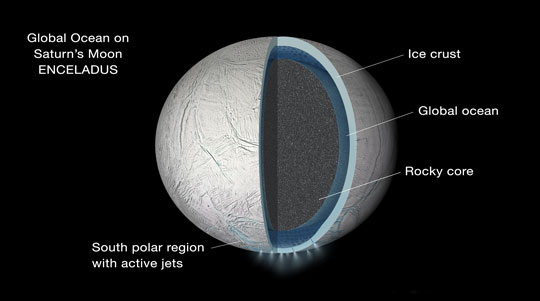

This week (September 15, 2015) scientists announced that, yes, a global ocean does exist beneath the icy crust of Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

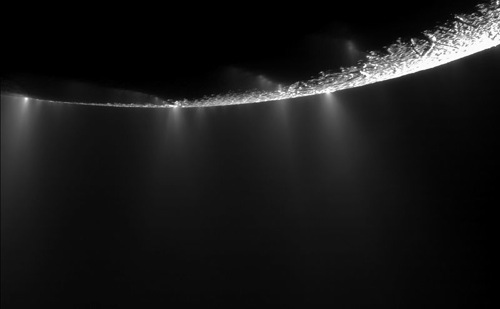

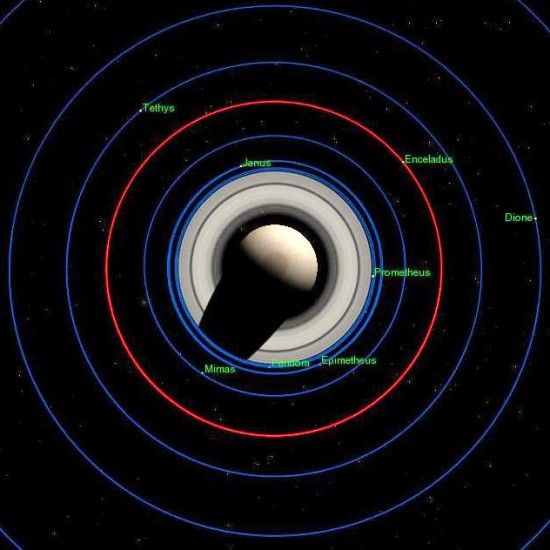

The Cassini spacecraft began orbiting the Saturn system in 2004, weaving in and among its many moons, and, in 2006, Cassini sent startling images back to Earth showing Enceladus spewing water vapor and ice from fractures at its South Pole. The fractures later were dubbed tiger stripes by scientists, and the water and ice plumes are known as geysers. Measurements of the saltiness of the geysers in 2009 showed that they must spew from a liquid underground reservoir. In early 2014, scientists announced a geophysical model for a hidden ocean inside Enceladus, based on an analysis of Enceladus’ gravitational pull on the Cassini spacecraft. In mid-2014 – again using data from Cassini – a map of 101 distinct geysers erupting from Enceladus’ surface confirmed the idea of a large regional or global ocean.

Now it’s the global aspect of the ocean that has been proven, and, once again, it’s the Cassini spacecraft that has provided scientists with this insight. They’ve found that Enceladus has a slight wobble – called a libration – as it orbits Saturn, which they can explain only if the outer crust floats freely from the inner core. This must mean an ocean under Enceladus’ icy surface, they say. This work is published online this month in the journal Icarus.

Matthew Tiscareno in Mountain View, California – whose role in this work was to develop a series of computer models describing the observed wobble of Enceladus – said in a statement from his home base, the SETI Institute:

If the surface and core were rigidly connected, the core would provide so much dead weight that the wobble would be far smaller than we observe it to be. This proves that there must be a global layer of liquid separating the surface from the core.

This exciting discovery expands the region of habitability for Enceladus from just a regional sea under the South Pole to all of Enceladus.

The global nature of the ocean likely tells us that it has been there for a long time, and is being maintained by robust global effects, which is also encouraging from the standpoint of habitability.

Peter Thomas, a Cassini imaging team member at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York is lead author of the new study. His team tested Tiscareno’s computer models against hundreds of Cassini images, taken of Enceladus’ surface at different times and from different angles, to find the best fit to the observations with extreme precision. A statement from Cornell explained that:

With each Cassini photographic pass, Thomas and others painstakingly pinpointed and measured Enceladus’ topographic features – about 5,800 points – by hand.

A slight wobble, about a tenth of a degree, was detected, but even this small motion … is far larger than if the surface crust were solidly connected to the satellite’s rocky core.

Thus, the scientists determined that the satellite must have a global liquid layer, far more extensive than the previously inferred regional liquid ‘sea’ beneath the South Pole.

These scientists point out that the geysers deliver samples from this hidden ocean to Enceladus’ surface, regularly. They say that makes Enceladus a prime candidate in the search for life beyond Earth. Although a handful of worlds are now thought to have subsurface oceans, Enceladus joins only Jupiter’s moon Europa (which was recently selected as the destination of NASA’s next flagship mission) in having an extraterrestrial ocean that is known to communicate with its surface.

Carolyn Porco, Cassini imaging team lead at Space Science Institute, Boulder, Colorado, and visiting scholar at the University of California, Berkeley, is also a coauthor on this new paper. She said:

This is a major step beyond what we understood about this moon before, and it demonstrates the kind of deep-dive discoveries we can make with long-lived orbiter missions to other planets.

Bottom line: Enceladus – a moon of the planet Saturn – has active water and ice geysers on its surface, discovered by the Cassini spacecraft in 2006. Since that discovery, scientists have speculated about the source of the geysers. This week (September 15, 2015), they announced that the geysers spew from a planet-wide, liquid ocean beneath the icy crust on this fascinating Saturn moon.