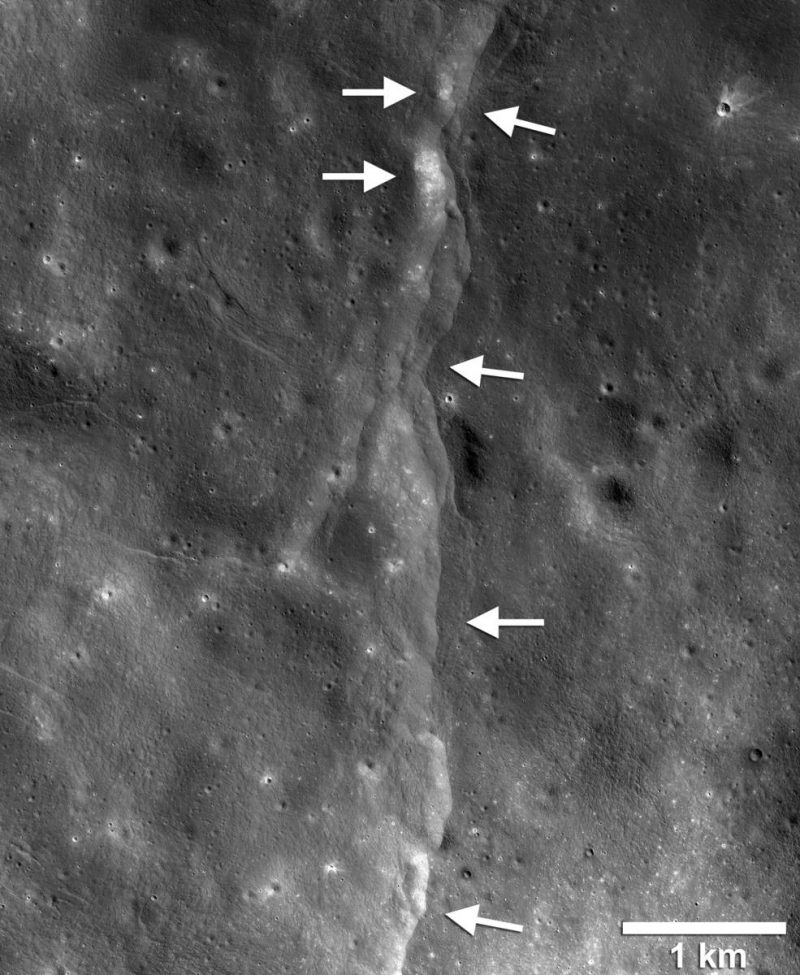

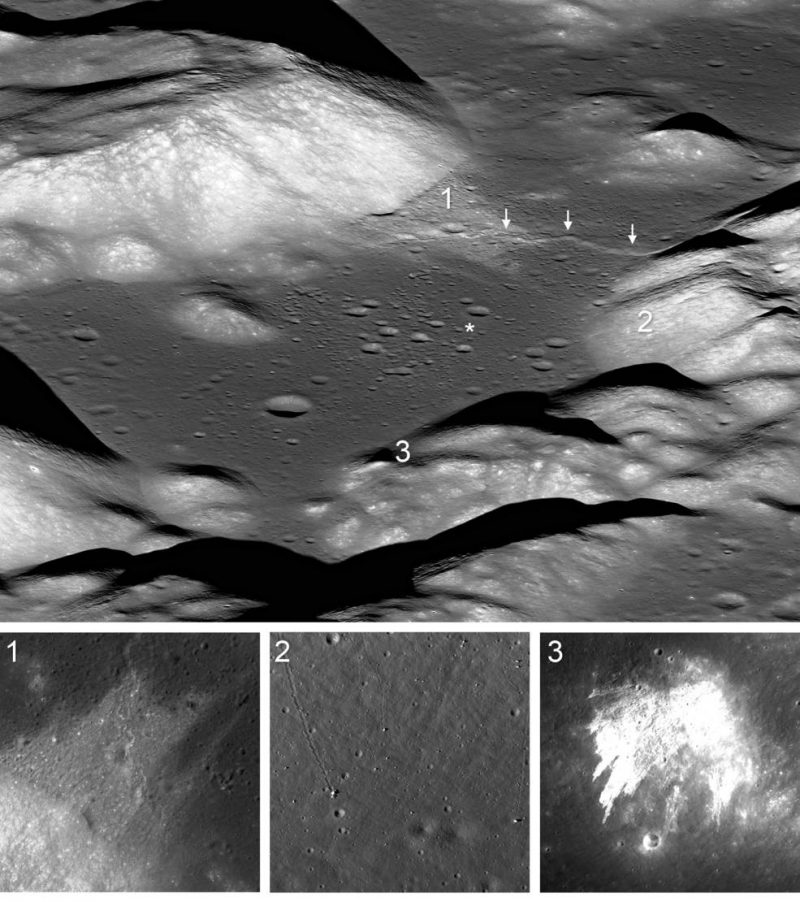

Visualization of Lee Lincoln scarp, a low ridge about 260 feet (80 meters) high and running north-south through the western end of the moon’s Taurus-Littrow valley, the site of the Apollo 17 moon landing. The scarp marks the location of a relatively young, low-angle thrust fault, a place where one section of crust is pushed up over a neighboring part. The land west of the fault was forced up and over the eastern side as the lunar crust contracted. Via NASA/Goddard/SVS/Ernie Wright, created from Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter photographs and elevation mapping.

The moon is shrinking as its interior cools, and a new study suggests that the change is triggering moonquakes.

NASA scientists said on May 13, 2019, that the moon has gotten more than about 150 feet (50 meters) smaller over the last several hundred million years. They compared the moon’s outer crust to a grape that “wrinkles as it shrinks down to a raisin,” and said the moon, too, wrinkles as it shrinks. Unlike the flexible skin on a grape, the moon’s surface crust is brittle, so it breaks as the moon shrinks, forming thrust faults, where one section of crust is pushed up over a neighboring part.

Thomas Watters is senior scientist in the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. He’s lead author of the study, which was published May 13 in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Geoscience. He said in a statement:

Our analysis gives the first evidence that these faults are still active and likely producing moonquakes today as the moon continues to gradually cool and shrink. Some of these quakes can be fairly strong, around five on the Richter scale.

The Apollo astronauts brought several seismometers to the lunar surface which recorded thousands of moonquakes between 1969 and 1977. For the study, scientists took a new look at the data from the seismometers, using a special algorithm, or mathematical program, developed to pinpoint quake locations.

The algorithm gave the scientists a better estimate of where the moonquakes happened. Using the revised location estimates from the new algorithm, the team found that eight of the 28 shallow quakes were within 18.6 miles (30 km) of faults visible in lunar images. This is close enough to tentatively attribute the quakes to the faults, said the researchers.

Watters said:

We think it’s very likely that these eight quakes were produced by faults slipping as stress built up when the lunar crust was compressed by global contraction and tidal forces, indicating that the Apollo seismometers recorded the shrinking moon and the moon is still tectonically active.

Read more about the researchers’ evidence here.

Renee Weber is a planetary seismologist at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, and study co-author. She said:

Establishing a new network of seismometers on the lunar surface should be a priority for human exploration of the moon, both to learn more about the moon’s interior and to determine how much of a hazard moonquakes present.

Here’s more from NASA:

The moon isn’t the only world in our solar system experiencing some shrinkage with age. Mercury has enormous thrust faults – up to about 600 miles (1,000 km) long and over a mile (3 km) high – that are significantly larger relative to its size than those on the moon, indicating it shrank much more than the moon. Since rocky worlds expand when they heat up and contract as they cool, Mercury’s large faults reveal that is was likely hot enough to be completely molten after its formation. Scientists trying to reconstruct the moon’s origin wonder whether the same happened to the moon, or if instead it was only partially molten, perhaps with a magma ocean over a more slowly heating deep interior. The relatively small size of the moon’s fault scarps is in line with the more subtle contraction expected from a partially molten scenario.

Bottom line: The moon is shrinking as its interior cools. A new study says that the shrinking is forming “thrust faults” that generate moonquakes.

Source: Shallow seismic activity and young thrust faults on the moon