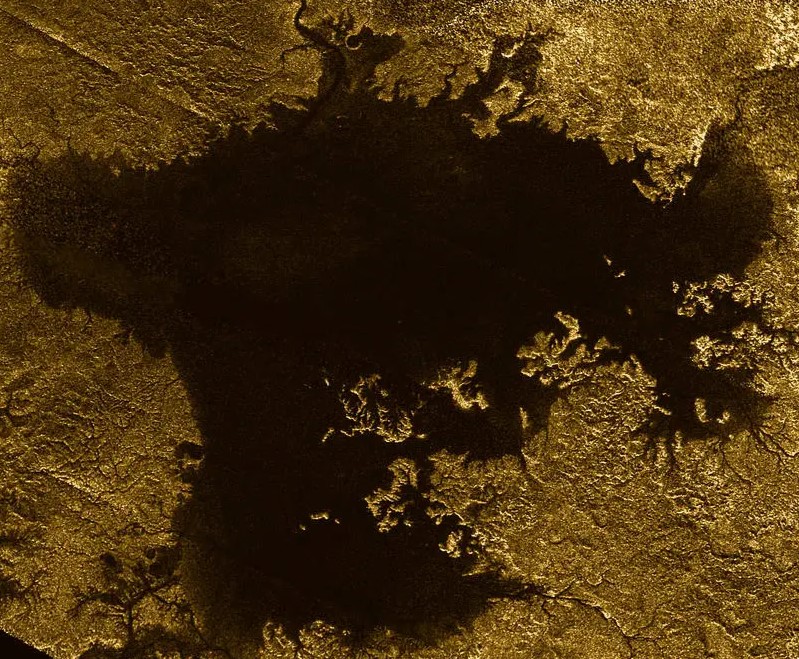

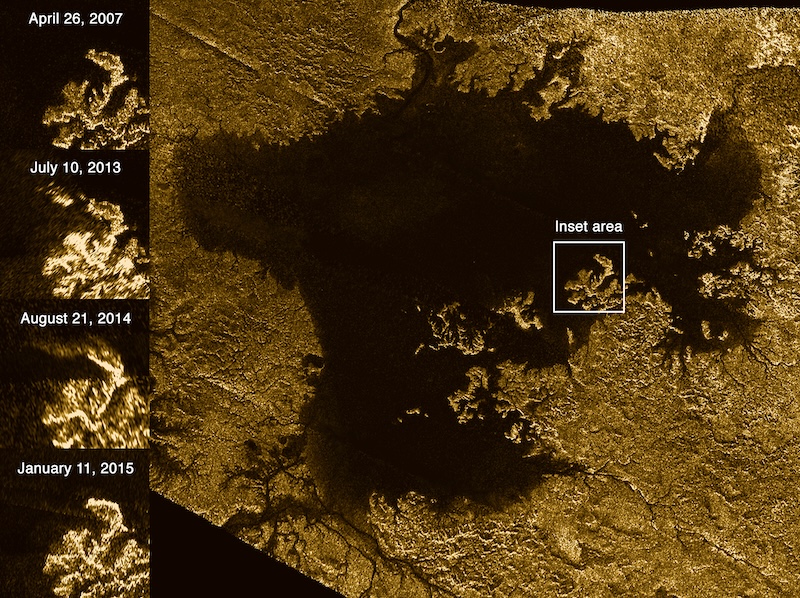

In radar images from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, the lakes and seas on the surface of Saturn’s large moon Titan do resemble bodies of water on Earth. But in Titan’s extreme cold (-290 degrees Fahrenheit or -179 degrees Celsius), the seas consist of hydrocarbons, liquid methane and ethane. The Cassini mission also spotted bright areas – like islands – that appeared to be floating on the seas and then disappearing. Scientists dubbed them Titan’s magic islands. On January 4, 2024, a team of U.S. researchers said the islands are likely floating chunks of porous (honeycombed), frozen organic solids.

The researchers published their peer-reviewed results in Geophysical Research Letters (AGU) on January 4, 2024.

The 2024 lunar calendars are here! Best New Year’s gifts in the universe! Check ’em out here.

How do Titan’s ‘magic islands’ form?

Cassini, which ended its mission in 2017, noticed the new features in the sea appear in 2013. They seemed ephemeral, lasting anywhere from hours to a few weeks before disappearing. Scientists came up with various theories to explain them. Were they actual islands made of solid material? Or might they be a phantom phenomenon caused by waves? If real, researchers theorized they could be suspended solids, floating solids or bubbles of nitrogen gas. If they were solids, then they must evaporate or dissolve over time.

Whatever they were, they seemed to be unique to Titan.

Floating organics?

Xinting Yu is a planetary scientist at the University of Texas San Antonio and lead author of the new study. She wondered if the islands could be composed of organic material. She stated:

I wanted to investigate whether the magic islands could actually be organics floating on the surface, like pumice that can float on water here on Earth before finally sinking.

The idea wasn’t implausible, since Titan is covered in organic material. Its atmosphere is filled with hydrocarbon “smog” and it snows organic molecules (as well as methane rains).

Float or sink?

The organic molecules in Titan’s atmosphere clump together and fall to the surface, reminiscent of snow on Earth. What would happen when those clumps landed on a lake or sea? Would they float or sink? The researchers said they could indeed float, but only if they are porous. The paper said:

We find that most molecules would land as solids. We also looked at what happens when these solids land on Titan’s hydrocarbon lakes. Imagine a sponge, full of holes; if the solids are like this, with 25%–60% of their volume being empty space, they can float.

The research team also wanted to know if the clumps would simply dissolve in the liquid. They came to the conclusion that they wouldn’t, since the lakes and seas are already saturated with other organic particles. The clumps of organic snow would simply float, although not for greatly extended periods of time. Yu said:

For us to see the magic islands, they can’t just float for a second and then sink. They have to float for some time, but not for forever, either.

Titan’s ‘magic islands’ must be porous

There’s a catch, though. Just like water, Titan’s liquids have surface tension. But it is weak, meaning that it is hard for solid material, even organics, to float. In fact, the study found that most of the frozen solids would be too dense to float. But how then do the islands form? They must be porous, like a honeycomb kind of structure or Swiss cheese. The clumps would need to be large enough and have the right ratio of holes and hollow tubes in them.

But it would work. In that scenario, the liquid methane and ethane would seep into the material slowly. As a result, the islands could stay suspended in the liquid and linger around long enough for Cassini to see them.

Also, single clumps likely couldn’t float, not for long anyway. But if they coalesced together to become larger, along the shorelines, then they could indeed float. The islands themselves may form in a process similar to calving on Earth, where pieces of glaciers break off and float away. On Titan, those separated chunks become the magic islands.

Smoothness of Titan’s seas and lakes

In addition, the findings help to explain another Titan mystery. Why are its lakes and seas so smooth, with little or no waves? If there is also a thin layer of the organic solids on top of the liquid, that frozen coating could explain why the lakes and seas look so smooth in radar images. As the paper explained:

Among all the hypotheses that have been proposed to explain the smoothness of the lakes and the observed radar-bright transient features on Titan, two hypotheses can explain both observations simultaneously: the absence/presence of waves or floating solids. The lack of wind-generated waves might account for the general smoothness of the lakes, while occasional waves could give rise to transient radar-right “magic island” phenomena. Likewise, a uniformly thin layer of floating solids could also explain the overall smoothness, with large clusters of floating solids potentially visible as “magic islands.”

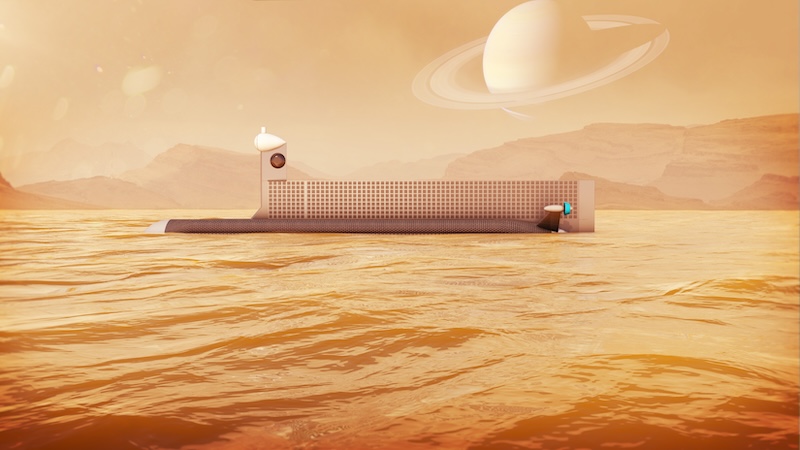

Titan’s lakes and seas will be exciting targets of exploration in the future. NASA’s Dragonfly, a car-sized rotorcraft drone, will be able to take a closer look as it travels to various locations on the frigid moon. Will it see any magic islands? Dragonfly is now scheduled to launch in 2028.

Bottom line: How do Titan’s ‘magic islands’ form in its hydrocarbon seas? A new study says they are likely porous, similar to a honeycomb, and composed of organic material.

Source: The Fate of Simple Organics on Titan’s Surface: A Theoretical Perspective

Read more: Ancient lake on Titan could have lasted thousands of years

Read more: Scientists find new surprises about Titan’s lakes