Have you heard people say that NASA lies, or that scientists are just chasing grants, or even that science itself is broken or in crisis? We at EarthSky often hear these comments, and, while they don’t surprise us anymore, we do ponder the general public’s perception of science, especially given the public debate in the U.S. over climate change and other science-related issues, and especially in a media climate that allows fake news. This month (March 12, 2018), in the peer-reviewed Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), communications scholar Kathleen Hall Jamieson documented three alternative news narratives about science.

She argued that science isn’t broken or in crisis. And she said it’s the job of the media to educate people about how science works.

Science was once so respected in America that Helena Rubinstein wore a lab coat in her cosmetics ads. @JewishMuseumNY pic.twitter.com/yx4k44qJQq

— Deborah Solomon (@deborahsolo) October 30, 2014

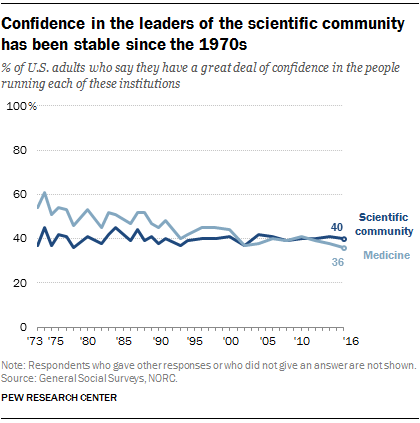

First, what is the public’s perception of science? Has that perception deteriorated? This short article at the Pew Research Center – from April, 2017 – suggests it hasn’t and that, in fact:

… public confidence in science has remained stable for decades.

However, Pew said, a segment of the U.S. population (6 percent) has “hardly any confidence” in the scientific community. Pew is basing its conclusion on data collected by NORC, an independent research organization at the University of Chicago, whose General Social Survey (GSS) has been running each year since 1972. Pew said GSS results released a year ago – on March 29, 2017 – show:

… that 40 percent of Americans have a great deal of confidence in the scientific community, while half (50 percent) have only some confidence and 6 percent have hardly any confidence.

Public confidence in scientists stands out among the most stable of about 13 institutions rated in the GSS survey since the mid-1970s.

Despite these survey results, Kathleen Hall Jamieson and others worry about a public perception of science as broken. Jamieson is a communications professor and director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania. This academic center runs FactCheck.org, which examines the factual accuracy of U.S. political campaign advertisements. She and Joe Hilgard of Illinois State University contributed a chapter to The Oxford Handbook of the Science of Science Communication, published in 2017. Their chapter was titled Science as “Broken” Versus Science as “Self-Correcting.”

What does it mean for science to be self-correcting?

In her March 12 essay, Jamieson outlined three narratives used by the media in science stories. She included the quest discovery narrative, the counterfeit discovery narrative and the systemic problem narrative (the overall idea that science is broken).

Quest discovery, she said, is a classic literary genre used from Gilgamesh to The Lord of the Rings.

In typical quest discovery stories about science, you’ll find words like advance, path-breaking, breakthrough, or discovery.

Jamieson pointed out that this narrative is employed particularly when presenting science that’s useful to humankind. And many science stories do lean that way. Of the 60 studies that received the most media coverage from May 2016 to April 2017, she wrote, nearly half were related to human health and well-being, according to the tracking firm Altmetric.

On the other hand, Jamieson said, the media also frequently employs a counterfeit discovery narrative. We’ve all read this story. It’s the tale of a deceptive scientist and a dishonorable quest, the story of someone who has “gulled custodians of knowledge” such as science journal editors and peer reviewers. Jamieson provided an interesting sequence of headlines related to Haruko Obokata, who reported having developed a method of developing pluripotent stem cells. The sequence started with:

Study says new method could be a quicker source of stem cells, The New York Times, January 9, 2014.

And Obokata’s story quickly deteriorated in the media, ending (in Jamieson’s sequence) less than a year later with:

Stem cell scandal scientist Haruko Obokata resigns, BBC News, December 19, 2014.

In recent years, the soft science of psychology has been riddled with counterfeit discovery headlines. Jamieson pointed to The Atlantic’s March 2016 article titled Psychology’s replication crisis can’t be wished away, for example. Jamieson commented:

Indictments of null hypothesis testing and P values [both commonly used in psychology] were rationalized away as well. Such inaction warranted “broken, uncorrecting” and perhaps even “crisis” characterizations, and the inference that such terms were more realistic than histrionic.

In other words, some sciences – such as psychology – may have their own unique and troublesome issues.

The psychology example feeds into Jamieson’s argument that the third narrative – science is broken – is an overgeneralization. Yet, in media today, many stories do suggest science as a whole (or in some large part) is broken. You can find stories like that here and here and here and here. Jamieson also pointed to some science writers today, who tend to concentrate on what she calls a problem-focused news narrative in science, with headlines and storylines to match. She said:

In such accounts, scientists are portrayed as publicizing problems, not proffering solutions.

Jamieson doesn’t think science is broken. She stated in her essay:

… generalizations about a crisis in science aren’t justified by the available evidence.

But she thinks the issue is important, because news media portrayals of science affect how we all think about it. That’s why she concluded that:

… those who communicate science, including journalists, scholars, and scientists themselves, should more accurately convey its investigatory nature, the self-correction process, and corrective measures without legitimizing a faulty narrative.

By the way, Jamieson identified ways that science narratives can be improved in the media. Among her suggestions:

Include information that reflects the practices and protections of science, such as the trial-and-error process, and the ways that science detects and protects itself from deception;

Reserve “dire characterizations of the state of science” for cases in which “integrity-threatening problems are being ignored”;

Treat self-correction as a central part of the scientific process, not an afterthought – before regarding a rise in retractions as a “crisis in science,” consider the argument that they are a “signal that science is working”;

Focus on problems without shortchanging solutions: “To perform their accountability function well, reporters should not only alert the public to problems in consequential science but also scrutinize how and how well they are being addressed.”

Her essay concluded:

By responsibly publicizing both breaches of integrity and attempts to forestall them, news can perform its accountability function without undermining public trust in the most reliable form of knowledge generation humans have devised.

Bottom line: Kathleen Jamieson analyzed narratives used in media to portray science. She argued that science isn’t broken or in crisis and that it’s the job of the media to educate people about how science works.