Australian astronomers have now chimed in on the subject of why our Milky Way galaxy has fewer orbiting satellites than a prevailing theory of the universe – cold dark matter theory – says it should. They say the reason is that, according to their measurements, there’s only half the amount of dark matter in the Milky Way as previously thought, only 800 billion times the mass of our sun.

Their ideas are the latest in a series of widely varying researches, all attempting to explain the “missing” Milky Way satellites.

Australian astrophysicist Prajwal Kafle and his team used a method developed almost 100 years ago – before dark matter was a gleam in any astrophysicist’s eye – to measure dark matter. The famous British astronomer James Jeans devised the technique in 1915.

Dr. Kafle, who is originally from Nepal, says he and his team were able to measure the mass of the dark matter in the Milky Way by studying the speed of stars throughout the galaxy. He says they probed to the edges of the Milky Way for the first time, looking closely at the fringes of the galaxy some 5 million trillion kilometers from Earth. Kafle said:

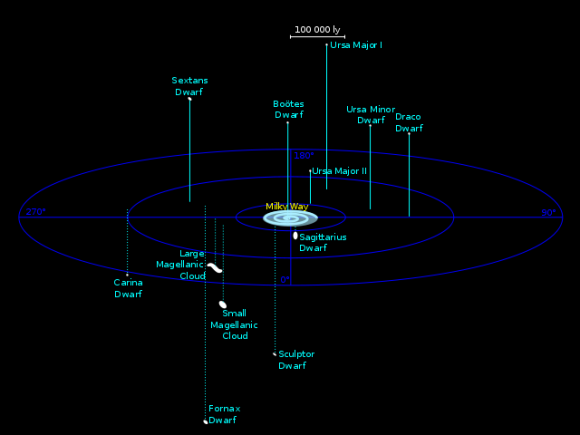

The current idea of galaxy formation and evolution, called the lambda cold dark matter theory, predicts that there should be a handful of big satellite galaxies around the Milky Way that are visible with the unaided eye, but we don’t see that.

When you use our measurement of the mass of the dark matter the theory predicts that there should only be three [large] satellite galaxies out there, which is exactly what we see; the Large Magellanic Cloud, the Small Magellanic Cloud and the Sagittarius Dwarf Galaxy.

However, other research programs have reached different conclusions to explain the shortage of large satellites galaxies for the Milky Way. About a month ago, European scientists – cosmologists and particle physicists, working together – said that dark matter particles might have interacted with photons and neutrinos in the young universe. If that scenario is correct, the dark matter would have “scattered,” and this scattering would have led to fewer Milky Way satellites, without relying on the decrease in mass for the Milky Way’s satellites suggested by the Australian astronomers.

And there have been other ideas. For example, in 2011, astronomers suggested that the Milky Way killed off its satellites shortly after the first stars appeared, about 150 million years after the Big Bang.

Astronomers nowadays generally agree that dark matter makes up some 25 percent of the mass of our universe. They agree that ordinary matter – all things made of ordinary atoms, like galaxies, stars, planets and human beings – makes up only 4% of the mass of the universe. The rest of the universe’s mass is dark energy, according to modern cosmological theories.

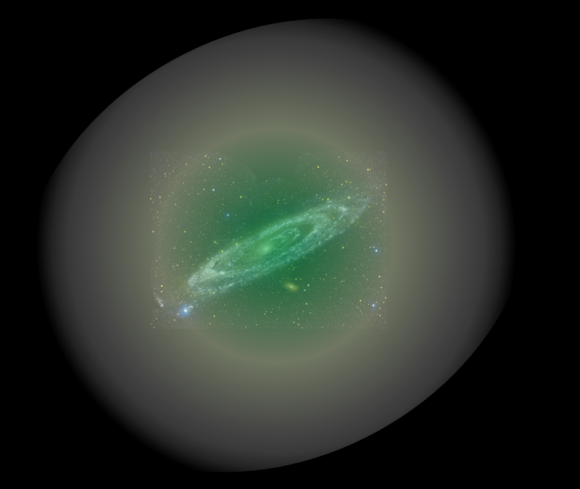

Dark matter is thought to surround us, but it doesn’t reflect light as ordinary matter does, and so it is invisible. Also, dark matter doesn’t interact with ordinary matter in ordinary ways; for example, if you hold up one thumb, astronomers say, millions of dark matter particles will flow through it every second. Thus dark matter has proven elusive to astronomers’ direct measurements. But dark matter does interact gravitationally. That’s what the Australian astronomers are measuring; they’re measuring the speeds of stars in our galaxy, which are determined by the overall mass of the galaxy, including its dark matter.

Do we need all three of the results mentioned above – dark matter particles interacting with photons and neutrinos, Milky Way killing off its satellites, dark matter being half what we thought – to explain the Milky Way’s missing satellites? Logically, one wouldn’t think so.

Will the Australian astronomers’ new measurements showing half the dark matter for the Milky Way be confirmed by other astronomers, and is it the answer to the missing satellite dilemma? That answer remains unclear for now, but it’s fascinating that astronomers have devised these different creative projects and ideas to explain the missing Milky Way satellite mystery.

Bottom line: Australian astronomers say our Milky Way galaxy has only half the dark matter we thought it did. If so, it explains the shortage of Milky Way satellites.