What is it? The March equinox – aka the vernal equinox – marks the sun’s crossing above Earth’s equator, moving from south to north. Earth’s tilt on its axis is what causes this northward shift of the sun’s path across our sky at this time of year. Earth’s tilt is now bringing spring and summer to the Northern Hemisphere. At the same time, the March equinox marks the beginning of autumn – and a shift toward winter – in the Southern Hemisphere.

When is it? The sun crosses the celestial equator – a line directly above Earth’s equator – at 9:02 UTC on March 20, 2025 (4:02 p.m. CDT).

No matter where you are on Earth, the equinox brings us a number of seasonal effects, noticeable to nature lovers around the globe.

Join us in making sure everyone has access to the wonders of astronomy. Donate now!

Equal day and night on the equinox?

At the equinox, Earth’s two hemispheres are receiving the sun’s rays equally. Night and day are often said to be equal in length. In fact, the word equinox comes from the Latin aequus (equal) and nox (night). For our ancestors, whose timekeeping was less precise than ours, day and night likely did seem equal. But today we know it’s not exactly so.

Read more: Are day and night equal at the equinox?

Fastest sunsets at the equinoxes

The fastest sunsets and sunrises of the year happen at the equinoxes. We’re talking here about the length of time it takes for the whole sun to sink below the horizon.

Read more: Fastest sunsets happen near equinoxes

Sun rises due east and sets due west?

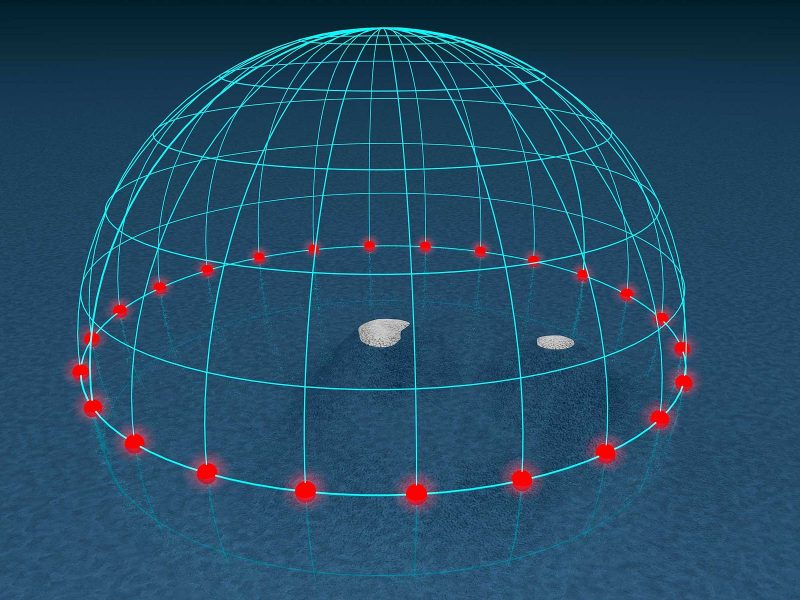

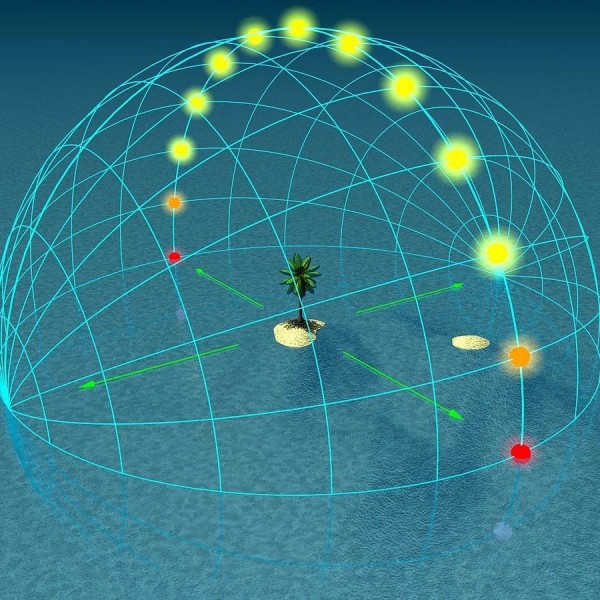

Here’s another equinox phenomenon. You might hear that the sun rises due east and sets due west at the equinox. Is that true? Yes it is. In fact, it’s the case no matter where you live on Earth, with the exception of the North and South Poles. At the equinoxes, the sun appears overhead at noon as seen from Earth’s equator, as the illustration below shows. This illustration shows the sun’s location on the celestial equator, every hour, on the day of the equinox.

No matter where you are on Earth – except at the Earth’s North and South Poles – you have a due east and due west point on your horizon. That point marks the intersection of your horizon with the celestial equator: the imaginary line above the true equator of the Earth.

The sun is on the celestial equator, and the celestial equator intersects all of our horizons at points due east and due west. Voila! The sun rises due east and sets due west.

Read more: Sun rises due east and sets due west

More March equinox effects

And there are also plenty more effects in play around the time of the March equinox that all of us can notice. In the Northern Hemisphere, the March equinox brings earlier sunrises, later sunsets and sprouting plants.

Meanwhile, you’ll find the opposite season – later sunrises, earlier sunsets, chillier winds, dry and falling leaves – south of the equator.

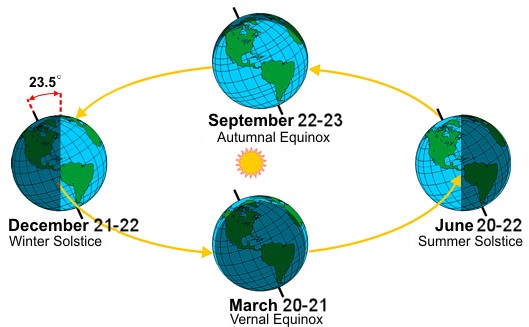

The equinoxes and solstices are caused by Earth’s tilt on its axis and ceaseless motion in orbit. You can think of an equinox as happening on the imaginary dome of our sky, or as an event that happens in Earth’s orbit around the sun.

The Earth-centered view

If you think of it from an Earth-centered perspective, you can think of the celestial equator as a great circle dividing Earth’s sky into its Northern and Southern Hemispheres. The celestial equator is an imaginary line wrapping the sky directly above Earth’s equator. At the equinox, the sun crosses the celestial equator to enter the sky’s Northern Hemisphere.

The Earth-in-space view

If you think of it from an Earth-in-space perspective, you have to think of Earth in orbit around the sun. And we all know Earth doesn’t orbit upright but is instead tilted on its axis by 23 1/2 degrees. So Earth’s Northern and Southern Hemispheres trade places in receiving the sun’s light and warmth most directly. We have an equinox twice a year – spring and fall – when the tilt of the Earth’s axis and Earth’s orbit around the sun combine in such a way that the axis is inclined neither away from nor toward the sun.

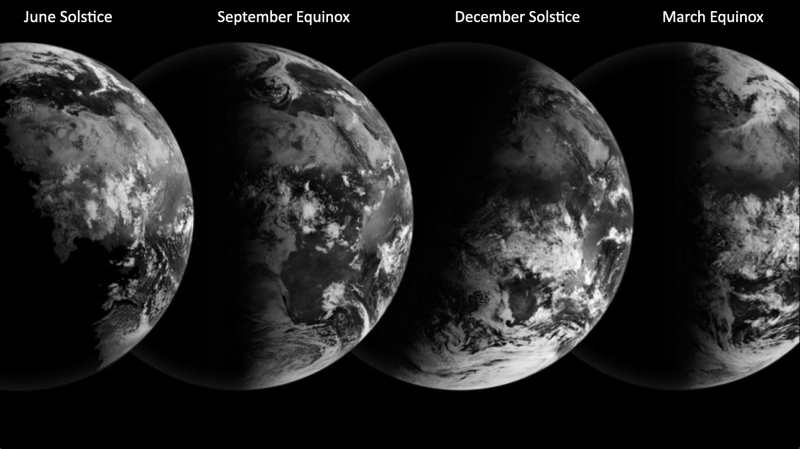

Here are satellite views of Earth on the solstices and equinoxes, via NASA Earth Observatory.

Things change fast around the equinoxes

Since Earth never stops moving around the sun, the position of the sunrise and sunset – and the days of approximately equal sunlight and night – will change quickly.

The video below was the Astronomy Picture of the Day for March 19, 2014. APOD explained:

At an equinox, the Earth’s terminator – the dividing line between day and night – becomes vertical and connects the North and South Poles. The time-lapse video [below] demonstrates this by displaying an entire year on planet Earth in 12 seconds. From geosynchronous orbit, the Meteosat satellite recorded these infrared images of the Earth every day at the same local time. The video started at the September 2010 equinox with the terminator line being vertical.

As the Earth revolved around the sun, the terminator was seen to tilt in a way that provides less daily sunlight to the Northern Hemisphere, causing winter in the north. As the year progressed, the March 2011 equinox arrived halfway through the video, followed by the terminator tilting the other way, causing winter in the Southern Hemisphere and summer in the north. The captured year ends again with the September equinox, concluding another of billions of trips the Earth has taken – and will take – around the sun.

Where are signs of the March equinox in nature?

Everywhere! Forget about the weather for a moment, and think only about daylight. In terms of daylight, the knowledge that spring is here – and summer is coming – permeates all of nature on the northern half of Earth’s globe.

Notice the arc of the sun across the sky each day. You’ll find that it’s shifting toward the north. Responding to the change in daylight, birds and butterflies are migrating back northward, too, along with the path of the sun.

The longer days do bring with them warmer weather. People are leaving their winter coats at home. Trees are budding, and plants are beginning a new cycle of growth. In many places, spring flowers are beginning to bloom.

Meanwhile, in the Southern Hemisphere, the days are getting shorter and nights longer. A chill is in the air. Fall is here, and winter is coming!

Bottom line: Happy equinox! The 2024 March equinox falls March 20 at 3:06 UTC. So many parts of the world will see the equinox arrive on March 19. All you need to know here.