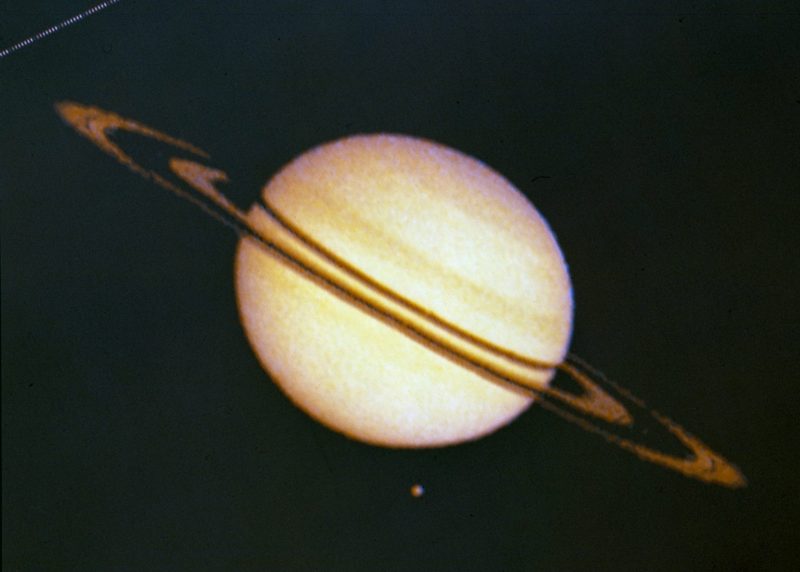

Pioneer 11 was the first earthly craft ever to fly past the planet Saturn. Its closest approach to the ringed planet was on September 1, 1979. And Patty Winter was at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California – where the Pioneer project was managed – watching the Saturn watchers on that historic day. In the story below, Patty shares her memories. Here’s Watching the Saturn Watchers, by Patty Winter …

The scientists at Pioneer Saturn Mission Control are glued to their computer screens like Las Vegas tourists in front of one-armed bandits. What they don’t want to see is a field of dollar signs: The computer’s ironic way of saying they’ve just lost a multimillion-dollar spacecraft. Pioneer 11 is about to dart past the rings of Saturn. Theoretically, it will pass well outside them. But no one on Earth knows quite how far out the rings extend. And at 70,000 miles an hour (112 km/hr), a piece of ice and rock no bigger than a snowball could destroy Pioneer.

In an alcove-cum-TV studio at one side of the room, NASA’s Larry King is describing the scene for a worldwide audience. It’s Saturn-day, September 1, 1979, a few minutes before nine in the morning. The expected ring-crossing time is 9:02 a.m. PDT. The scientists here at Ames are giving the event a two-minute leeway on either side. They won’t consider the crossing successful until 9:04 has passed safely.

Watching Pioneer 11

Over at the Space Sciences Building, nearly a hundred journalists are equally attentive to their screens. The TV monitors allow them to peek over the shoulders of the mission controllers and see the data streaming in from Pioneer. At 9:00, Pioneer’s normal output of letters and numbers is still on the screen. In reality, we’re awaiting an event that has already happened. Pioneer crossed Saturn’s ring plane at 7:36 a.m. PDT. But it’s taken almost an hour and a half for the bits of information to make their way through a billion miles (1.6 billion km) of emptiness to the waiting antenna in Spain.

Click here to see current distance and location of Pioneer 10 and 11

Awaiting Pioneer’s signal

Just after 9:01 now, and Larry King is counting down the seconds to the predicted crossing time. He reaches zero, and the usual data are still on the screen. But the scientists and press people remain silent.

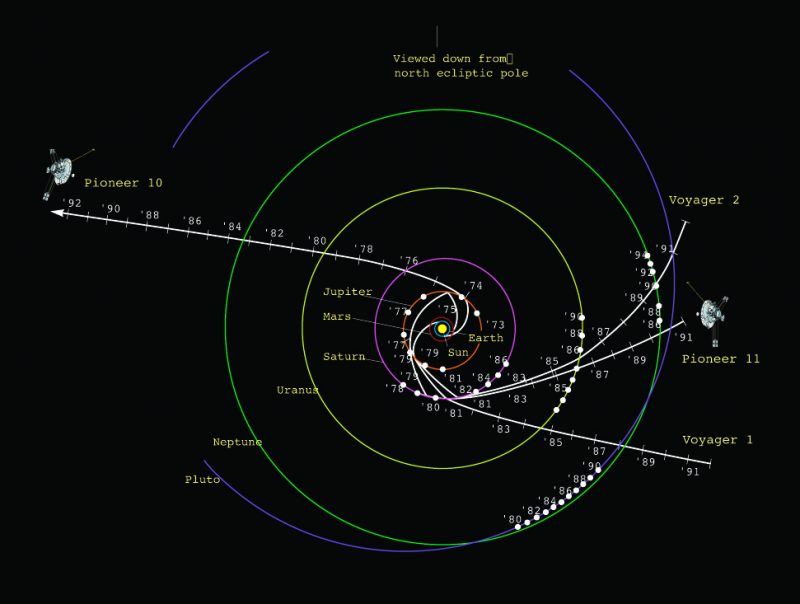

It’s impossible not to wish Pioneer well. Originally built only to explore Jupiter before tumbling its way to infinity, scientists redirected Pioneer 11 toward Saturn a few years later. It’s now giving us our first close-up look at the beautiful ringed planet before joining Pioneer 10 as one of the first artificial objects to leave our solar system.

The tiny Pioneers: only 9 by 9.5 feet (2.7 by 2.9 meters) big, alone in space except for radio contact with their small home planet, listening to instructions and beeping back their responses. Pioneer 10 is now out past the orbit of Uranus. In 1987, it will cross the hypothetical boundary of our solar system and continue toward the constellation Taurus. Pioneer 11 is going in almost the opposite direction.

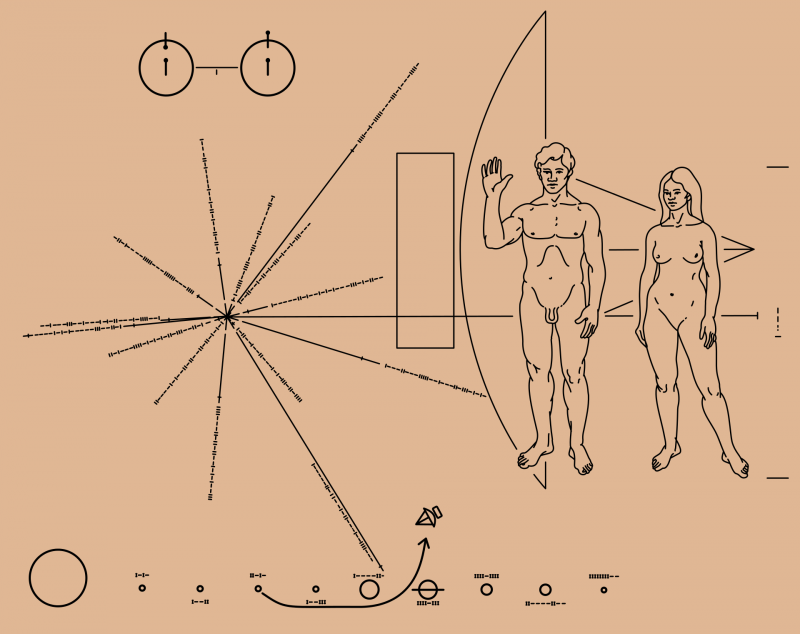

A message to the stars

Each of them carries a small gold plaque with a message from the people of the 3rd planet from Sol, just in case somebody out there finds one of the little travelers. It probably won’t happen, but it seems only polite to introduce ourselves, just in case.

Pioneer’s extended journey

But back to Saturn, and back to the blue-and-white planet across the sun from it. The screens at Ames are still giving out good news, but has Pioneer actually gone past the rings yet? We don’t know for certain, since we’re not exactly sure where the rings are. And there have been some problems receiving the data. The people who designed Pioneer 11 never expected it to have to send back data for all these years and across all these miles. And who knew that the sun would send out a violent electromagnetic storm just a few days before the Saturn encounter?

Amazingly, we can still hear Pioneer’s tiny transmitter through the hash, and the instruments are working beautifully. Charlie Hall and the Pioneer team have been happy to be getting anything, so they’re overjoyed at the wealth of data they’ve been receiving. They have data on Saturn’s magnetic field and radiation belts, on its atmosphere and on its mysterious moon Iapetus.

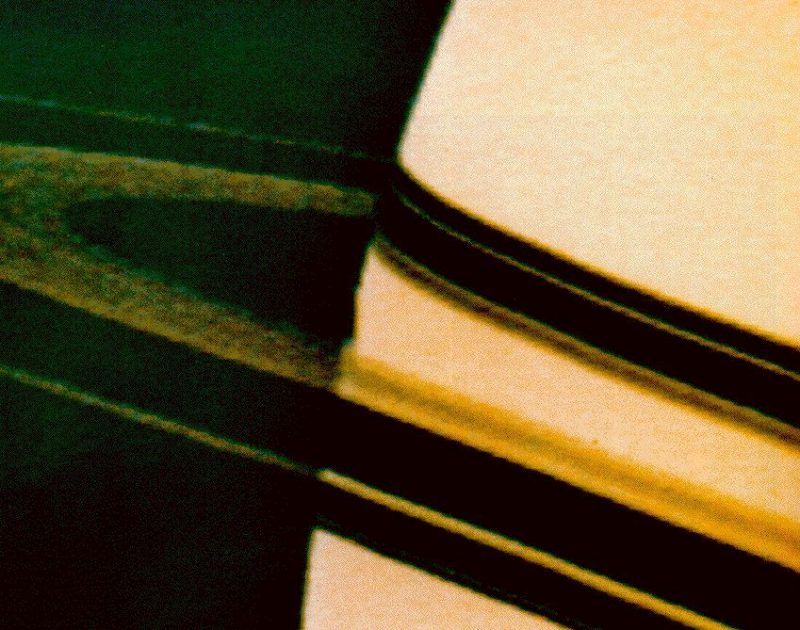

Images from deep space

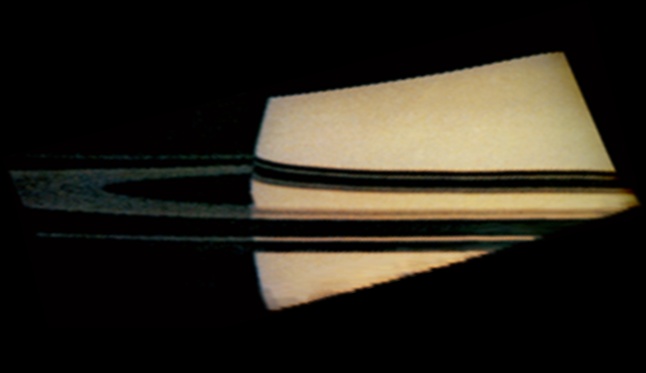

And the photographs! Black-and-white ones taken at various wavelengths to bring out different details of Saturn’s disk; color shots of the planet with the rings almost edge-on; and breathtaking color photos of the rings themselves: Those razor-thin rings, thousands of times as wide as they are thick, so ethereal and fragile looking. But it would take only one little pebble to cripple Pioneer.

Pioneer phones home

We’re coming up on 9:03, and there’s a growing feeling at Ames that it’s going to be all right. An accident could happen at any time, of course, but Saturn’s gravitational field has attracted virtually all nearby material into the constantly shifting bands around its middle, so the rest of the vicinity is almost empty, or so the scientists hope. Now Larry King is telling us it’s 9:04, and the computer screens haven’t changed. Still that same reassuring mixture of letters and numbers, and no dollar signs.

Someone in Mission Control says loudly:

We made it.

Applause and a few whoops fill the press room. It isn’t a wild reaction. It’s not like watching Apollo 17 blaze into the Florida night and inwardly chanting, Go! Go! Go! After all, we can’t actually see this milestone. Pioneer can only take still photographs. The human reaction this time is more a sigh of relief, a happy feeling that a small emissary from Earth has been given a warm welcome by a neighbor as it heads for the stars.

Bottom line: Patty Winter of Menlo Park, California, recalls the day that Pioneer 11 passed the rings of Saturn. The Pioneer mission was managed by NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, which today maintains the Pioneer mission’s historical archive.