Webb’s 1st Mars images

The Hubble telescope sees at visible (or ultraviolet) wavelengths. But the new Webb telescope sees mostly in the infrared. It picks up a part of the electromagnetic spectrum we humans can’t see with our eyes, but that we can sense as heat. And now we have the first infrared images and spectra from Mars, released today (September 19, 2022) in the Webb Telescope blog. Alise Fisher, who wrote about the images for NASA, said they complement:

… Data being collected by orbiters, rovers, and other telescopes.

And, wow, do they ever! To me, it feels as though we’re literally seeing Mars with new eyes.

What do we see?

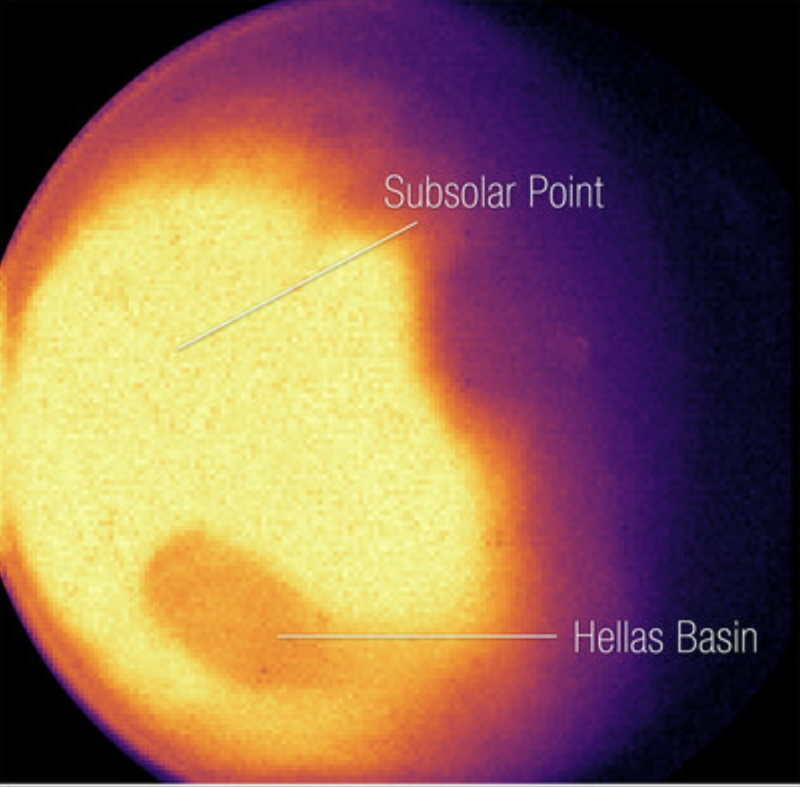

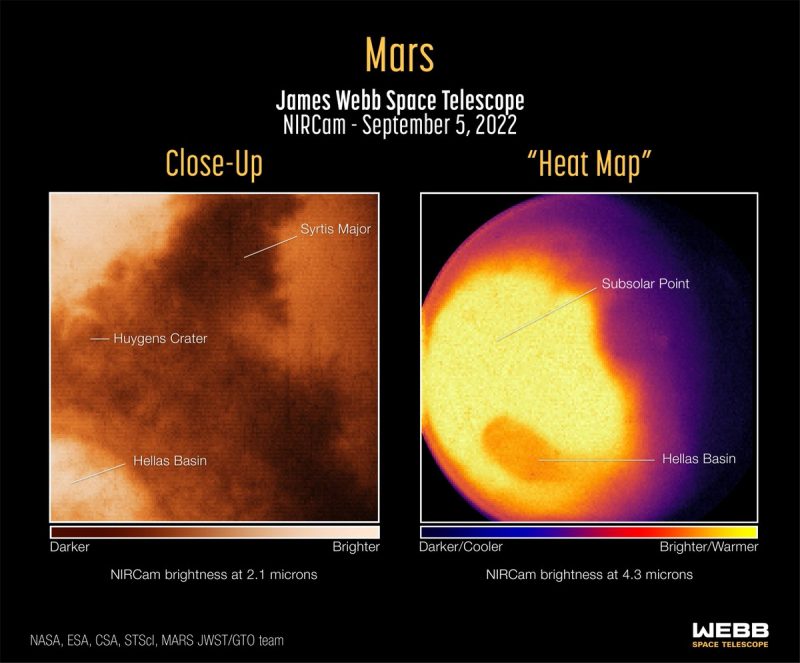

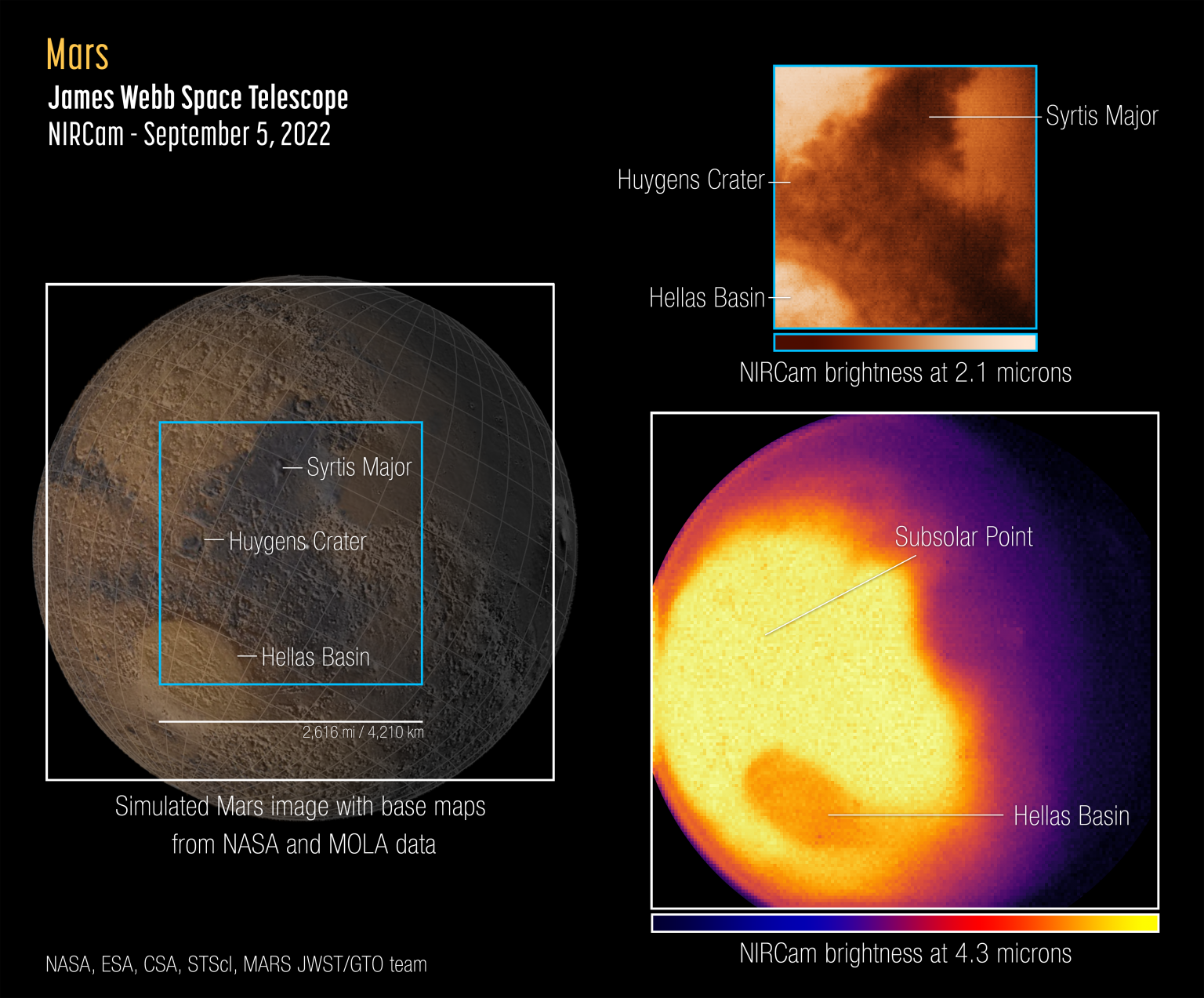

Notice the words “subsolar point” on the Mars images on this page. That’s the point on Mars where where the sun is at the zenith (directly overhead). And, of course, Mars is spinning. It spins on its axis at nearly the same rate as Earth (Mars completes one revolution every 24.6 hours, so its day is nearly the same length as our day). Mars is spinning beneath that subsolar point, and what we’re seeing in that image is the heat pouring from the brightest part of Mars’ dayside (in contrast to its cooler nightside).

What can we learn? Writing at the Webb Telescope blog, Alise Fisher noted that Webb:

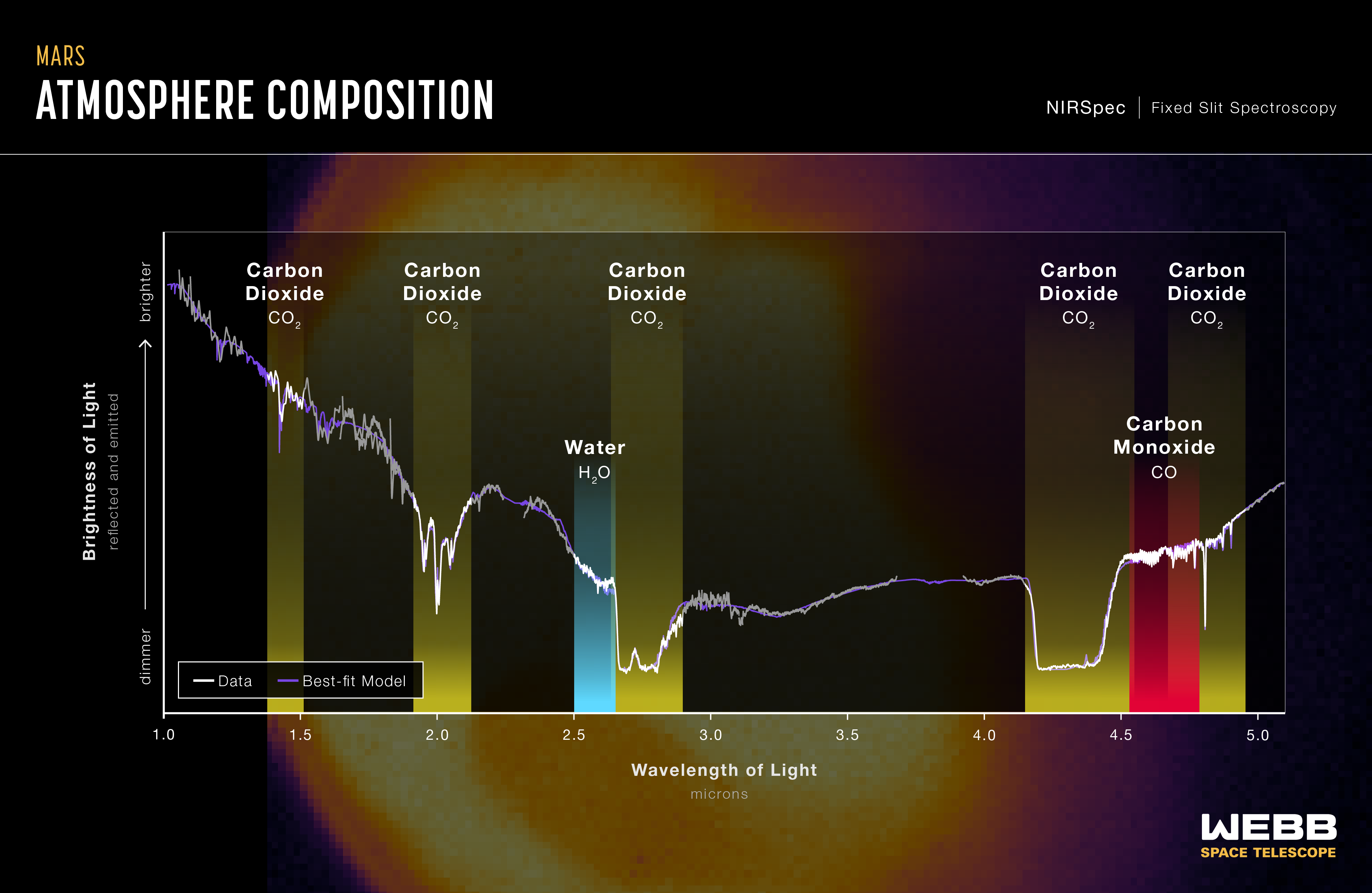

… Provides a view of Mars’ observable disk (the portion of the sunlit side that is facing the telescope). As a result, Webb can capture images and spectra with the spectral resolution needed to study short-term phenomena like dust storms, weather patterns, seasonal changes, and, in a single observation, processes that occur at different times (daytime, sunset, and nighttime) of a Martian day.

And NASA said:

The brightness decreases toward the polar regions, which receive less sunlight, and less light is emitted from the cooler northern hemisphere, which is experiencing winter at this time of year.

These fascinating new Webb observations make me think about some of the great Mars observers of the past – like Christiaan Huygens in the 1600s and Percival Lowell in the early 20th century – peering at Mars through their earthbound telescopes. I wish they could have seen these Webb images!

It’s a waxing gibbous Mars

By the way, also notice that Mars isn’t quite full in the image above. Webb’s observation outpost in space is nearly a million miles (1.6 milion km) away at the sun-Earth Lagrange point 2 (L2). It’s four times the moon’s distance away from us. That’s in contrast to Mars’ distance from Earth in September 2022 of about 79 million miles (about 127 million km), according to TheSkyLive.com). So, essentially, Earth and the telescope are the same distance away from Mars.

And, right now, Mars appears nearly full from the vantage point of Webb (or Earth). Nearly, but not quite. That’s because Earth is currently racing up behind Mars in its smaller, faster orbit. And we’ll pass between Mars and the sun on December 8, 2022. That’s when its day side will be facing us fully. And it’s why now is a great time to begin watching Mars, with the eye alone.

But Mars’ relative nearness to Earth now and brightness in our sky isn’t helpful to those trying to observe Mars with Webb. As explained by Alise Fisher at the Webb Telescope blog:

Because it is so close, the red planet is one of the brightest objects in the night sky in terms of both visible light (which human eyes can see) and the infrared light that Webb is designed to detect. This poses special challenges to the observatory, which was built to detect the extremely faint light of the most distant galaxies in the universe. Webb’s instruments are so sensitive that without special observing techniques, the bright infrared light from Mars is blinding, causing a phenomenon known as ‘detector saturation.’ Astronomers adjusted for Mars’ extreme brightness by using very short exposures, measuring only some of the light that hit the detectors, and applying special data analysis techniques.

There’s so much more to say about these images. There’s lots more detail about at Alise Fisher’s post at the Webb Space Telescope blog. Enjoy the images! No doubt there are more to come …

Bottom line: Webb’s first Mars images and spectra were released today (September 19, 2022).