Earth to give Lucy spacecraft a boost

The Lucy spacecraft – named for a famous fossilized skeleton found in Africa in 1974 – launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on October 16, 2021. Now, exactly one year later, the spacecraft will swing past Earth for a gravity assist on Sunday, October 16, 2022. During this 2022 gravity assist, Lucy will sweep within 219 miles (352 km) of Earth’s surface! In fact, Lucy will come so close to Earth that some lucky observers located in the right places will get to watch the spacecraft soar overhead. More on who might see it, below.

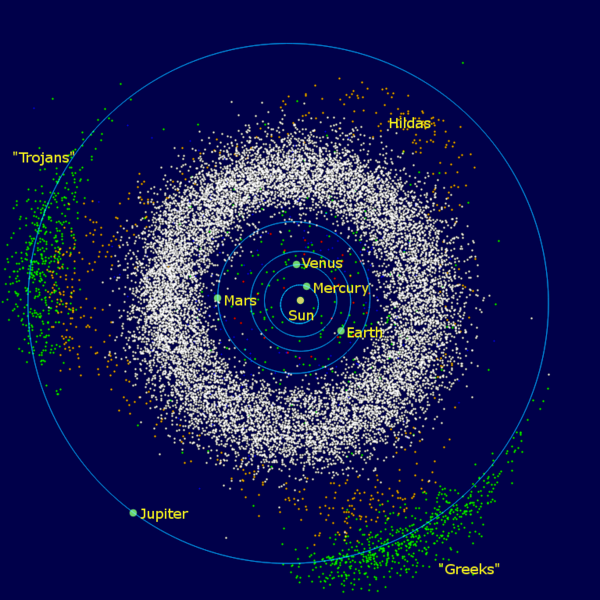

Lucy is on a 4-billion-mile (6-billion-km) journey to explore one main-belt asteroid and seven of Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids.

Sunday’s close pass is the first of three gravity assists from Earth, as the spacecraft winds its way outward through the solar system on its 12-year journey.

Who will see Lucy?

Heads up Western Australia! For you, Lucy will appear to the eye alone as a star moving through the night sky. Then, as Lucy passes over western North America, it will be a bit farther away. So, it will be fainter. But people in western North America can use binoculars to spot Lucy. The SwRI website explained:

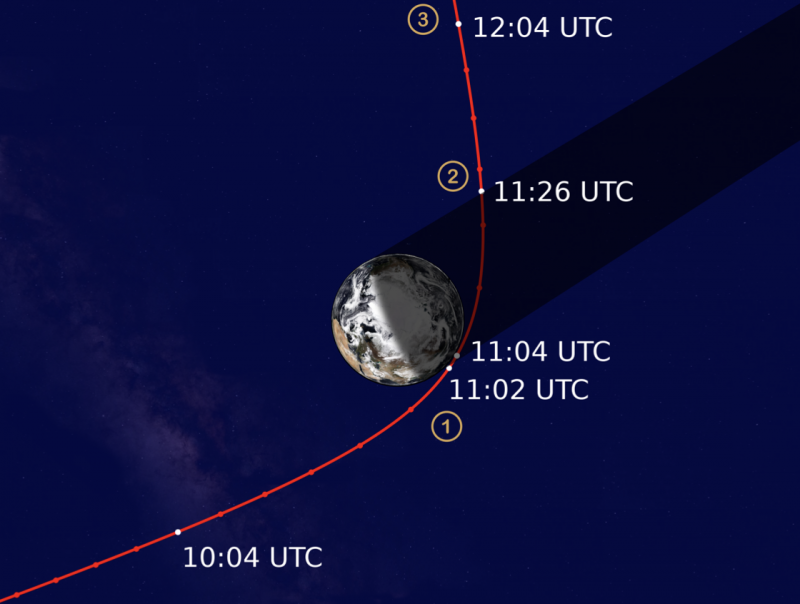

At around 10:55 UTC, 6:55 p.m. local time, Lucy will first be visible to observers on the ground in Western Australia. Lucy will quickly pass overhead, clearly visible to the unaided eye before disappearing at 11:02 UTC (7:02 p.m. local) as the spacecraft passes into the Earth’s shadow.

Lucy will continue over the Pacific Ocean in darkness and emerge from the Earth’s shadow at 4:26 am PT (11:26 UTC). If the clouds cooperate, sky watchers in the western United States should be able to get a view of Lucy with the aid of binoculars.

Check out the maps on this page for more info on how to see Lucy

At closest approach during #EarthGravityAssist, Lucy will be deep into low Earth orbit, below the current altitude of the International Space Station! Stay tuned for info about how you can #SpotTheSpacecraft from Earth if you live in Australia or western North America. pic.twitter.com/7jBU6ZDI2M

— Lucy Mission (@LucyMission) October 7, 2022

Why visit the Trojan asteroids?

Notably, the Trojans move in Jupiter’s orbit around the sun. And, since they’ve never been explored before, scientists view them as fossils left over from the formation of the solar system.

With this in mind, our fossilized ancestor called Lucy dates to some 3.2 million years ago. And the skeleton of the fossil Lucy provided unique insight into human evolution. Likewise, the Lucy space mission will hopefully provide insight into our solar system’s evolution. Astronomer Hal Levison of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado, leads the Lucy mission. He spoke about Lucy’s journey to Jupiter’s Trojans and about how the mission got its name:

The Trojan asteroids are leftovers from the early days of our solar system, effectively fossils of the planet formation process. They hold vital clues to deciphering the history of our solar system. The Lucy spacecraft, like the human ancestor fossil for which it is named, will revolutionize the understanding of our origins.

The Lucy spacecraft’s long journey

Ultimately, Lucy’s 4-billion-mile journey will take it out to the orbit of Jupiter and the realm of Trojan asteroids, then back in toward Earth for gravity assists three times. Indeed, this will be the first time a spacecraft has ever returned to Earth’s vicinity from the outer solar system.

To answer some questions: the Lucy spacecraft is going out to several asteroids that share a very stable orbit around the Sun with the planet Jupiter. These asteroids are not coming to Earth! Follow @AsteroidWatch

for more about how we track asteroids near Earth.— NASA Solar System (@NASASolarSystem) October 16, 2021

The Lucy spacecraft target: Trojan asteroids

To be sure, Trojan asteroids are a unique group of rocky bodies. Left over from the formation of the solar system, they orbit the sun on either side of Jupiter. Until now, no spacecraft has previously explored this collection of solar system fossils. Jupiter’s gravity, in effect, traps these asteroids in two swarms in its orbit, with some ahead of the planet and some trailing behind.

Given these points, deputy principal investigator Cathy Olkin said:

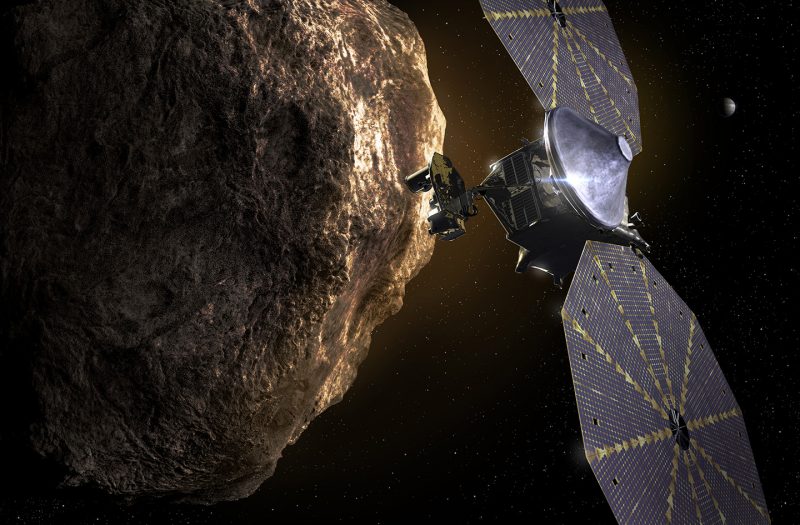

Lucy’s ability to fly by so many targets means that we will not only get the first up-close look at this unexplored population, but we will also be able to study why these asteroids appear so different. The mission will provide an unparalleled glimpse into the formation of our solar system, helping us understand the evolution of the planetary system as a whole.

Bottom line: The Lucy spacecraft launched on October 16, 2021. It’s heading to Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids. On October 16, 2022, the spacecraft will get a gravity assist from Earth.

Read more about the Lucy mission

Check out the maps on this page for more info on how to see Lucy