Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is shrinking

Jupiter is a gas giant planet with an atmosphere that teems with whorls and bands. The most famous feature on Jupiter is its stormy Great Red Spot, which has raged on the planet for hundreds of years. It’s a counterclockwise-moving storm – an anticyclone – with winds as high as 300 miles (480 km) per hour. But the Great Red Spot is shrinking. The storm we see today is smaller and rounder than what observers photographed and sketched in the past.

Why has the Great Red Spot lasted so long? Well, without surface features, the storms on Jupiter don’t encounter friction like on Earth. Anyone who lives by a mountain knows that such features can cause storms to dump rain on one side and then dry up by the time they reach the other side. There are no such influences on Jupiter’s storms, so they rage for decades and centuries.

So, why is the Great Red Spot shrinking? Researchers aren’t sure. You can read more about it here.

The 2024 lunar calendars are here! Best Christmas gifts in the universe! Check ’em out here.

Images of Jupiter’s iconic storm from hundreds of years ago

We don’t know exactly how long people have seen the Great Red Spot. Robert Hooke may have spotted it in 1664. But some people believe he was looking at a different storm. Also, the Great Red Spot we see today may be different from the storm observers saw in the 1600s. Below is a painting from 1711 showing the first depiction of the Great Red Spot as red.

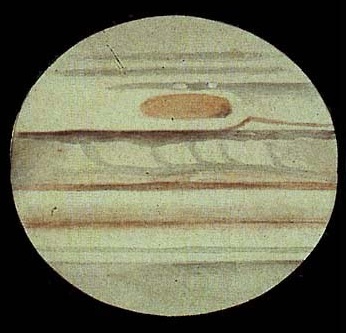

From 1831 to 1879, there are 60 recorded observations of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot. From then on, observers have been continuously monitoring it. Below is a sketch from 1881, showing how large and oblong it was at that time.

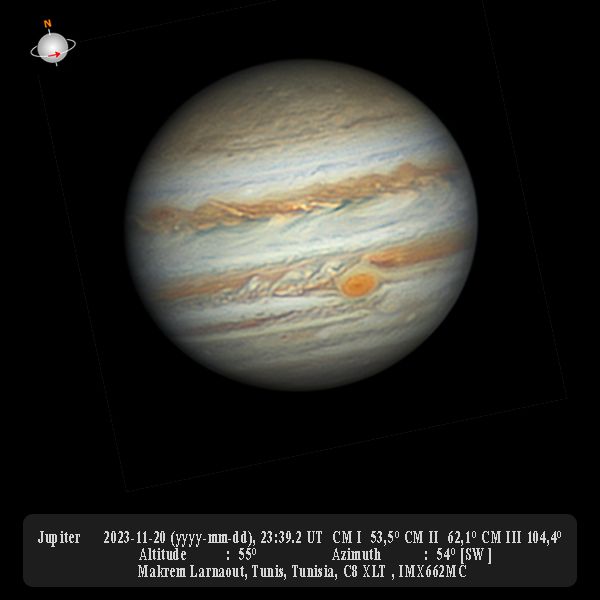

More recent observations

Here are more comparisons of the Great Red Spot – then and now – from photographic evidence. From an observation at Lick Observatory in 1891 (in Damian Peach’s post), to the Pioneer 10 and Voyager flybys of the 1970s, you can see for yourself that the storm has shrunk and taken on a rounder appearance over the years.

The Pioneer 10 images of Jupiter's Great Red Spot in 1973 were dramatic, since the storm was LARGE, and RED, surrounded by whitish clouds. The GRS today is still the largest storm in the Solar system, but it is now a shadow of its former glory. https://t.co/mTkoONz2GS pic.twitter.com/F0gYlZVWLv

— Dr Heidi B. Hammel (@hbhammel) November 24, 2023

Do you have a photo of Jupiter to share? Send it to us!

Bottom line: Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is shrinking! Look at images from the 1800s to now and see how it’s gotten smaller and rounder.