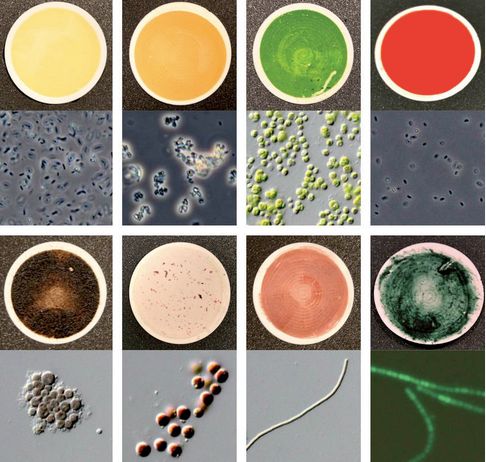

Any planets beyond our solar system – known as exoplanets – are incredibly far away. We barely glimpse them using modern technologies and have little hope of traveling within the timescale of a human lifespan to even the next-nearest known planet (which happens to belong to the Alpha Centauri system, just next door). That’s why astronomers and biologists have now systematically measured and catalogued the chemical fingerprints of 137 different species of microorganisms. These scientists say they want this work to enable future astronomers look from afar and recognize life on exoplanet surfaces. These results are available online, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on March 16, 2015.

Siddharth Hegde at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany led the research. In an interview with MPIA, he said:

Single-celled microorganisms dominate the history of life on Earth: they have been residents of Earth’s surface for at least 3.5 billion years … whereas plants have only been around for the past 460 million years.

Furthermore, they represent the extremes of the diversity of life. Microorganisms called extremophiles, literally ‘lovers of extreme environments,’ have time and time again surprised biologists with their hardiness. They can be found in some of the most extreme physical and geochemical environments on Earth, from hot springs in Yellowstone National Park to Antarctica to the interior of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor.

Since biologists believe that there are limits to the forms life can take (for example, all life on Earth requires liquid water) collecting biosignatures from extremophiles enabled the team to account for a wide range of possibilities for physical and geochemical conditions on exoplanets, and accordingly a wide range of possibilities for what the dominant form of life on a particular planet could be.

Enjoying EarthSky so far? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

For now, Hegde said, the 137 biosignatures make up “the most complete and diverse biosignature catalog to date.”

He said some of the microorganisms hail from the most extreme environments on Earth and that, taken together, the samples should allow for a cautious estimate of the diversity of biological colors on planets other than Earth.

Read more from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy

Bottom line: Scientists have now measured chemical fingerprints for 137 different species of microorganisms, with the goal of enabling future astronomers to recognize life on planets outside our solar system.