Update October 12, 2013. A journey to Jupiter is long and eventful, it seems. After a close flyby of Earth on Wednesday (October 9), where it received the gravity assist needed to send it on its way to the giant planet, NASA’s Juno spacecraft experienced a temporary glitch that sent the craft into safe mode. Space scientists were no doubt doing some nail biting at that time. But, yesterday afternoon (October 11), scientists at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio announced that Juno is now out of safe mode and has now resumed full flight operations.

According to their press release:

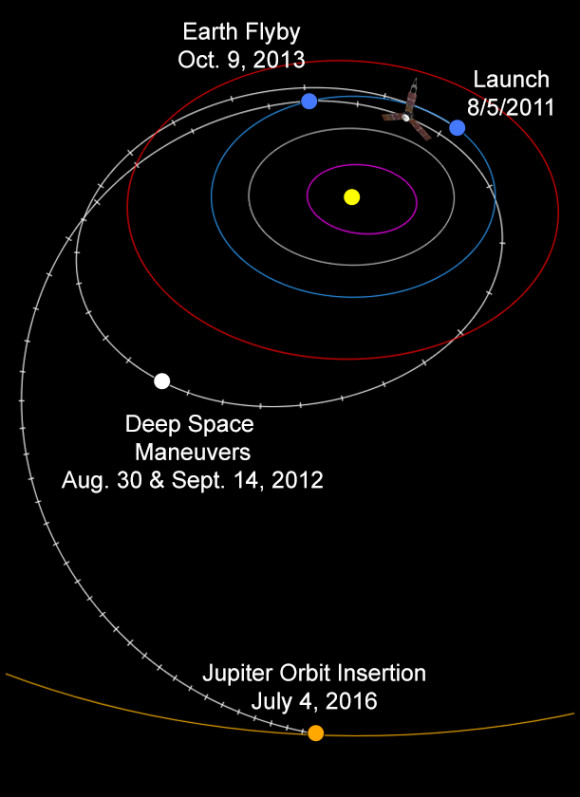

The safe mode did not impact the spacecraft’s trajectory one smidgeon. This flyby provided the necessary gravity boost to accurately slingshot the probe towards Jupiter, where it will arrive on July 4, 2016.

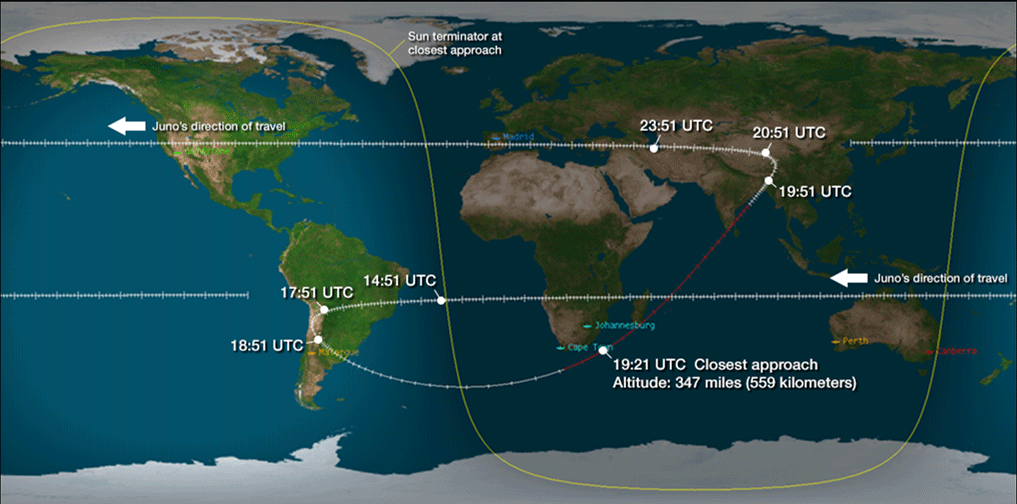

On October 9, Juno past within 350 miles of the ocean just off the tip of South Africa at 3:21 p.m. EDT (12:21 PDT / 19:21 UTC). Soon after closest approach, a signal was received by the European Space Agency’s 15-meter antenna just north of Perth, Australia, indicating the spacecraft initiated an automated fault-protection action called “safe mode.”

Safe mode is a state that the spacecraft may enter if its on-board computer perceives conditions on the spacecraft are not as expected. Onboard Juno, the safe mode turned off instruments and a few non-critical spacecraft components, and pointed the spacecraft toward the Sun to ensure the solar arrays received power. The spacecraft acted as expected during the transition into and while in safe mode.

Image via NASA / JPL / MSSS via the Planetary Society.

October 9, 2013. NASA’s Juno spacecraft will speed past Earth, coming only 347 miles (558 km) of our planet, on Wednesday, October 9, 2013. The craft – which is due to arrive in Jupiter’s vicinity in July 2016 – will use Earth’s gravity in a gravity assist to gain momentum for its long journey to Jupiter. The Juno spacecraft will be closest to Earth at 19:21 UTC (3:21 p.m. EDT) on Wednesday. You won’t be able to see the craft, but amateur radio operators around the world have been invited by NASA to say “hi” to Juno in a coordinated Morse code message.

When we say it’s speeding past Earth, we do mean speeding. Juno will be moving at a speed of 25 miles per second (40 km per second) relative to the sun. That’s in contrast to Earth’s own speed in orbit of 18 miles per second (30 km per second).

Bill Kurth, University of Iowa research scientist and lead investigator for one of Juno’s nine scientific instruments, commented in a press release:

… it will need every bit of this speed to get to Jupiter for its July 4, 2016, capture into polar orbit about Jupiter.

He added of the craft journey since its 2011 launch:

The first half of its journey has been simply to set up this gravity assist with Earth.

Although we won’t be able to see Juno sweep past with the eye alone, the craft won’t be far outside the range of visibility to the eye, in contrast to many other objects observed with backyard telescopes. And yet it’s also unlikely that telescopes will pick up the Juno spacecraft, due to the fast speed at which it’ll be traveling. SpaceWeather.com reported:

Estimates of its maximum brightness range from magnitude +7.5 to +8.5. Such a faint object moving rapidly across the sky will be a challenge for even large backyard telescopes. There is a slim chance, however, that sky watchers could see a “Juno flare” if sunlight glints off the spacecraft’s large solar arrays.

What are your chances of seeing it? Small. Still, HeavensAbove is offering finder charts, specific to your location on the globe. Click here to visit HeavensAbove’s Juno spacecraft page.

Scott Bolton, principal investigator for the Juno mission at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, told SpaceWeather.com that Juno’s science instruments will be activated to sample the Earth environment – a practice run for data-taking when the spacecraft reaches Jupiter in 2016. Bolton also said:

One of Juno’s activities during the Earth flyby will be to make a movie of the Earth-moon system that will be the first to show Earth spinning on its axis from a distance.

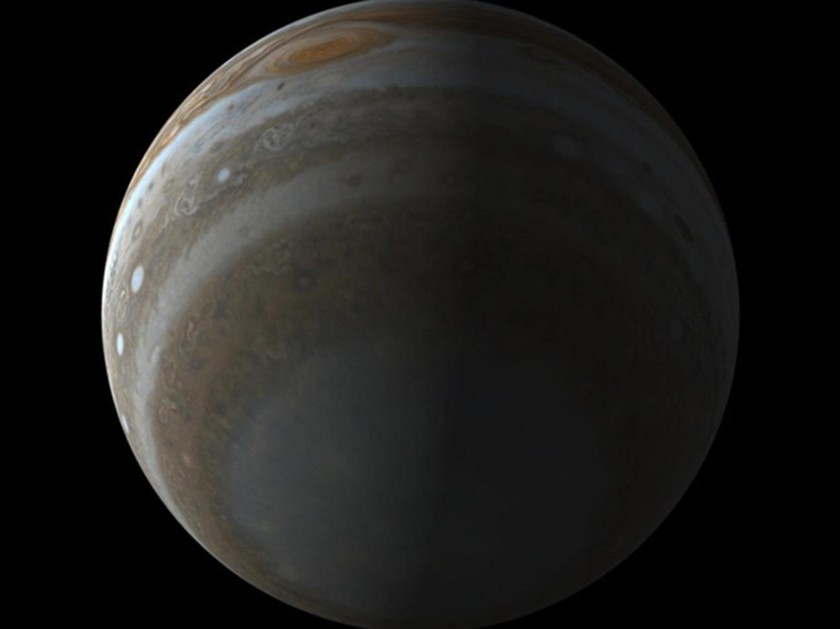

These scientists and others say the real science will begin when Juno begins orbiting Jupiter some 33 times over the course of a year. Juno will be the first spacecraft to orbit Jupiter over its poles. The orbit will be highly eccentric, taking Juno from just above the cloud tops to a distance of about 1.75 million miles from Jupiter, every 11 days.

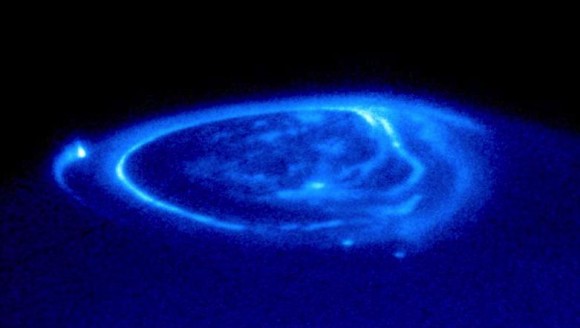

In particular, Juno will explore the solar system’s most powerful auroras – Jupiter’s northern and southern lights – by flying directly through the electrical current systems that generate them.

Juno’s other objectives including understanding the origin and evolution of Jupiter by:

– Determining the amount of water and ammonia present in the atmosphere.

– Observing the dynamics of Jupiter’s upper atmosphere.

– Mapping the planet’s magnetic and gravity fields to learn more about its deep interior, including the size of its core.

Scientists hope the insights gained from Juno’s explorations will help them understand more about how our own Earth evolved.

Juno’s destiny is a fiery entry into Jupiter’s atmosphere at the end of its one-year science phase as a means of guaranteeing it doesn’t impact Europa and possibly contaminate that icy world with microbes from Earth. This would jeopardize future missions to that moon designed to determine whether life had begun there on its own.

Bottom line: The Juno spacecraft – launched in 2011 in a roundabout journey toward Jupiter – will sweep only 347 miles (558 km) of Earth on Wednesday, October 9, 2013. The craft, which will be moving at 25 miles per second (40 km per second), will not be visible to the eye.