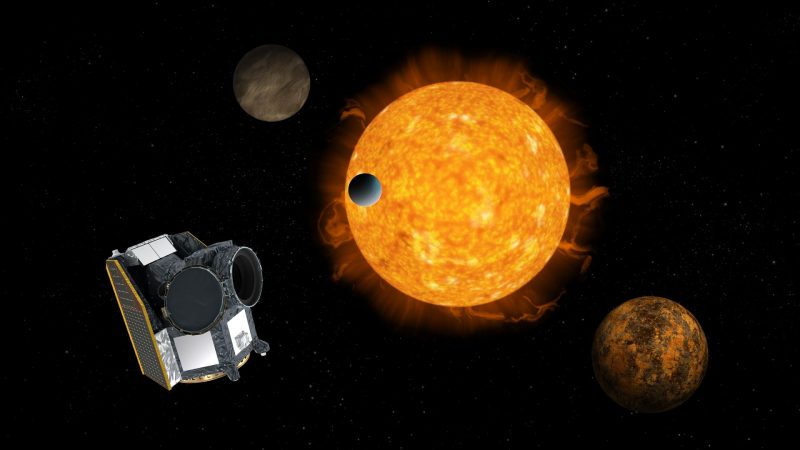

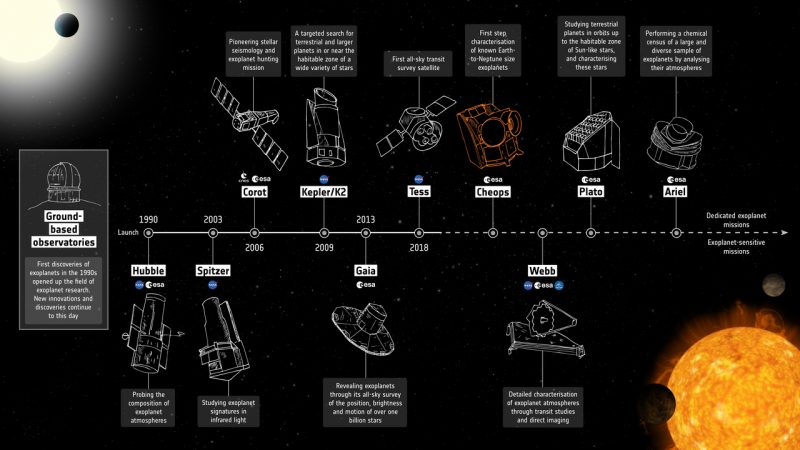

After a one-day delay, the European Space Agency (ESA) successfully launched its CHEOPS mission last week, on the morning of December 18, 2019, from the spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. CHEOPS is the first ESA mission dedicated to studying exoplanets, those distant worlds orbiting other stars. NASA’s planet-hunting space missions, first Kepler and now TESS, have been finding new exoplanets. CHEOPS will study hundreds of exoplanets already known to exist – out of 4,000-plus now confirmed – to determine their sizes, masses, densities and possible atmospheres.

In this way, CHEOPS will take us some steps along the road of finding out what many exoworlds are actually like, not an easy task.

CHEOPS stands for CHaracterising ExOPlanets Satellite. The telescope will reside in a sun-synchronous orbit around Earth at an altitude of more than 400 miles (700 km). Kate Isaak, CHEOPS project scientist, said in a statement:

We are very excited to see the satellite blast off into space. There are so many interesting exoplanets and we will be following up on several hundreds of them, focusing in particular on the smaller planets in the size range between Earth and Neptune. They seem to be the commonly found planets in our Milky Way galaxy, yet we do not know much about them. CHEOPS will help us reveal the mysteries of these fascinating worlds, and take us one step closer to answering one of the most profound questions we humans ponder: are we alone in the universe?

Watch the launch below:

Heike Rauer, Director of the DLR Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin, said:

More than 4000 exoplanets have been discovered in the Milky Way, yet we still know far too little about these distant worlds in our cosmic neighborhood. We are all eager to see which ‘faces’ the planets characterized by CHEOPS will show us.

So how does CHEOPS observe these planets?

Like some other telescopes, it will watch as the planets transit in front of their stars, as seen from Earth. As Juan Cabrera Perez, Head of the Extrasolar Planets and Atmospheres Department at the DLR Institute of Planetary Research, explained:

We could describe this fluctuation in brightness as a ‘mini stellar eclipse’, as the transiting exoplanet reduces the intensity of the light from the star for a short time. This fluctuation can be measured and analyzed – an area in which we can contribute suitable tools and many years of experience.

EarthSky 2020 lunar calendars are available! They make great gifts. Order now. Going fast!

CHEOPS will focus on some of the most common exoplanets discovered so far, ranging in size from Earth to Neptune, or about approximately 6,000 to 30,000 miles (10,000 to 50,000 km) in diameter. Using data from the transits, CHEOPS can determine the size, mass and density of the planets. All of these are important in order for scientists to figure out the planets’ compositions. Some will be rocky like Earth, while others will have deep, gaseous atmospheres like Neptune or even Jupiter or Saturn. Knowing this will also help scientists determine which of these worlds might be potentially habitable. Of course, rocky planets similar in size to Earth, or a bit larger – super-Earths – would be the most interesting in this regard. Nicola Rando, CHEOPS project manager, said:

Both CHEOPS instrument and spacecraft are built to be extremely stable, so as to measure the incredibly small variations in the light of distant stars as their planets transit in front of them. For a planet like Earth, this amounts to the equivalent of watching the sun from a distant star and measuring its light dim by a tiny fraction of a percent. Now we are looking forward to the first part of the operational activities, making sure that the satellite and instrument perform as expected, ready for scientists to perform their world-class science.

CHEOPS will also be able to find out which of these planets do have atmospheres and whether they have clouds. This will help differentiate between deep, gaseous primordial atmospheres with no real solid surface beneath them, and thinner atmospheres like those on terrestrial planets such as Earth, Venus or Mars.

CHEOPS is just the first of three planned ESA missions to study exoplanets.

The Planetary Transits and Oscillations of stars (PLATO) space telescope, expected to launch in 2026, will focus on searching for “Earth-like” planets, ones that are rocky and about the same size as Earth orbiting in their stars’ habitable zones. So far, most such worlds have been found orbiting red dwarf stars, the most common type of star in our galaxy. CHEOPS, however, will look for these planets around sun-like stars. It will also be able to determine the age of these planetary systems with more accuracy than possible before.

A couple of years later, in 2028, ESA will launch the Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey (ARIEL) mission, which will study the atmospheres of exoplanets. As well as atmospheric composition, this will help scientists develop a comprehensive catalog of exoplanetary orbits, radii, masses, densities and ages.

All three of these exciting missions, and others, will greatly increase our knowledge of these exotic, far-off worlds.

As Günther Hasinger, ESA Director of Science, said:

CHEOPS will take exoplanet science to a whole new level. After the discovery of thousands of planets, the quest can now turn to characterization, investigating the physical and chemical properties of many exoplanets and really getting to know what they are made of and how they formed. CHEOPS will also pave the way for our future exoplanet missions, from the international James Webb Telescope to ESA’s very own PLATO and ARIEL satellites, keeping European science at the forefront of exoplanet research.

The CHEOPS mission is a partnership between ESA and Switzerland with additional contributions from Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the U.K. More than 100 scientists and engineers are involved. The nominal mission is expected to last 3 1/2 years. While the CHEOPS science team has the bulk of observation time, 20% of the time is reserved for other scientists from around the world.

CHEOPS and the coming follow-up missions will open an exciting new chapter in exoplanetary study. What fascinating discoveries will they make?

Bottom line: ESA has successfully launched its CHEOPS space telescope to study hundreds of exoplanets in more detail than ever before.