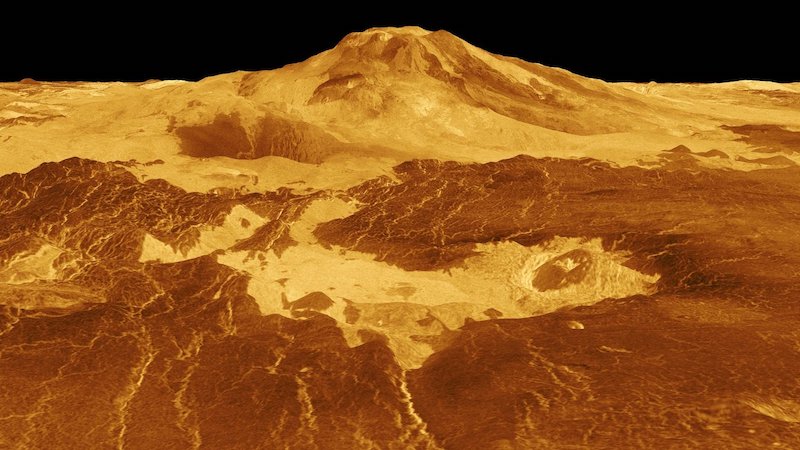

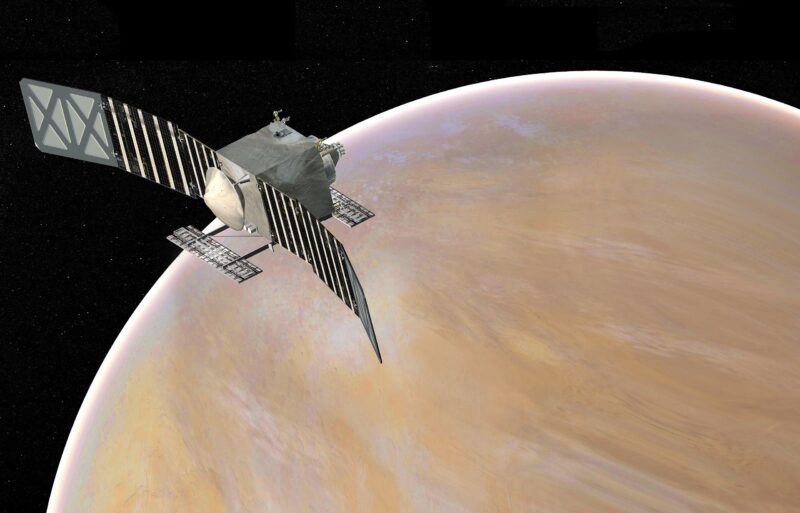

The surface of Venus is lead-meltingly hot, and its atmosphere is crushing (with pressures some 100 times greater than that on Earth) and poisonous. Although 10 Soviet Venera probes have achieved soft landings there, the longest time a Venus lander has communicated back to Earth was only 110 minutes (Venera 12 in 1978). So Venus is tough! Yet launch windows to our sister world – which orbits our sun just one step inward from Earth – open every 19 months. And scientists want to study Venus from orbit. They want to learn what lies hidden under its blanket of clouds. The next NASA mission to Venus will be VERITAS – a Venus orbiter – due to launch within the coming decade.

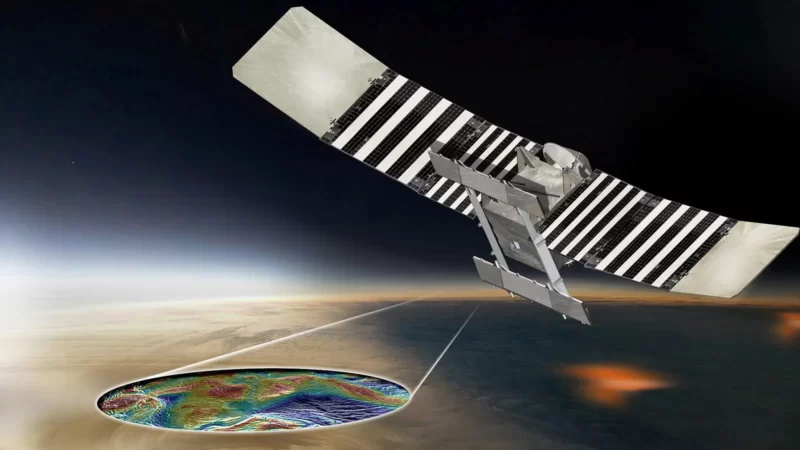

It’ll examine Venus’ surface from above the planet’s sulfuric acid clouds. It might even be able to find out more about Venus’ interior. But how can scientists prepare to study a planet as hostile and as largely unknown as Venus?

One way – in August 2023 – involved a trip to Iceland. The VERITAS principal investigator, Suzanne Smrekar of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in a statement on September 19, 2023:

Iceland is a volcanic country that sits atop a hot plume. Venus is a volcanic planet with plentiful geological evidence for active plumes. Its geological similarities make Iceland an excellent place to study Venus on Earth, helping the science team prepare for Venus.

Iceland as an analog for future VERITAS mission to Venus

VERITAS means truth in Latin. The name VERITAS for this mission to Venus also stands for Venus Emissivity, Radio science, InSAR, Topography, And Spectroscopy.

And we know that Venus – whose size and density make it a kind of “twin” to Earth – is a world of volcanoes. Radar studies of Venus, from Earth and from orbit, have revealed tens of thousands of known volcanoes, big and small, on the planet’s surface.

But are Venus’ volcanoes active? In recent years, there’s been growing evidence that at least some Venus volcanoes indeed are still active. And that possibility makes Venus an exciting target for exploration!

So, to prepare, scientists wanted to study another place known for its volcanic activity. Iceland is one of the closest Earth analogs to Venus, said VERITAS scientists, with its active volcanoes and rough terrain similar to what we’ve glimpsed on our sister world.

Overall, the research team spent two weeks in Iceland for their field campaign. The team included 19 scientists from the U.S., Germany, Italy and Iceland.

VERITAS mission scientists in Iceland

Studying Iceland’s volcanic deposits

Iceland has many volcanic features, which can be used as terrestrial analogs for volcanism on Venus. The research team studied the Askja volcanic deposits and the Holuhraun lava field in the Icelandic Highlands for the first half of the field campaign. This region contains recent lava flows.

For the second half of the field campaign, the researchers focused on the Fagradalsfjall region on the Reykjanes Peninsula of southwestern Iceland. Both regions are volcanically active and their rocky landscapes resemble those of Venus. How do we know? The truth is, we’ve seen only a very few closeup views of Venus’ surface so far, from the Soviet Venera landers in 1975 and 1982.

But those images are enough, along with radar images from orbiting spacecraft, to provide some idea of what Venus’ surface is like.

Radar data from the sky

Studying the volcanic features on the ground in Iceland was only part of the field campaign. In addition, the German Aerospace Center (DLR) gathered radar data from aircraft flying overhead. Daniel Nunes, VERITAS deputy project scientist at JPL and Iceland campaign planning lead, said:

The JPL-led science team was working on the ground while our DLR partners flew overhead to gather aerial radar images of the locations we were studying. The radar brightness of the surface relates to the properties of that surface, including texture, roughness and water content. We collected information in the field to ground-truth the radar data that we will use to inform the science that VERITAS will do at Venus.

The researchers used synthetic aperture radar onboard a Dornier 228-212 aircraft flying about 20,000 feet (6,000 meters) in altitude. The radar collected data in both S-band (wavelength of about 12 centimeters, or 4.7 inches) and X-band (wavelength about 3 centimeters, or 1.2 inches). NASA’s previous Magellan mission to Venus in the 1990s used S-band. VERITAS, however, will use the shorter X-band wavelength.

Both bands are useful for the studies in Iceland. The researchers can use them to refine the computer algorithms that VERITAS will use. This way, VERITAS will be able to spot any changes on the surface that may have occurred since the Magellan mission. This is especially important for detecting changes related to volcanic activity.

A library of surface volcanic textures

Another primary goal of the field campaign was to create a sample library. This would contain samples of various volcanic surface textures in Iceland. Later, by comparing them to future data from VERITAS, scientists will be able to better understand what kinds of volcanic processes occurred or are occurring on Venus. Smrekar said:

The different surface characteristics and features seen on Venus relate to volcanic processes, which relate back to the interior of Venus. This data is going to be valuable to VERITAS to help us better understand Venus. It will also help the European Space Agency’s EnVision mission, which will study Venus’ surface with S-band radar, and the community at large that wants to understand radar observations of volcanic planetary surfaces.

In addition, scientists with DLR also collected compositional information for the lava flows with a camera that emulates the Venus Emissivity Mapper (VEM) instrument. These data will support the spectral library being created at the Planetary Spectroscopy Laboratory in Berlin, Germany.

A team effort

The current studies in Iceland provide valuable scientific training for the upcoming VERITAS mission. And indeed, the field campaign was a team effort, as Nunes noted:

It was a great dynamic. We pushed hard and helped each other out. From borrowing gear to driving to the study sites and buying supplies, everyone hustled to make it happen.

The VERITAS mission

NASA first proposed the VERITAS mission back in 2020 as part of the Discovery Program. VERITAS will peer through the dense clouds of Venus with radar and a near-infrared spectrometer to create 3-D global maps of the planet and analyze what the surface is composed of (we do know already that most of the surface is volcanic basalt). By measuring Venus’ gravitational field, VERITAS could also determine the structure of the planet’s interior. The VERITAS mission will provide the most detailed analysis of Venus ever obtained by an orbiting spacecraft.

It will study Venus’ geology and the similarities it may have to that of the early Earth. The planet’s warm crust is thought to be a good analog to that of Earth a few billion years ago, when tectonic plates were just starting to form. Did the same thing happen on Venus?

There has been growing evidence for current volcanism on Venus. VERITAS will be able to look for hotspots from active eruptions using its spectrometer, and the radar could detect active faulting, which would be evidence for current tectonic activity. The spectrometer could also detect rocks that had been formed from hot magma, before the chemical composition of the rocks had been altered by the corrosive atmosphere. Knowing how geologically active Venus still is, or isn’t, would also help scientists figure out how much water is in the interior of the planet.

Bottom line: An international team of scientists recently studied volcanic activity on Iceland. The data will be used to help prepare for the future VERITAS mission to Venus.