Webb catches the Tarantula Nebula

On September 6, 2022, NASA and ESA released new images of the Tarantula Nebula, aka 30 Doradus. It’s located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of our Milky Way, some 160,000 light-years away. The new Webb images peer into the star-forming heart of the Tarantula Nebula. The blue stars in a cluster at the center of the image above are young, hot and massive. They’re newly born in the Tarantula Nebula … And a very special sight.

Why special? It’s that – because Webb can see in the infrared – it can pierce the veil of the Tarantula Nebula’s clouds, to see clearly what’s inside the clouds. And it’s that the blue stars we find there are so hot and so massive that they’ll live only millions of years, instead of billions like our sun. Because they don’t live long, young, hot, blue stars aren’t as common as cooler, redder stars. Blue stars live out their short lives quickly, on the timescale of stars, and quickly explode as supernovae.

So seeing them, especially in a cluster like this, is a treat! And it also helps illustrate a time in our universe called cosmic noon by astronomers.

The Tarantula Nebula and cosmic noon

So the new Webb image of the Tarantula Nebula tells us about a massive star-forming region in the nearby universe. We see it 160,000 light-years away, and so 160,000 years ago. But it’s a nearby example of what must have been happening in the universe billions of years ago, during what’s sometimes called the cosmic noon of our universe. That’s astronomers’ name for a time when the universe was only 2 to 3 billion years old (in contrast to its current age of some 14 billion years).

Cosmic noon was the time in our universe when star formation peaked. Our Milky Way doesn’t have a region of fast and furious star formation, like that in the Tarantula Nebula. So, studying the Tarantula Nebula is a way glimpsing, on a small scale, what the whole universe must have been like, billions of years ago.

You have to image a whole universe of newly forming stars, with the hot, massive, blue stars – like those we see in the Tarantula Nebula – popping off as supernovae after only millions of years!

Eventually, astronomers will be able to compare Webb’s images of the Tarantula Nebula with images of star-forming regions it sees in the much-younger (more distant) universe.

Two space telescopes, twice the star power.

This #TransformationalTuesday, watch as @NASAHubble’s view of the Tarantula Nebula fades into Webb’s NIRCam, then MIRI instrument views. Hubble and Webb will work together to showcase the universe across multiple wavelengths of light. pic.twitter.com/GDIRSWWFQV

— NASA Webb Telescope (@NASAWebb) September 6, 2022

The Tarantula Nebula

The Tarantula Nebula lies 161,000 light-years distant in the Large Magellanic Cloud, which is in the Southern Hemisphere constellation of Dorado the Goldfish. That’s why the Tarantula Nebula is sometimes called 30 Doradus. This cloudy, dusty stellar nursery is home to the hottest, most massive stars known.

The Tarantula Nebula is not only home to the largest and brightest star-forming region in the Large Magellanic Cloud, but also in our Local Group, our regional collection of galaxies.

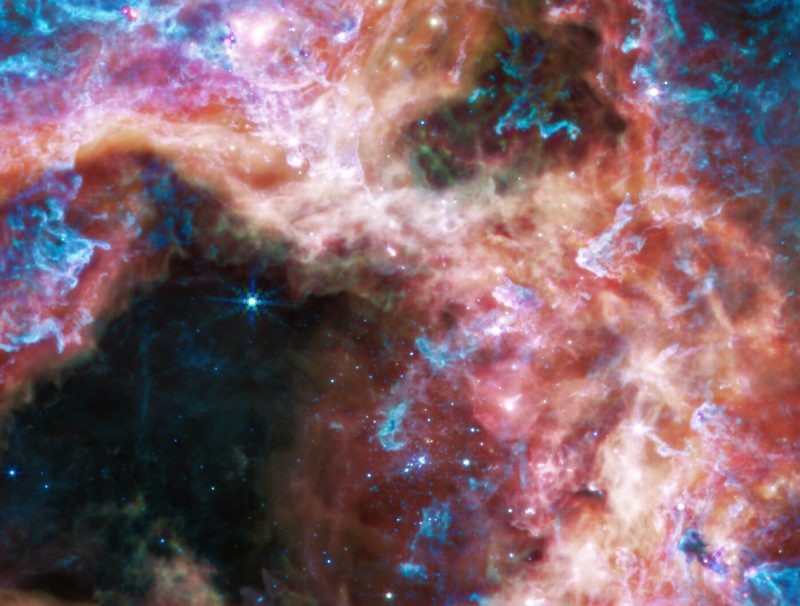

NIRCam’s view of the Tarantula

The image at the top of this article was acquired by the Webb’s NIRCam instrument. It shows the near-infrared view of the Tarantula. The hollowed-out region at center shows where fierce radiation from the young, hot, blue stars have cleared the area. Along with these young, massive stars – sparkling in pale blue – ESA said:

Only the densest surrounding areas of the nebula resist erosion by these stars’ powerful stellar winds, forming pillars that appear to point back toward the cluster. These pillars contain forming protostars, which will eventually emerge from their dusty cocoons and take their turn shaping the nebula.

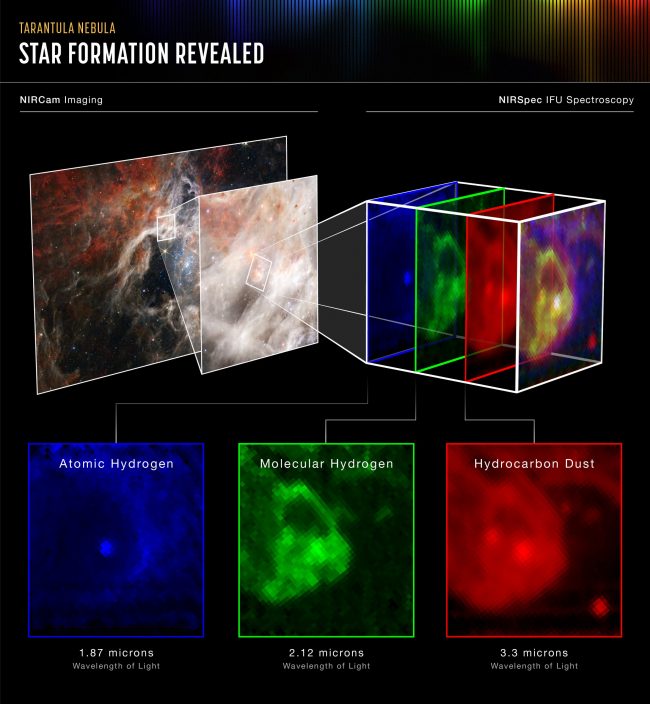

NIRSpec’s view of the Tarantula

NIRSpec is Webb’s Near InfraRed Spectrograph. And the spectrograph spreads light into a spectrum, which allows astronomers to investigate the object’s temperature, mass and chemical composition, for example. So, the young star NIRSpec focused on in the Tarantula Nebula is not yet at the stage where it’s clearing out the space around itself.

MIRI’s view of the Tarantula

The longer infrared wavelengths that another instrument – the MIRI instrument – sees let us look deeper into the Tarantula Nebula. So, now we can see cooler areas, where protostars are still gaining mass.

Bottom line: The James Webb Space Telescope has captured images of the Tarantula Nebula, revealing stellar nurseries and protostars. This star-forming region lies in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way.