By Rasmus Rørbæk & Christoffer Karoff, Aarhus University, Denmark

Every now and then, large solar storms strike the Earth, where they cause auroras and in rare cases, power cuts. These events are, however, nothing compared to the apocalyptic destruction we would experience if the Earth were struck by a superflare. An international research team suggests that this scenario might be a real possibility.

Solar eruptions consist of energetic particles that are hurled away from the sun into space, where those directed towards Earth encounter the magnetic field around our planet. When these eruptions interact with Earth’s magnetic field they cause beautiful auroras – a poetic phenomenon that reminds us that our closest star is an unpredictable neighbor.

Solar eruptions are, however, nothing compared to the eruptions we see on other stars, the so-called ‘superflares’. Superflares have been a mystery since the Kepler mission discovered them in larger numbers four years ago.

Questions arose: Are superflares formed by the same mechanism as solar flares? If so, does that mean that the sun is also capable of producing a superflare?

An international research team has now suggested answers to some of these questions. Their alarming answers were published in Nature Communications on March 24, 2016.

The dangerous neighbor

The sun is capable of producing monstrous eruptions that can break down radio communication and power supplies here on Earth. The largest observed eruption took place in September 1859, when gigantic amounts of hot plasma from our neighboring star struck Earth.

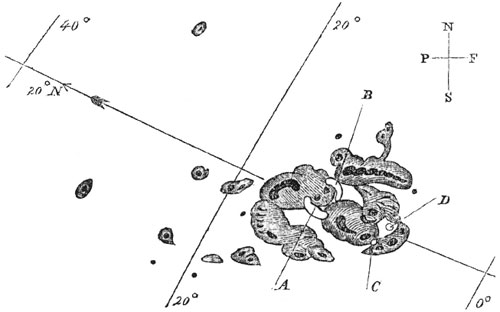

On September 1, 1859, astronomers observed how one of the dark spots on the surface of the sun suddenly lit up and shone brilliantly over the solar surface. This phenomenon had never been observed before and nobody knew what was to come. On the morning of September 2, the first particles from what we now know was an enormous eruption on the sun, reached Earth.

The 1859 solar storm is also known as the “Carrington Event.” Auroras associated with this event could be seen as far south as Cuba and Hawaii. Telegraph system worldwide went haywire. Ice core records from Greenland indicate that Earth’s protective ozone layer was damaged by the energetic particles from the solar storm.

The cosmos, however, contains some stars that regularly experience eruptions that can be up to 10,000 times larger than the Carrington event.

Solar flares occur when large magnetic fields on the surface of the sun collapse. When that happens, huge amounts of magnetic energy are released. The researchers used observations of magnetic fields on the surface of almost 100,000 stars made with the new Guo Shou Jing telescope in China to show that these superflares are likely formed via the same mechanism as solar flares.

Lead researcher Christoffer Karoff from Aarhus University, Denmark, said:

The magnetic fields on the surface of stars with superflares are generally stronger than the magnetic fields on the surface of the sun. This is exactly what we would expect if superflares are formed in the same way as solar flares.

Can the sun create a superflare?

It does therefore not seem likely that the sun should be able to create a superflare, its magnetic field is simply too weak. However…

Out of all the stars with superflares that the team analyzed, around 10% had a magnetic field with a strength similar to or weaker than the sun’s magnetic field. Therefore, even though it is not very likely, it is not impossible that the sun could produce a superflare. Karoff said:

We certainly did not expect to find superflare stars with magnetic fields as weak as the magnetic fields on the sun. This opens the possibility that the sun could generate a superflare – a very frightening thought.

If an eruption of this size were to strike Earth today, it would have devastating consequences. Not just for all electronic equipment on Earth, but also for our atmosphere and thus our planet’s ability to support life.

Trees hid a secret

Evidence from geological archives has shown that the sun might have produced a small superflare in 775 AD. Tree rings show that anomalously large amounts of the radioactive isotope 14C were formed in Earth’s atmosphere at that time. Isotope 14C is formed when cosmic ray particles from our galaxy, the Milky Way, or especially energetic protons from the sun, formed in connection with large solar eruptions, enter Earth’s atmosphere.

The studies from the Guo Shou Jing telescope support the notion that the event in 775 AD was indeed a small superflare – a solar eruption 10-100 times larger than the largest solar eruption observed during the space age. Karoff said:

One of the strengths of our study is that we can show how astronomical observations of superflares agree with Earth-based studies of radioactive isotopes in tree rings.

In this way, the observations from the Guo Shou Jing telescope can be used to evaluate how often a star with a magnetic field similar to the sun would experience a superflare. The new study shows that the sun, statistically speaking, should experience a small superflare every millennium. This is in agreement with idea that the event in 775 AD and a similar event in 993 AD were indeed caused by small superflares on the sun.

Enjoying EarthSky? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Bottom line: An international research team has suggested that our sun could be a superflare star. Their findings were published in Nature Communications on March 24, 2016.