An innovative analysis of tiger shark tracking data, spanning seven years, has revealed that pregnant female tiger sharks migrate from the northwestern Hawaiian Islands to populated main islands from September to early November each year. This time period coincides with the birthing season of tiger shark pups, as well as higher occurrences of shark attacks in waters around the main islands. A paper about this newly-discovered migration pattern will be published in the November 2013 issue of the journal Ecology by scientists from the University of Florida and the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Yannis Papastamatiou, a marine biologist at the Florida Museum of Natural History, on the University of Florida campus, said in a press release:

We have previously analyzed data to see which sharks are hanging around shark tours with cage divers on Oahu, and one of the things we noticed was that you’d get a spike in how many tiger sharks are seen in October, which would match our predicted model that you’re having an influx of big, pregnant females coming from the northwestern Hawaiian Islands. There even tends to be a spike in the number of shark bites that occur during that season.

Tiger sharks, among the largest ocean predators, are found worldwide in tropical and temperate waters. Adult males can measure as much as 9 feet long, and females can reach a length of 11 feet. They prey on a wide variety of marine animals, such as crustaceans, fish, seals, birds, dolphins, and smaller sharks. Much remains unknown about their reproduction. Females are believed to give birth once every three years. The eggs hatch internally and embryos may remain in gestation for as long as 15 months. At birth, the pups are almost 3 feet in length.

At the Hawaiian Archipelago, tiger sharks are found year-round. In order to track and observe them, which is no easy feat at sea, sharks need to be “tagged.” This involves catching the shark, collecting information about its size, sex, and approximate age, then attaching a transmitter to the shark to track its movements. Each shark is assigned a unique transmission code so it can be individually tracked.

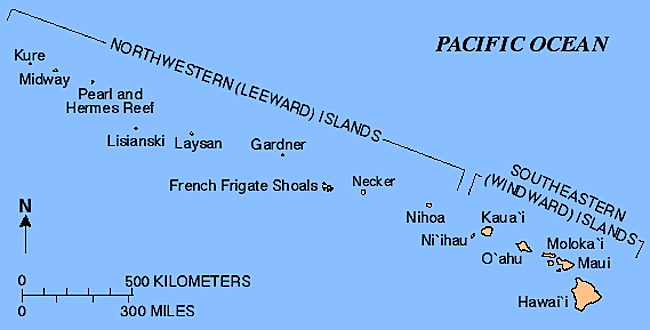

There are two types of tagging: satellite and passive acoustic telemetry. Satellite transmitters are useful for tracking over very large distances in the open ocean. For this study, however, most data came from passive acoustic telemetry tagging. Transmitters attached to the tiger sharks emit a high frequency code that’s unique for each animal. As the sharks travel amongst the islands of the Hawaiian Archipelago, that spans over 1,500 miles, the movements of each individual is picked up by one of 143 underwater receiving stations that are positioned at islands and atolls along the island chain. Each shark transmitter tag lasts about 3 years. Since 2004, more than 100 tiger sharks have been tracked using this system.

Said Papastamatiou in the same press release,

We believe approximately one-quarter of mature females swim from French Frigate Shoals atoll to the main Hawaiian Islands in the fall, potentially to give birth. However, other individual sharks will also swim to other islands, perhaps because they are trying to find a more appropriate thermal environment, or because there may be more food at that island. So, what you see is this complex pattern of partial migration that can be explained by somewhat fixed factors, like a pregnant female migrating to give birth in a particular area, and more flexible factors such as finding food.

Migration of female tiger sharks from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands to the more populated main Hawaiian islands like Oahu coincides with the tiger shark birthing season from September to early November, suggesting that the females are heading for waters more suited for the pups’ survival. There is another ominous coincidence; even though shark bites are rare, the most frequent incidences occur from October to December. Hawaiian lore even warns of this. Said Carl Meyer, of the University of Hawaii, a co-author of the paper, in another press releas:

Both the timing of this migration and tiger shark pupping season coincide with Hawaiian oral traditions suggesting that late summer and fall, when the wiliwili tree blooms, are a period of increased risk of shark bites.

Papastamatiou and Meyer, however, caution against concluding that migrating female tiger shark are the cause of increased shark bites around Maui, Oahu, and the Big Island from October to December. There are many factors influencing shark behavior that would bring them in close proximity to people, and there’s simply not enough data to show a link between the migrating females and shark attacks, especially considering the rarity of these attacks. Papastamatiou believes that the migration of female tiger sharks to waters around the main Hawaiian islands could be due to those locations being suitable nursery sites for tiger shark pups because these waters provide different types of prey, protection from ocean waves, and perhaps other reasons that have yet to be discovered.

One thing that the tagging data shows is that tiger sharks are not territorial, that they don’t linger along a specific coastline location for more than a few weeks. This evidence points to the futility of culling sharks in the vicinity of a shark attack because it’s quite likely that the culprit will not be among the dead sharks. Said Papastamatiou, regarding shark attacks,

The one thing I hope they don’t do is try to initiate a cull as was done in the ’60s and ’70s. I don’t think it works. There is no measurable reduction in attacks after a cull.

Bottom line: In a paper published in the November 2013 issue of Ecology, scientists from the University of Florida and the University of Hawaii at Manoa report on the migration of pregnant female tiger sharks from the French Frigate Shoals of northwestern Hawaii to the populated main Hawaiian islands, from September to early November each year. They discovered this pattern in an analysis of seven years worth of Hawaiian tiger shark tracking data. This period also coincides with the birthing season of tiger shark pups, and a higher rate of shark attacks in waters around the main Hawaiian islands. The scientists, however, caution against assuming a link between these events because very little is known about the behavior of sharks, the reasons for their migrations, as well as the circumstances under which shark attacks occur.