Could Mars have been the first planet in our solar system to support life? New research suggests it’s possible. Recently, EarthSky reported on a study showing that Mars was once likely a water world. It might have had oceans even before Earth did. On November 17, 2022, European researchers announced a study that reaches a similar conclusion. And the new study goes a bit further, suggesting that icy asteroids brought enough water to early Mars for a global ocean at least 980 feet (300 meters) deep (or deeper in some places). If so, those same asteroids might have brought organic molecules needed for life to begin on a young Mars.

The researchers – at the Center for Star and Planet Formation (StarPlan) at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark and other institutions in Europe – published their peer-reviewed findings in Science Advances on November 16, 2022.

The study also includes researchers from the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris (IPGP) at the University of Paris, the Institute of Geochemistry and Petrology (GeoPetro) at ETH Zürich and the University of Bern Physics Institute.

Asteroids bring water and organics to Mars

Just as with Earth, asteroids bombarded early Mars. Scientists said that these asteroids transported water and organic molecules throughout the solar system. Indeed, such asteroids may have played a vital role in the emergence of life on Earth. The new study said (and re-confirmed) that these asteroids brought water to Mars, as well. They also carried organic molecules, such as amino acids, necessary for life as we know it. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins. Martin Bizzarro from the Center for Star and Planet Formation (StarPlan) at the University of Copenhagen said:

At this time, Mars was bombarded with asteroids filled with ice. It happened in the first 100 million years of the planet’s evolution. Another interesting angle is that the asteroids also carried organic molecules that are biologically important for life.

Enough water for a deep global ocean

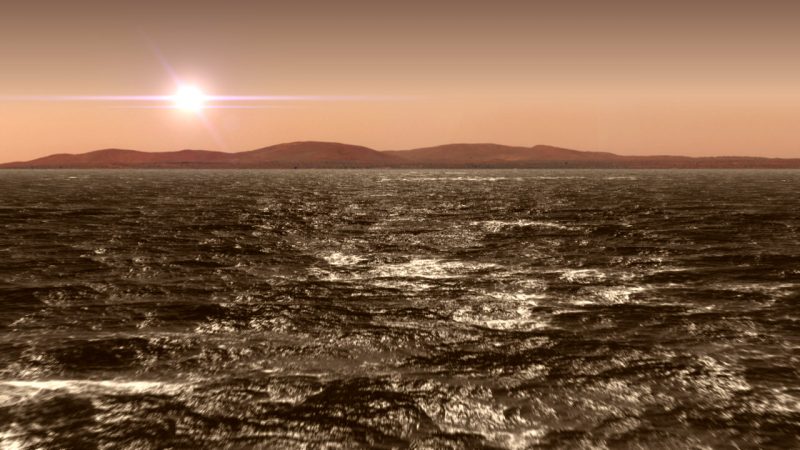

We know that Mars once had much more water than it does today. Lakes and rivers crossed and dotted the landscape. This and other studies support the theory that there were once oceans, too. But just how much water existed on Mars’ surface, and for how long, is still a matter of much debate.

The new research suggests that the asteroids delivered enough water to early Mars’ surface for a global ocean at least 980 feet (300 meters) deep. In some areas, the ocean could have been up to 0.62 miles (one kilometer) deep. This also includes Mars’ own water supply, outgassing from the planet’s mantle at the time. As the paper explained:

Late delivery of this volatile-rich material to Mars provided an exotic water inventory corresponding to a global water layer >300 meters deep, in addition to the primordial water reservoir from mantle outgassing.

Just how much of the surface water actually covered, however, is still uncertain. Previous research said that an ancient ocean likely covered most of the northern hemisphere in the lowlands. To this day, we can see a distinct boundary between these lowlands and the more rugged, cratered terrain of the southern hemisphere. As Bizzarro explained:

This happened within Mars’s first 100 million years. After this period, something catastrophic happened for potential life on Earth. It is believed that there was a gigantic collision between the Earth and another Mars-sized planet. It was an energetic collision that formed the Earth-moon system and, as the same time, wiped out all potential life on Earth.

Clues from Martian meteorites

So, how did the researchers figure out how much water Mars had a few billion years ago? It was 31 Martian meteorites that provided the valuable clues. Analysis of the meteorites showed that they used to be part of Mars’ original crust, before they were blasted into space by asteroid impacts. The researchers measured the variability of a single chromium isotope (54Cr) in the meteorites. By doing so, the team estimated the impact rate for Mars circa 4.5 billion years ago and how much water the asteroids delivered.

The meteorites provide a window into what Mars’ surface was like within the first 100 million years or so. On Earth, plate tectonics have erased all such evidence. Bizzarro said:

Plate tectonics on Earth erased all evidence of what happened in the first 500 million years of our planet’s history. The plates constantly move and are recycled back and destroyed into the interior of our planet. In contrast, Mars does not have plate tectonics such that planet’s surface preserves a record of the earliest history of the planet.

Overall, the new study support previous research indicating that Mars at one time had an ocean or oceans. It may also have been a good environment for life to start – perhaps even before on Earth – thanks largely to the organic molecules that the asteroids brought as well. The red planet, now cold and dry, was once blue and wet … and, maybe, very much alive.

Bottom line: A new study from researchers in Europe says that Mars once had enough water, largely brought by asteroids, for a deep global ocean. The asteroids also brought organic molecules necessary for life.

Source: Late delivery of exotic chromium to the crust of Mars by water-rich carbonaceous asteroids