The habitable zone – or Goldilocks zone – around a star is of great interest to astrobiologists, those scientists probing for life beyond Earth. It is the region where temperatures on a rocky world are suitable for liquid water to exist. Astronomers have been discovering many exoplanets orbiting within habitable zones. But they wonder, just what percentage of exoplanets in our Milky Way galaxy might orbit within a habitable zone? In other words, what is the potential for life in our galaxy? Now, a new method devised and announced by scientists at the University of Warwick in the U.K. has found a cooler planet that had been previously “lost” close to its star’s habitable zone. The planet is called NGTS-11b. These scientists say their method promises to help find many more such worlds orbiting in the habitable zones of their stars.

This rediscovery was published in the peer-reviewed journal The Astrophysical Journal Letters on July 20, 2020.

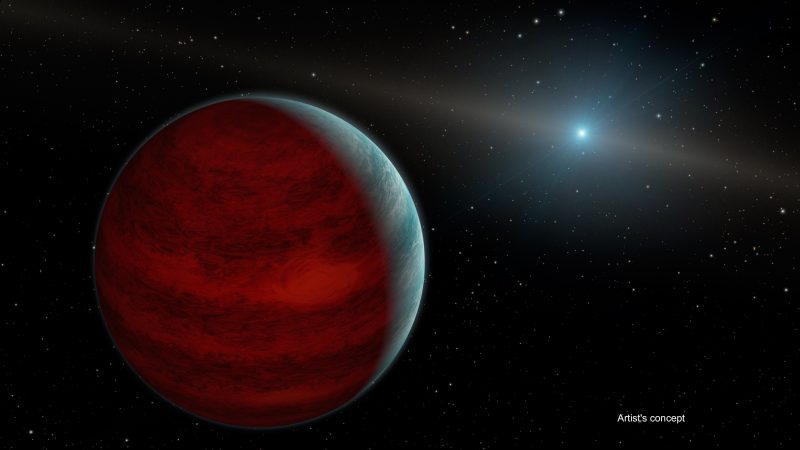

NGTS-11b is about the size and mass of Saturn. It orbits its star every 35 days. It is five times closer to its star than Earth is to the sun and is 620 light-years away.

Astronomers think that that it is just one of hundreds of “lost worlds” that this new technique can help rediscover.

What do scientists mean by lost worlds?

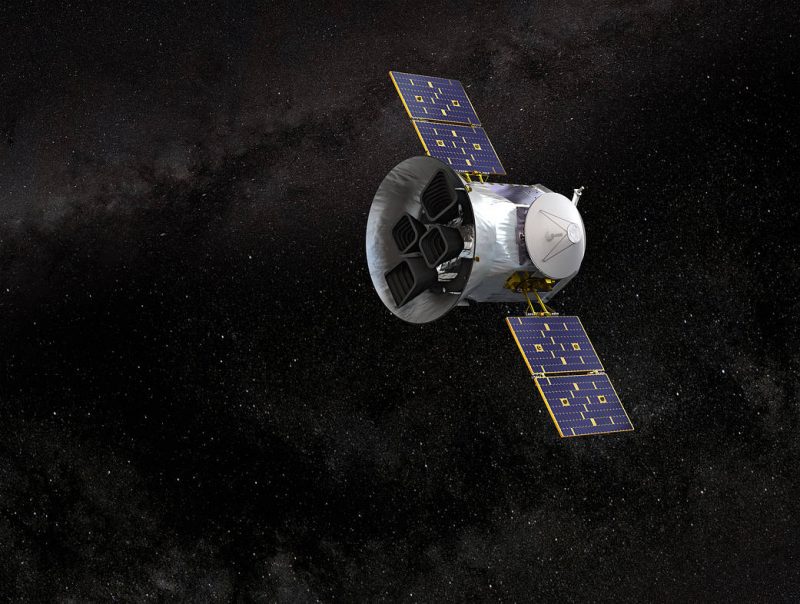

Basically, they are exoplanets discovered by the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) space telescope but detected only once. TESS finds planets by observing them transit in front of their stars, but only scans most sections of the sky for 27 days. Any planets that have orbital periods longer than 27 days would only appear once in the observations. If a second observation cannot be obtained, the planet is considered “lost” as it were. But the researchers at the University of Warwick were able to reobserve some of these stars, using the Next-Generation Transit Survey (NGTS) in Chile, for up to 72 days. That way, planets with longer orbits could be detected. That’s how NGTS-11b was refound, by catching it transiting a second time. Samuel Gill, lead author of the paper, explained:

By chasing that second transit down we’ve found a longer period planet. It’s the first of hopefully many such finds pushing to longer periods.

These discoveries are rare but important, since they allow us to find longer period planets than other astronomers are finding. Longer period planets are cooler, more like the planets in our own solar system.

NGTS-11b has a temperature of only 160 degrees Celsius (320 degrees Fahrenheit), cooler than Mercury and Venus. Although this is still too hot to support life as we know it, it is closer to the Goldilocks zone than many previously discovered planets which typically have temperatures above 1000 degrees Celsius (1800 F).

Co-author Daniel Bayliss said:

This planet is out at a thirty-five-day orbit, which is a much longer period than we usually find them. It is exciting to see the Goldilocks zone within our sights.

Another co-author, Pete Wheatley, added:

The original transit appeared just once in the TESS data, and it was our team’s painstaking detective work that allowed us to find it again a year later with NGTS.

NGTS has twelve state-of-the-art telescopes, which means that we can monitor multiple stars for months on end, searching for lost planets. The dip in light from the transit is only 1% deep and occurs only once every 35 days, putting it out of reach of other telescopes.

The researchers expect that NGTS-11b will be just the first of hundreds of lost worlds found once again. Gill said:

There are hundreds of single transits detected by TESS that we will be monitoring using this method. This will allow us to discover cooler exoplanets of all sizes, including planets more like those in our own solar system. Some of these will be small rocky planets in the Goldilocks zone that are cool enough to host liquid water oceans and potentially extraterrestrial life.

Being able to detect multiple transits of a planet is crucial for determining its orbital period and mass, which cannot always be done by TESS alone. From the paper:

It is important to note that we have been able to determine the mass and radius of this relatively long-period exoplanet with a very modest number of radial-velocity measurements (nine with HARPS and six with FEROS). The detection of the second transit with NGTS was crucial for tightly constraining the possible orbital periods, and this serves to demonstrate the value of intense photometric monitoring in following up single-transit events. Without this second transit detection we would have required many more radial-velocity measurements in order to confirm the planet, determine its orbital period, and measure its mass (e.g., Díaz et al. 2020). The strategy of large investments of photometric follow-up with instruments such as NGTS thereby allows efficient confirmation of single-transit events without adding to the considerable pressure on high-precision radial-velocity instruments. This highlights the power of high-precision ground-based photometric facilities in revealing longer-period transiting exoplanets that TESS alone cannot discover.

Many exoplanets discovered so far orbit very close to their stars, including hot Jupiters. Such objects are relatively easy to detect, but their nearness to their stars also makes them unlikely to be habitable. Finding more planets farther out from their stars, including those in their stars’ habitable zones, is important in the search for habitable worlds.

Telescopes like those at NGTS will help to find more habitable zone exoplanets, these scientists say.

Later, other telescopes like the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope – now scheduled for launch in October 2021 – will be able to analyze these planets’ atmospheres for possible biosignatures. By conducting research such as this, on Earth and in space, astronomers are stepping closer to finding other life in the galaxy, if it exists.

Bottom line: Astronomers rediscover a previously “lost” exoplanet that is relatively cool and close to its star’s habitable zone.

Source: NGTS-11 b (TOI-1847 b): A Transiting Warm Saturn Recovered from a TESS Single-transit Event