millions or more planets that don’t even orbit any stars. These are nomad planets, drifting in space alone. Scientists are discovering more of those now as well. It boggles the mind to think of how many worlds are out there, especially when you remember that there are also billions of galaxies!

Bottom line: Scientists have found hundreds of new exoplanets in data from the Kepler mission. These include 301 newly confirmed exoplanets and 366 new planetary candidates.

Source: Scaling K2. IV. A Uniform Planet Sample for Campaigns 1–8 and 10–18

Source (preprint): Scaling K2. IV. A Uniform Planet Sample for Campaigns 1-8 and 10-18