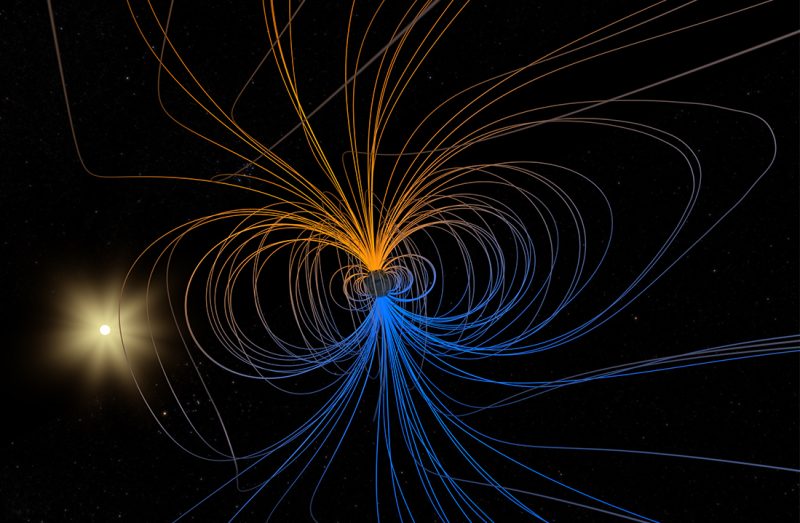

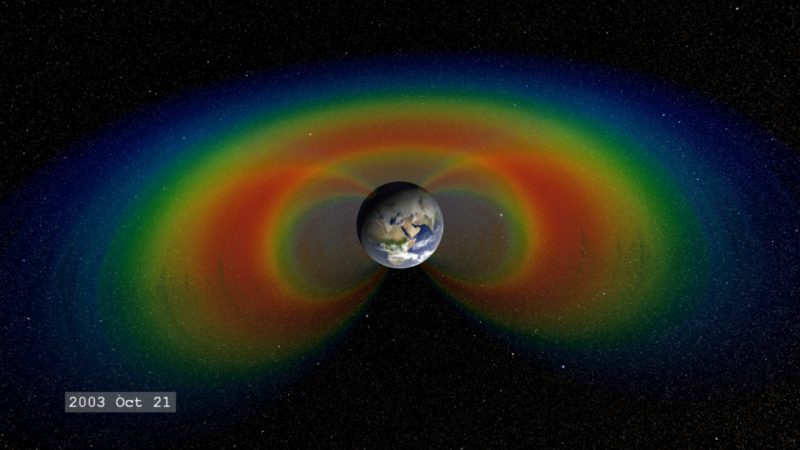

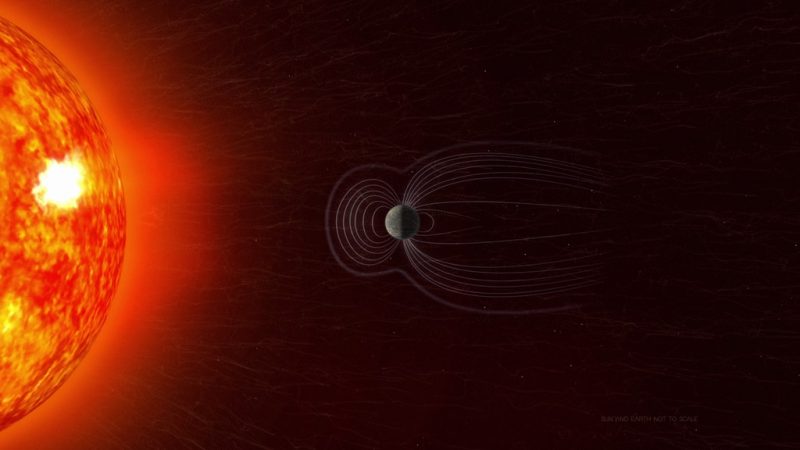

Earth’s magnetic field acts like a protective shield around the planet, repelling and trapping charged particles from the sun. But there’s an unusually weak spot in the field, a slowly expanding “dent” over South America and the southern Atlantic Ocean – called the South Atlantic Anomaly, or SAA – that allows these particles to dip closer to the surface than normal. The SAA developed as a result in changes to the motion of Earth’s core, according to an August 12, 2020, NASA statement.

Although the SAA arises from processes inside Earth, it has effects that reach far beyond Earth’s surface. Particle radiation in this region can knock out onboard computers and interfere with the data collection of satellites that pass through it. If a satellite is hit by a high-energy proton, it can short-circuit and cause an event called single event upset, or SEU. This can cause the satellite’s function to glitch temporarily or can cause permanent damage if a key component is hit. In order to avoid losing instruments or an entire satellite, operators commonly shut down non-essential components as they pass through the SAA.

And although the SAA currently creates no visible impacts on daily life on our planet’s surface, recent observations show that the region is expanding westward and continuing to weaken in intensity. It’s also splitting, say scientists. Recent data shows the anomaly’s valley, or region of minimum field strength, has split into two lobes, creating additional challenges for satellite missions.

The International Space Station (ISS), which is in low Earth orbit, also passes through the SAA. It is well protected, and astronauts are safe from harm while inside. However, the ISS has other passengers affected by the higher radiation levels: Instruments like the Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation mission, or GEDI, which collect data from various positions on the outside of the ISS. The SAA causes “blips” on GEDI’s detectors and resets the instrument’s power boards about once a month, said Bryan Blair, the mission’s deputy principal investigator and instrument scientist. Blair said:

These events cause no harm to GEDI. The detector blips are rare compared to the number of laser shots – about one blip in a million shots – and the reset line event causes a couple of hours of lost data, but it only happens every month or so.

A host of scientists in geomagnetic, geophysics, and heliophysics research groups observe and monitor the SAA to predict future changes, and help prepare for future challenges to satellites and humans in space. The South Atlantic Anomaly is also of interest to Earth scientists who monitor the changes in magnetic field strength there, both for how such changes affect Earth’s atmosphere and as an indicator of what’s happening to Earth’s magnetic fields deep inside the globe. Hear more from NASA scientists studying the SAA.

NASA geophysicist Terry Sabaka said in a statement:

Even though the SAA is slow-moving, it is going through some change in morphology [shape and structure], so it’s also important that we keep observing it by having continued missions. Because that’s what helps us make models and predictions.

Bottom line: Researchers are tracking a slowly splitting “dent” in Earth’s magnetic field, called the South Atlantic Anomaly or SAA.