Landscapes can change over time—sometimes drastically—even so, it is difficult to imagine that someplace as dry as the Sahara once contained verdant river basins with flowing water, but that indeed appears to be the case. In a new study published in the journal Nature Communications on November 10, 2015, scientists present strong evidence that the now desert was once the site of an extensive network of rivers that emptied into the Atlantic Ocean.

Early hints of the paleoriver network were discovered years ago in the deep submarine Cape Timiris Canyon, which lies off the coast of Mauritania in Africa. Specifically, scientists discovered fine sediments that appeared to have originated from ancient rivers. They suspected that the nearby western Sahara was once a much wetter environment and dubbed it the “green” Sahara. Humid episodes were common in this region tens to hundreds of thousands of years ago because of changes in the amount of the Sun’s energy reaching the Earth and associated changes in monsoon rains.

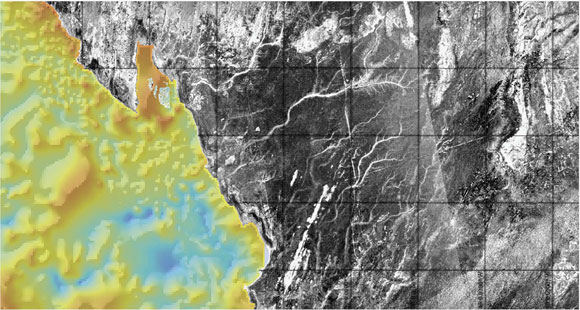

These older findings piqued the interest of a team of European and African scientists, who went on a virtual hunt for the ancient river network with newly acquired satellite data. The ground-penetrating radar images of the region that they compiled indeed show evidence of an ancient complex river network underneath the thick layers of sand. Below is key image from their new study.

Russell Wynn, a scientist affiliated with the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton who was involved in earlier studies of the offshore submarine canyon but not in the present research, told the Guardian newspaper:

It’s a great geological detective story and it confirms more directly what we had expected. This is more compelling evidence that in the past there was a very big river system feeding into this canyon.

The newly discovered river system was likely part of the enormous Tamanrasett River valley, which is no longer in existence, but at one time, it’s drainage basin was larger than that of the present day Ganges–Brahmaputra River basin in Asia and the St. Lawrence River basin in North America.

The region where the paleoriver network was discovered is now a part of the Sahara, the largest hot desert on Earth.

Satellite data for the new study were obtained from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

Charlotte Skonieczny, lead author of the new study, is a scientist affiliated with the French Research Institute for Exploitation of the Sea (IFREMER) and the University of Lille Nord de France. Co-authors of the study included P. Paillou, A. Bory, G. Bayon, L. Biscara, X. Crosta, F. Eynaud, B. Malaize, M. Revel, N. Aleman, J.-P. Barusseau, R. Vernet, S. Lopez, and F. Grousset. The research was funded in part by the French National Centre for Scientific Research.

Enjoying EarthSky? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Bottom line: Scientists have captured amazing new radar images of a paleoriver network underneath the desert sands of the western Sahara region. Their work was published in the journal Nature Communications on November 10, 2015.

Blossoming Atacama desert in Chile

U.S. deserts wet until 8,200 years ago

On desert Mars, vastly more interior water than previously thought