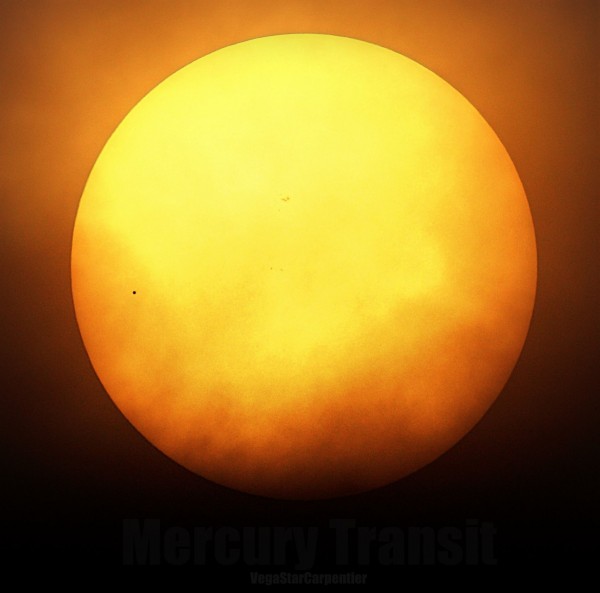

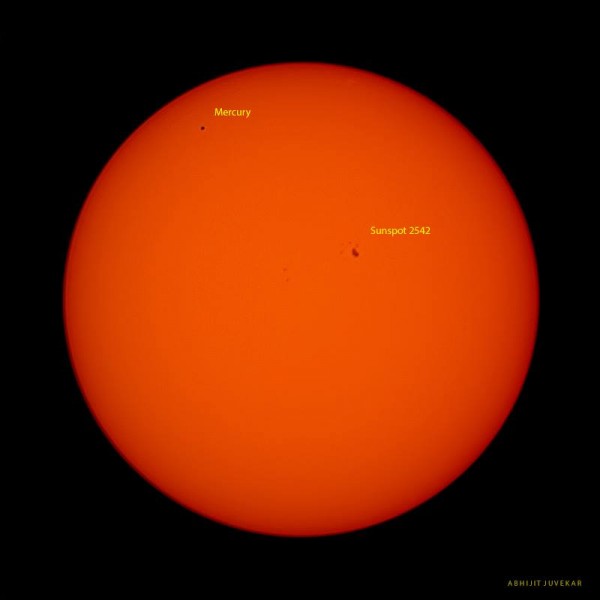

Photo at top: Mercury transit, May 9, 2016 via @altair_astro on Twitter. See more photos of the 2016 Mercury transit.

Mercury – the innermost planet of our solar system – will transit the sun on November 11, 2019. In other words, Mercury will pass directly in front of the sun and be visible through telescopes with solar filters as a small black dot crossing the sun’s face. It’ll be visible in part from most of Earth’s globe. The entire transit is visible from South America, eastern North America, and far-western Africa.

The last transit of Mercury was in 2016. The next one won’t be until 2032.

Be aware that this is a morning event on November 11, according to U.S. clocks. Mercury will come into view on the sun’s face around 7:36 a.m. Eastern Standard Time (12:36 UTC; translate UTC to your time) on November 11. It’ll make a leisurely journey across the sun’s face, reaching greatest transit (closest to sun’s center) at approximately 10:20 a.m. EST (15:20 UTC) and finally exiting around 1:04 p.m. EST (18:04 UTC). The entire 5 1/2 hour path across the sun will be visible across the U.S. East – with magnification and proper solar filters – while those in the U.S. West can observe the transit already in progress after sunrise.

You need a telescope and solar filters to view the transit. Mercury’s diameter is only 1/194th of that of the sun, as seen from Earth. That’s why the eclipse master Fred Espenak recommends using a telescope with a magnification of 50 to 100 times for witnessing the event.

Unless you are well-versed with the telescope and how to properly use solar filters, we advise you to seek out a public program via a nearby observatory or astronomy club. Never look at the sun through a telescope.

Click here to find a public presentation of the Mercury transit near you.

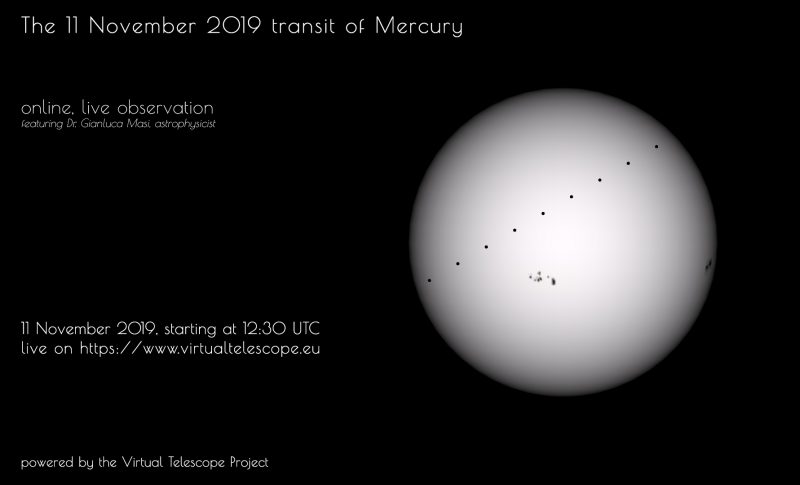

The Virtual Telescope Project in Rome is hosting an online transit-viewing session.

Guy Ottewell has a magnificent page on the November 11, 2019, Mercury transit

EarthSky 2020 lunar calendars are available! They make great gifts. Order now. Going fast!

What part of Earth will see the November 11 transit of Mercury? As shown on the worldwide chart above, the transit will be visible (at least in part) from most of the globe, with the exception of the shaded-out portion (Indonesia, most of Asia, and Australia). Mercury takes some 5 1/2 hours to cross the sun’s disk, and this transit of Mercury is entirely visible (given clear skies) from eastern North America, South America, the southern tip of Greenland, and far-western Africa.

For North America, the transit begins in the early morning hours on November 11. The eastern part of North America sees the start of the transit after sunrise November 11, whereas the western part sees the transit already in progress as the sun rises on November 11.

As for the world’s Eastern Hemisphere – Africa, Europe, and the Middle East – the transit starts in the early afternoon November 11 in the westernmost parts of Africa and Europe, and in the late afternoon November 11 in eastern Europe and the Middle East. In New Zealand, the transit is in process as the sun rises on November 12.

We provide the geocentric (Earth-centered) contact times of the transit of Mercury in Universal Time (UTC). If you know how to convert Universal Time to your local time (here’s how to do it), you can get a good approximation of the contact times for the Mercury transit for your part of the world. NOTE: Because the transit is viewed from the Earth’s surface, instead of the Earth’s center, the contact times could differ from the geocentric contact times by up to a minute.

Read more: How to safely observe the Mercury transit

Transit of Mercury on 11 November 2019, from Society for Popular Astronomy on Vimeo.

November 11 transit times in Universal Time

First contact (ingress, exterior): 12:35:27 UT

Second contact (ingress, interior): 12:37:08 UT

Greatest transit: 15:19:48 UT

Third contact (egress, interior): 18:02:33 UT

Fourth contact (egress, exterior): 18:04:14 UT

Want to know if and when the transit happens in your sky? Click here to find out your local transit times via timeanddate.com.

Mercury transit times for select North American cities in your local time

The times below are in your local time (meaning no conversion is necessary). We give transit contact times for various North American cities and Honolulu, Hawaii.

NOTE: All places within the same time zone have very similar contact times.

Newfoundland Standard Time (NST)

St. Johns, Newfoundland:

First contact (ingress, exterior): 9:05:56 a.m. NST

Second contact (ingress, interior): 9:07:38 a.m. NST

Greatest transit: 11:50:03 a.m. NST

Third contact (egress, interior): 2:32:33 p.m. NST

Fourth contact (egress, exterior): 2:34:14 p.m. NST

Atlantic Standard Time (AST)

Halifax, Nova Scotia:

First contact (ingress, exterior): 8:36:00 a.m. AST

Second contact (ingress, interior): 8:37:42 a.m. AST

Greatest transit: 11:20:08 a.m. AST

Third contact (egress, interior): 2:02:36 p.m. AST

Fourth contact (egress, exterior): 2:04:17 p.m. AST

Eastern Standard Time (EST)

New York City, New York:

First contact (ingress, exterior): 7:36:04 a.m. EST

Second contact (ingress, interior): 7:37:48 a.m. EST

Greatest transit: 10:20:13 a.m. EST

Third contact (egress, interior): 1:02:39 p.m. EST

Fourth contact (egress, exterior): 1:04:20 p.m. EST

Central Standard Time (CST)

New Orleans, Lousiana:

First contact (ingress, exterior): 6:36:08 a.m. CST

Second contact (ingress, interior): 6:37:49 a.m. CST

Greatest transit: 9:20:20 a.m. CST

Third contact (egress, interior): 12:02:45 p.m. CST

Fourth contact (egress, exterior): 12:04:26 p.m. CST

Mountain Standard Time (MST)

Denver, Colorado:

First contact (ingress, exterior): sun below horizon

Second contact (ingress, interior): sun below horizon

Greatest transit: 8:20:24 a.m. MST

Third contact (egress, interior): 11:02:54 a.m. MST

Fourth contact (egress, exterior): 11:04:35 a.m. MST

Pacific Standard Time (PST)

Los Angeles, California:

First contact (ingress, exterior): sun below horizon

Second contact (ingress, interior): sun below horizon

Greatest transit: 7:20:08 a.m. PST

Third contact (egress, interior): 10:03:00 a.m. PST

Fourth contact (egress, exterior): 10:04:41 a.m. PST

Alaska Standard Time (AKST)

Juneau, Alaska:

First contact (ingress, exterior): sun below horizon

Second contact (ingress, interior): sun below horizon

Greatest transit: 7:40:25 a.m. AKST

Third contact (egress, interior): 9:03:04 a.m. AKST

Fourth contact (egress, exterior): 9:04:45 a.m. AKST

Hawaii-Aleutian Standard Time HST)

Honolulu, Hawaii:

First contact (ingress, exterior): sun below horizon

Second contact (ingress, interior): sun below horizon

Greatest transit: sun below horizon

Third contact (egress, interior): 8:03:13 a.m. HST

Fourth contact (egress, exterior): 8:04:54 a.m. HST

Transit contact times for many more North American cities via Fred Espenak’s EclipseWise.com:

Need more? More world transit times from timeanddate.com

How common are transits of Mercury? Although much more common than transits of Venus, a transit of Mercury happens only 14 times in the 21st century (2001 to 2100).

Transits of Mercury always occur in either May or November.

The last four were in 1999 (November 15), 2003 (May 7), 2006 (November 8) and 2016 (May 9); the next will be on November 11, 2019, and the next after that will be November 13, 2032.

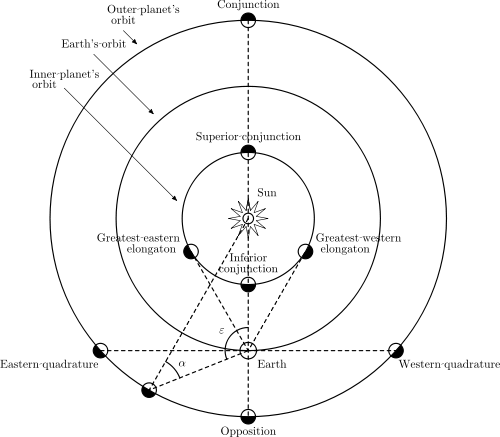

What causes a transit of Mercury? Only planets that orbit the sun inside of Earth’s orbit – Mercury and Venus – ever transit the sun, as seen from Earth. If Mercury orbited the sun on the same plane that Earth does, there would be three to four transits of Mercury each calendar year.

However, Mercury’s orbital plane in inclined at 7 degrees to the ecliptic (Earth’s orbital plane). That means when Mercury swings between the Earth and sun at inferior conjunction (see illustration below) every four or so months, Mercury usually sweeps to the north or south of the solar disk. Therefore a transit of Mercury is fairly rare, only happening 13 to 14 times per century.

Each time Mercury circles the sun in its short and swift orbit of 88 Earth-days, Mercury travels north of the ecliptic (Earth’s orbital plane) for about half its orbit, and south of the ecliptic during the other half of its orbit. Twice in its orbit, Mercury crosses the Earth’s orbital plane at points called nodes. When Mercury is traveling from north to south, it’s called a descending node; and when Mercury is traveling south to north, it’s called an ascending node.

Whenever Mercury crosses a node in close vicinity to reaching inferior conjunction, a transit of Mercury is not only possible but inevitable. Mercury crosses its ascending node almost concurrently with the inferior conjunction on November 11, 2019, to present a rather rare transit of Mercury.

Descending node transits can only happen during the first half of May, and ascending node transits in the first half of November. At other times of the year, Mercury at inferior conjunction would either pass north or south of the sun’s disk.

Dates for transits of Mercury in the 21st century (2001 to 2100). All Mercury transits happen in either May (descending node) or November (ascending node).

May 7, 2003

Nov 8, 2006

May 9, 2016

Nov 11, 2019

Nov 13, 2032

Nov 7, 2039

May 7, 2049

Nov 9, 2052

May 10, 2062

Nov 11, 2065

Nov 14, 2078

Nov 7, 2085

May 8, 2095

Nov 10, 2098

November (ascending node) transits happen about twice as often as May (descending node) transits. This is because Mercury has a very eccentric (oblong) orbit whereby Mercury comes a whopping 24 million kilometers (15 million miles) closer to the sun at perihelion (closest point to the sun in its orbit) than at aphelion (farthest point). In May, Mercury is rather close to aphelion, and quite far from the sun, which severely narrows the window of opportunity for a May transit. In November, Mercury swings rather near perihelion, and quite close to the sun, widening the period of time during which a November transit is possible.

Mercury transit cycles. Note that after a May transit, a November transit faithfully comes 3 1/2 years later (for instance: May 9, 2016 and November 11, 2019). Transits recur on nearly the same date in cycles of 46 years (for instance: May 9, 2016 and May 10, 2062). November transits, which are more common than May transits, occasionally recur in periods of seven years, and more frequently in periods of 13 and 33 years.

May transits, which are less common than November transits, frequently recur in periods of 13 and/or 33 years. The 46-year cycle represents a combination of 13 and 33 years (13 + 33 = 46).

By the way, this time around – November 11, 2019 – Mercury comes the closest to the sun’s center since the Mercury transit of November 10, 1973. Mercury won’t get closer to sun’s center again until November 12, 2190. Note that there are 46 years between 1973 and 2019, and 217 years between 1973 and 2190. This especially good 217-year periodicity is made up of four 46-year periods and one 33-year period.

Seven century catalog of Mercury transits: 1601 A.D. to 2300 A.D.

Bottom line: Our solar system’s innermost planet, Mercury, passes directly in front of the sun on November 11, 2019. Who will see it, how to watch, equipment needed, transit times.