More evidence for active Venus volcanoes

Scientists have found two more pieces of direct geological evidence of recent volcanic activity on the planet next-inward from Earth, Venus. This is the 2nd time such evidence has been found in data from the Magellan spacecraft, which mapped 98% of Venus’ surface from 1990 to 1992. The images it generated remain our most detailed of Venus to date. Scientists in Italy analyzed archival data from Magellan. They found surface changes indicating the formation of new rock from lava flows linked to volcanoes that were in eruption while the spacecraft orbited the planet. Davide Sulcanese of d’Annunzio University in Pescara, Italy, who led the study, said:

By analyzing the lava flows we observed in two locations on the planet, we have discovered that the volcanic activity on Venus could be comparable to that on Earth.

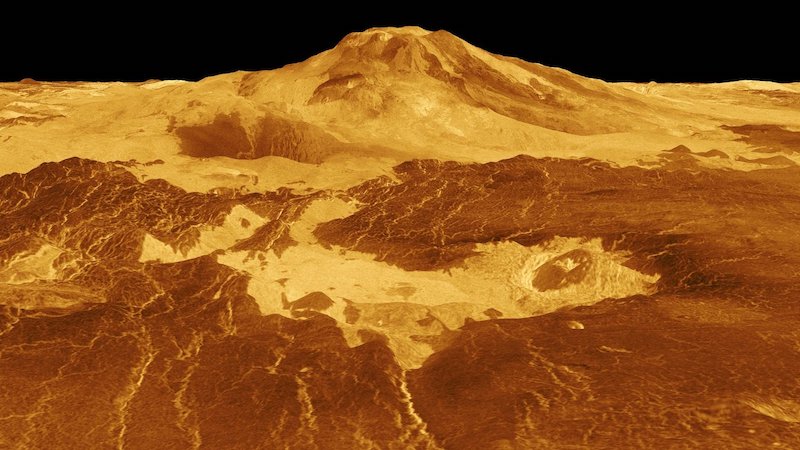

This latest discovery builds on the historic 2023 discovery of images from Magellan’s synthetic aperture radar that revealed changes to a vent associated with the volcano Maat Mons near Venus’ equator.

The 2023 radar images proved to be the first direct evidence of a recent volcanic eruption on the planet. By comparing Magellan radar images over time, the authors of that earlier study spotted changes caused by the outflow of molten rock from Venus’ subsurface filling the vent’s crater and spilling down the vent’s slopes.

The scientists published the 2024 study in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Astronomy.

Radar backscatter

For the new study, the researchers likewise focused on archival data from Magellan’s synthetic aperture radar. Radio waves sent by the radar traveled through Venus’ thick cloud cover, then bounced off the planet’s surface and back to the spacecraft. Called backscatter, these reflected radar signals carried information about the rocky surface material they encountered.

The two locations studied were the volcano Sif Mons in Eistla Regio and the western part of Niobe Planitia, which is home to numerous volcanic features. By analyzing the backscatter data received from both locations in 1990 and again in 1992, the researchers found that radar signal strength increased along certain paths during the later orbits. These changes suggested the formation of new rock, most likely solidified lava from volcanic activity that occurred during that two-year period. But they also considered other possibilities, such as the presence of micro-dunes (formed from windblown sand) and atmospheric effects that could interfere with the radar signal.

To help confirm new rock, the researchers analyzed Magellan’s altimetry (surface height) data to determine the slope of the topography and locate obstacles that lava would flow around. Study co-author Marco Mastrogiuseppe of Sapienza University of Rome said:

We interpret these signals as flows along slopes or volcanic plains that can deviate around obstacles such as shield volcanoes like a fluid. After ruling out other possibilities, we confirmed our best interpretation is that these are new lava flows.

Using flows on Earth as a comparison, the researchers estimate new rock that was emplaced in both locations to be between 10 and 66 feet (3 and 20 meters) deep, on average. They also estimate that the Sif Mons eruption produced about 12 square miles (30 square kilometers) of rock, enough to fill at least 36,000 Olympic-size swimming pools. The Niobe Planitia eruption produced about 17 square miles (44 square km) of rock, which would fill 54,000 Olympic swimming pools. As a comparison, the 2022 eruption of Mauna Loa in Hawaii, Earth’s largest active volcano, produced a lava flow with enough material to fill 100,000 Olympic pools.

Scott Hensley, senior research scientist at JPL and co-author of the 2023 study, said:

This exciting work provides another example of volcanic change on Venus from new lava flows that augments the vent change Dr. Robert Herrick and I reported last year. This result, in tandem with the earlier discovery of present-day geologic activity, increases the excitement in the planetary science community for future missions to Venus.

Scientists study active volcanoes to understand how a planet’s interior can shape its crust, drive its evolution, and affect its habitability. The discovery of recent volcanism on Venus provides a valuable insight to the planet’s history and why it took a different evolutionary path than Earth.

Figuring out volcanoes

Hensley is the project scientist for NASA’s upcoming VERITAS mission, and Mastrogiuseppe is a member of its science team.

Short for Venus Emissivity, Radio science, InSAR, Topography, And Spectroscopy, VERITAS is slated to launch early next decade. It will use a state-of-the-art synthetic aperture radar to create 3D global maps and a near-infrared spectrometer to figure out what Venus’ surface is made of. It’ll also be tracking volcanic activity. In addition, the spacecraft will measure the planet’s gravitational field to determine its internal structure. Suzanne Smrekar, a senior scientist at JPL and principal investigator for VERITAS, said:

These new discoveries of recent volcanic activity on Venus by our international colleagues provide compelling evidence of the kinds of regions we should target with VERITAS when it arrives at Venus. Our spacecraft will have a suite of approaches for identifying surface changes that are far more comprehensive and higher resolution than Magellan images. Evidence for activity, even in the lower-resolution Magellan data, supercharges the potential to revolutionize our understanding of this enigmatic world.

Bottom line: An analysis of radar data from the Magellan spacecraft has revealed more evidence for active Venus volcanoes. It appears two volcanoes erupted in the early 1990s. This adds to the 2023 discovery of a different active volcano in Magellan data.

Read more: Active volcanoes on Venus found in Magellan data

Source: Evidence of ongoing volcanic activity on Venus revealed by Magellan radar